After pandemic hiatus, Native American language survival workshop returns to campus

In the mid-1990s, Quirina Geary was a cashier at a Safeway store in Madera, California, and a young mother of two. While raised in a tribal community in California’s Central Valley, she did not speak her ancestral Mutsun language and wanted to fix that.

Intimidated, yet determined, she headed along with her sister, Clara Luna, to UC Berkeley to attend Breath of Life, a biennial workshop in which California Native Americans pair up with linguists and other scholars to revitalize Indigenous languages by sharing personal histories, knowledge and archival materials.

There, Geary partnered with Natasha Warner, then a Berkeley graduate student in linguistics. The two went on to co-author an English-Mutsun dictionary, among other publications. Mutsun is one of the primary languages of the Tamien Nation and other tribes whose respective homelands extend from South San Francisco to Monterey Bay and San Benito County. Ascención Solórsano, the last first-language Mutsun speaker, died in 1930.

“Coming from a rural community with only a high school diploma, we never would have stepped foot in a university,” recalled Geary. “But when we got to Berkeley, the archivists and everybody there made us feel OK.”

Better than OK.

“If not for Breath of Life, there would be no Mutsun dictionary,” she added. “We would not be learning our language.”

Breath of Life returns

This Sunday, May 22, marks the in-person return of Breath of Life to the Berkeley campus. Now in its 27th year, it was last held at Berkeley in 2018. It moved online in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Geary (left) and Leanne Hinton at the 2016 Breath of Life conference at Berkeley. (Photo by Scott Braley)

Running through May 28, the event is sponsored by Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival (AICLS) and Berkeley’s linguistics department. More than 90 people are expected to attend, including Geary, who is an AICLS board member and chair of the Santa Clara Tamien Nation.

Berkeley linguistics Professor Emerita Leanne Hinton, who co-founded AICLS in 1992 and Breath of Life three years later, looks forward to meeting members of the Indigenous language revitalization community face to face after a four-year hiatus.

“While AICLS and campus archivists did what they could to bring people together with their languages virtually during those first COVID years, we are so looking forward to getting together again in person for the first time since 2018,” Hinton said.

The Native languages represented at the conference will include Chemehuevi, Central Sierra Miwok, Chochenyo, Concow Maidu, Eastern Pomo, Karuk, Lake Miwok, Northern Miwok, Mutsun, Nisenan, Nomlaki, Northern Paiute, Northern Pomo, Patwin, Pacific Coast Athabaskan, Ramaytush, Rumsen, Southern Sierra Miwok, Tachi, Tamien, Tiłhini, Tongva, Washoe and Western Mono.

Their survival is remarkable, given California’s colonial history.

Post-colonial rebirth

Before Spanish colonization and the founding of Mission San Diego in 1769, some 90 Indigenous languages and 300 dialects were spoken across what is now California. Thereafter, many tribes were decimated, and over generations, fewer members spoke their language.

In recent decades, however, there’s been a revival of Indigenous language and culture, thanks in no small part to the determination of tribal communities and such resources as Berkeley’s Bancroft Library and Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, along with the Survey of California and Other Indian Languages, a Berkeley research center that houses the California Language Archive, one of North America’s largest collections of Indigenous language materials.

“Getting to learn an ancestral language from documents and recordings that might have been made by your grandparents and your great-grandparents can be rewarding, not just for California Native Americans, but also for archivists and linguists who contribute their time to work with Indigenous language teams,” said Berkeley linguistics professor Andrew Garrett, director of the Survey of California and Other Indian Languages.

“It’s this kind of community engagement that makes working at Berkeley so meaningful,” he added.

Zachary O’Hagan, manager of the California Language Archive, stands among the collections in Dwinelle Hall (UC Berkeley photo by Yasmin Anwar)

At Breath of Life, attendees will have access to audio recordings on tape and wax cylinders, field notes and other linguistic materials and artifacts at Berkeley. For their final project, they can recite poems or prayers, sing songs or perform skits with the words they learn in their ancestral languages.

“People may not learn a language fluently, but they can get a strong sense of connection by coming together for certain rituals that are conducted in their ancestral language,” said Zachary O’Hagan, manager of the California Language Archive and a Berkeley alumnus with a Ph.D. in linguistics.

A California Native American homecoming

That linguistic connection is what Geary yearned for when she and Clara Luna ventured north to their first Breath of Life workshop after finding a flyer about it at a local language revitalization event.

They sought to remedy the cultural alienation they felt as children who spoke no words in their tribal language.

“A lot of people want to learn more about their tribal language and culture when they have children,” she said. “They want to pass something down to them that they didn’t have, and that was part of my drive.”

It wasn’t until they started attending Breath of Life that they were able to piece together their linguistic history.

For example, they learned that Josefa Velásquez, their great-great-great-grandmother, had worked with scholars in the early 1900s to preserve the Mutsun language.

As fate would have it, the sisters’ assigned mentor in 1997 did not show up, so they teamed up with Warner, then a Berkeley graduate student in linguistics who was also keen to learn Mutsun.

“We finally had somebody with some linguistic background to help us understand the materials that we were finding,” Geary recalled.

After the conference, she kept up a decades-long correspondence with Warner, by then a linguistics professor at the University of Arizona. It culminated in them co-authoring an English-Mutsun dictionary that was published online in 2016.

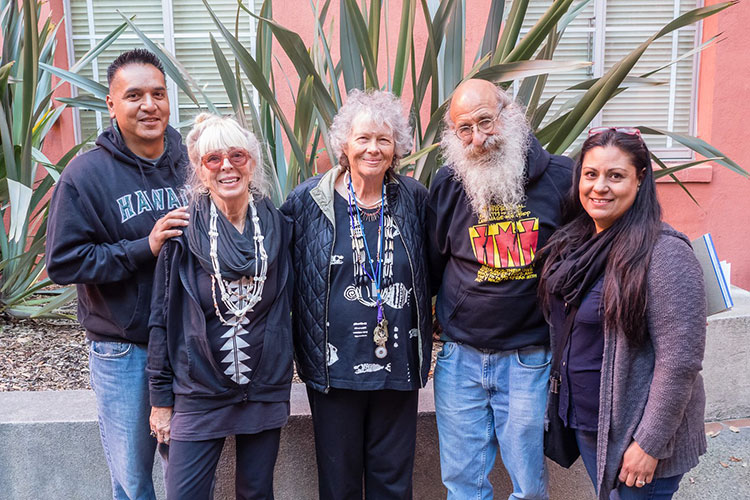

Robert Geary (far left), Marina Drummer, Leanne Hinton, Malcolm Margolin and Quirina Geary at the 2016 Breath of Life workshop. (Photo by Scott Braley)

Meanwhile, Geary became a leader in the Santa Clara Tamien Nation, a UC Davis linguistics scholar and a staunch advocate for Native language revitalization. She also teaches Mutsun and writes children’s books. Her husband, Robert Geary, belongs to the Elem Indian Colony Reservation of Pomo Indians in Lake County, California, where the couple lives. Between them, they have 10 children, who range in age from 11 to 30.

Her schedule is demanding, but she’s not too busy to attend next week’s Breath of Life workshop. After all, that’s where it began.

“This program has really made a difference — not just for me personally, but for us as an Indigenous community that has been scattered and broken since our lands were taken from us,” Geary said.

“When you go to Breath of Life, especially as a first-timer, you’re going to cry with emotion at some point, because you’re finding out that your own grandmother or great-grandmother left some information that contributed to the survival of your language, a language that you can bring back to life.”