2,900-Year-Old Clay Brick Yields Ancient DNA, Unveiling a Time Capsule of Plant Life

University of Oxford researchers have contributed to the first successful extraction of ancient DNA from a 2,900 year-old clay brick. The analysis, published today in Nature Scientific Reports, provides a fascinating insight into the diversity of plant species cultivated at that time and place, and could open the way to similar studies on clay material from different sites and time periods.

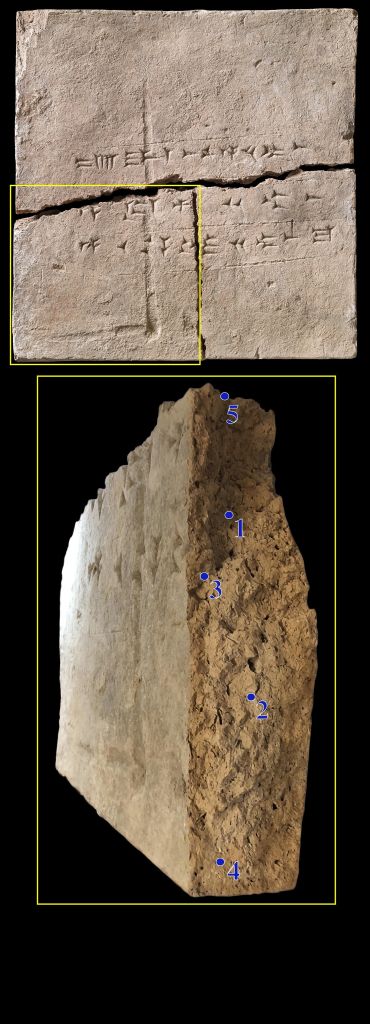

During a digitalization project at the Museum in 2020, the group of researchers were able to obtain samples from the inner core of the brick – meaning that there was a low risk of DNA contamination since the brick was created. The team extracted DNA from the samples by adapting a protocol previously used for other porous materials, such as bone.

After the extracted DNA had been sequenced, the researchers identified 34 distinct taxonomic groups of plants. The plant families with the most abundant sequences were Brassicaceae (cabbage) and Ericaceae (heather). Other represented families were Betulaceae (birch), Lauraceae (laurels), Selineae (umbellifiers), and Triticeae (cultivated grasses).

With the interdisciplinary team comprising assyriologists, archaeologists, biologists, and geneticists, they were able to compare their findings with modern-day botanical records from Iraq as well as ancient Assyrian plant descriptions.

The brick would have been made primarily of mud collected near the local Tigris river, mixed with material such as chaff or straw, or animal dung. It would have been shaped in a mould before being inscribed with cuneiform script, then left in the sun to dry. The fact that the brick was never burned, but left to dry naturally, would have helped to preserve the genetic material trapped within the clay.

Dr Sophie Lund Rasmussen (Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, Department of Biology, University of Oxford), joint first author of the paper, said: ‘We were absolutely thrilled to discover that ancient DNA, effectively protected from contamination inside a mass of clay, can successfully be extracted from a 2,900-year-old brick. This research project is a perfect example of the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in science, as the diverse expertise included in this study provided a holistic approach to the investigation of this material and the results it yielded.’

In addition to the fascinating insight this individual brick revealed, the research serves as a proof of concept and method which could be applied to many other archaeological sources of clay from different places and time periods around the world, to identify past flora and fauna. Clay materials are nearly always present in any archaeological site around the world, and their context means they can often be dated with high precision.

‘Because of the inscription on the brick, we can allocate the clay to a relatively specific period of time in a particular region, which means the brick serves as a biodiversity time-capsule of information regarding a single site and its surroundings. In this case, it provides researchers with a unique access to the ancient Assyrians’ said Dr Troels Arbøll, joint first author of the paper and junior research fellow at the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Oxford, when the study was conducted.

The study ‘Revealing the secrets of a 2900‑year‑old clay brick, discovering a time capsule of ancient DNA’ has been published in Nature Scientific Reports.

The research was conducted in collaboration with Troels Pank Arbøll from Department of Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies, University of Copenhagen; Sophie Lund Rasmussen from the Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, Department of Biology, University of Oxford; Anne Haslund Hansen from Modern History and World Cultures, National Museum of Denmark; Nadieh de Jonge, Cino Pertoldi and Jeppe Lund Nielsen from Department of Chemistry and Bioscience, Aalborg University and Aalborg Zoo (CP).