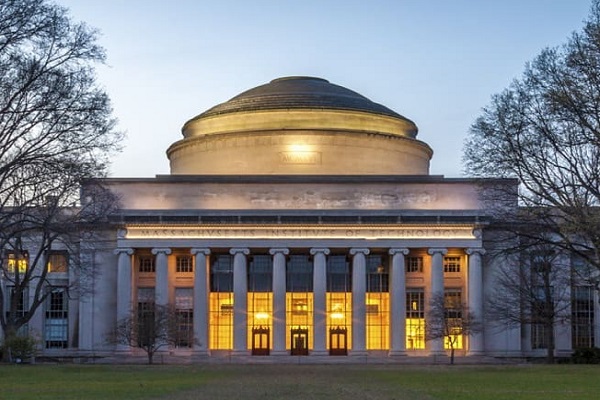

Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Researchers discover a new hardware vulnerability in the Apple M1 chip

William Shakespeare might have been talking about Apple’s recently released M1 chip via his prose in “A Midnight Summer’s Dream”: “And though she be but little, she is fierce.”

The company’s software runs on the little squares made of custom silicon systems, resulting in Apple’s most powerful chip to date, with industry-leading power efficiency.

Yet despite the chip’s potency, there’s been no shortage of vulnerability grievances, as fears of sensitive data and personal information leaks abound. More recently, the chip was found to have a security flaw that was quickly deemed harmless.

The M1 chip uses a feature called pointer authentication, which acts as a last line of defense against typical software vulnerabilities. With pointer authentication enabled, bugs that could normally compromise a system or leak private information are stopped dead in their tracks.

Now, researchers from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) have found a crack: Their novel hardware attack, called PACMAN, shows that pointer authentication can be defeated without even leaving a trace. Moreover, PACMAN utilizes a hardware mechanism, so no software patch can ever fix it.

A pointer authentication code, or PAC for short, is a signature that confirms that the state of the program hasn’t been changed maliciously. Enter the PACMAN attack. The team showed that it’s possible to guess a value for the PAC, and reveal whether the guess was correct or not via a hardware side channel. Since there are only so many possible values for the PAC, they found that it’s possible to try them all to find the correct one. Most importantly, since the guesses all happen under speculative execution, the attack leaves no trace.

“The idea behind pointer authentication is that if all else has failed, you still can rely on it to prevent attackers from gaining control of your system. We’ve shown that pointer authentication as a last line of defense isn’t as absolute as we once thought it was,” says Joseph Ravichandran, an MIT graduate student in electrical engineering and computer science, CSAIL affiliate, and co-lead author of a new paper about PACMAN. “When pointer authentication was introduced, a whole category of bugs suddenly became a lot harder to use for attacks. With PACMAN making these bugs more serious, the overall attack surface could be a lot larger.”

Traditionally, hardware and software attacks have lived somewhat separate lives; people see software bugs as software bugs and hardware bugs as hardware bugs. Architecturally visible software threats include things like malicious phishing attempts, malware, denial-of-service, and the like. On the hardware side, security flaws like the much-talked-about Spectre and Meltdown bugs of 2018 manipulate microarchitectural structures to steal data from computers.

The MIT team wanted to see what combining the two might achieve — taking something from the software security world, and breaking a mitigation (a feature that’s designed to protect software), using hardware attacks. “That’s the heart of what PACMAN represents — a new way of thinking about how threat models converge in the Spectre era,” says Ravichandran.

PACMAN isn’t a magic bypass for all security on the M1 chip. PACMAN can only take an existing bug that pointer authentication protects against, and unleash that bug’s true potential for use in an attack by finding the correct PAC. There’s no cause for immediate alarm, the scientists say, as PACMAN cannot compromise a system without an existing software bug.

Pointer authentication is primarily used to protect the core operating system kernel, the most privileged part of the system. An attacker who gains control of the kernel can do whatever they’d like on a device. The team showed that the PACMAN attack even works against the kernel, which has “massive implications for future security work on all ARM systems with pointer authentication enabled,” says Ravichandran. “Future CPU designers should take care to consider this attack when building the secure systems of tomorrow. Developers should take care to not solely rely on pointer authentication to protect their software.”

“Software vulnerabilities have existed for roughly 30 years now. Researchers have come up with ways to mitigate them using various innovative techniques such as ARM pointer authentication, which we are attacking now,” says Mengjia Yan, the Homer A. Burnell Career Development Professor, assistant professor in the MIT Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS), CSAIL affiliate, and senior author on the team’s paper. “Our work provides insight into how software vulnerabilities that continue to exist as important mitigation methods can be bypassed via hardware attacks. It’s a new way to look at this very long-lasting security threat model. Many other mitigation mechanisms exist that are not well studied under this new compounding threat model, so we consider the PACMAN attack as a starting point. We hope PACMAN can inspire more work in this research direction in the community.”