University of Toronto mourns Indigenous children whose remains were found at former B.C. residential school

The University of Toronto has lowered its flags to half-mast across its three campuses to join the nation in mourning the 215 Indigenous children whose remains were found at the site of a former Indian Residential School in British Columbia.

“The news is absolutely heartbreaking,” U of T President Meric Gertler said in a statement. “It is part of an unconscionable history of injustice against Indigenous peoples in Canada extending from first contact to the present day.”

At a town hall at U of T Mississauga, Vice-President and Principal Alexandra Gillespie observed a moment of silence lasting two minutes and 15 seconds. A moment of silence will also be observed at U of T Scarborough’s Rainbow Tie Gala on June 3.

The Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation said last week that a survey of the grounds at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School uncovered the remains of 215 children buried at the site.

Speaking on behalf of U of T, President Gertler acknowledged in his statement the dignity of each of the 215 children, their families and their communities. He also noted the impact of the news on the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation, other Indigenous communities whose children’s remains are among those discovered, all survivors of Canada’s Indian Residential School system and Indigenous members of the U of T community.

“It comes amidst the continuing trauma inflicted by residential schools as well as ongoing concerns about the disappearance of many Indigenous people across the country,” he said.

Michael White

For Michael White, director of U of T’s First Nations House and Indigenous Student Services, the news of the children’s remains came with a feeling of numbness.

“Members of my family attended residential schools and not all of them survived,” White says. “Within Indigenous communities, we have carried this collective grief for quite some time. We know that there are more: there were unmarked graves and kids who disappeared at all of these schools.”

“These were not really schools. It was incarceration.”

Funded by the Canadian government for more than a century, the Indian Residential School system was a nationwide network of boarding institutions that removed Indigenous children from their families and deprived them of connections to their Indigenous identities while seeking to assimilate them into European culture. Indigenous children in the system were routinely abused.

White has visited the site of St. Joseph’s School for Girls, a residential school in Spanish, Ont., where his grandmother was held from ages four to 16.

The school instilled in her a belief that her Indigenous heritage shouldn’t be celebrated, that she was ‘less-than,’” White says.

“She wasn’t taught subjects like calculus or astronomy,” he says. “She was taught how to be a subservient member of Canadian society.”

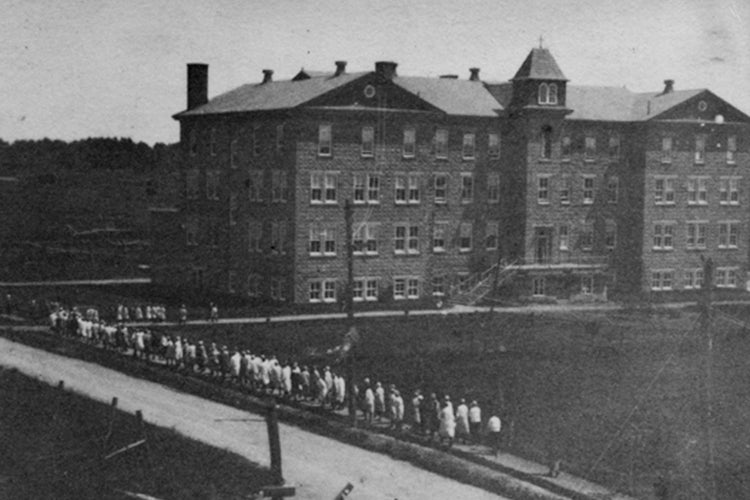

The St. Joseph’s School for Girls in Spanish, Ont. (photo courtesy of Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre)

Indigenous children were brought to the institution on a crowded barge, White notes. Residential schools were intentionally located far from the children’s communities, as a means of dissuading them from attempting to return home.

White plans to one day bring his daughter to the site of the school, where the shell of the building still stands some decades after it was ravaged by fire.

“I’m going to take her there and explain to her what it means to be Anishinaabe,” he says.

In his statement, President Gertler points out U of T’s continued implementation of the Calls to Action in Wecheehetowin: Answering the Call, the report of the university Steering Committee in response to Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s calls to action, which seek to redress the legacy of residential schools.

Shannon Simpson

“U of T has made a commitment to moving forward with the specific calls to action,” says Shannon Simpson, U of T’s director of Indigenous Initiatives. “There is still a lot of work to be done, but we are on our way.

“I think we’ll get there.”

For Indigenous students who may require support at this time, U of T’s First Nations House is hosting Sharing Circles on Zoom this week with James Carpenter, an Anishnaabe knowledge keeper and healer.

Counselling appointments with Honarine Scott and other wellness counsellors are available to students at First Nations House.

Students can also access supports through Indigenous student services, while U of T My Student Support Program (SSP) offers students 24-hour confidential support that can be accessed over the phone in 35 languages, while support scheduled in advance is available in 146 languages.

Staff and faculty can access the Employee and Family Assistance Program and Simpson says a sharing circle is being planned for staff and faculty across the three campuses.

“Students, staff and faculty may have different ways they access grief,” she says. “In situations like this, we need to make sure everyone is supported.”