Unmasking Urban Bats: Audio Recordings Aid in Identifying Not-So-Spooky Sounds

Living along the Mississippi Flyway, as we do, St. Louis residents are accustomed to hearing and seeing thousands of ducks, geese and songbirds winging their way over the area twice a year. In the fall, many birds are heading south to warmer climates.

A lesser-known migration is also happening: some Missouri bats are on the move.

Local species such as the silver-haired bat, eastern red bat, hoary bat and evening bat move south in the fall and north in the spring, sometimes flying great distances and in rather large numbers. Others stay in Missouri and hibernate.

In recent years, Washington University in St. Louis researchers working with the St. Louis Wildlife Project have started using acoustic recorders at their wildlife monitoring stations to detect bats for the first time.

“We just completed our fifth year of monitoring wildlife in local green spaces for the St. Louis Wildlife Project,” said Solny Adalsteinsson, a staff scientist at Tyson Research Center, Washington University’s environmental field station.

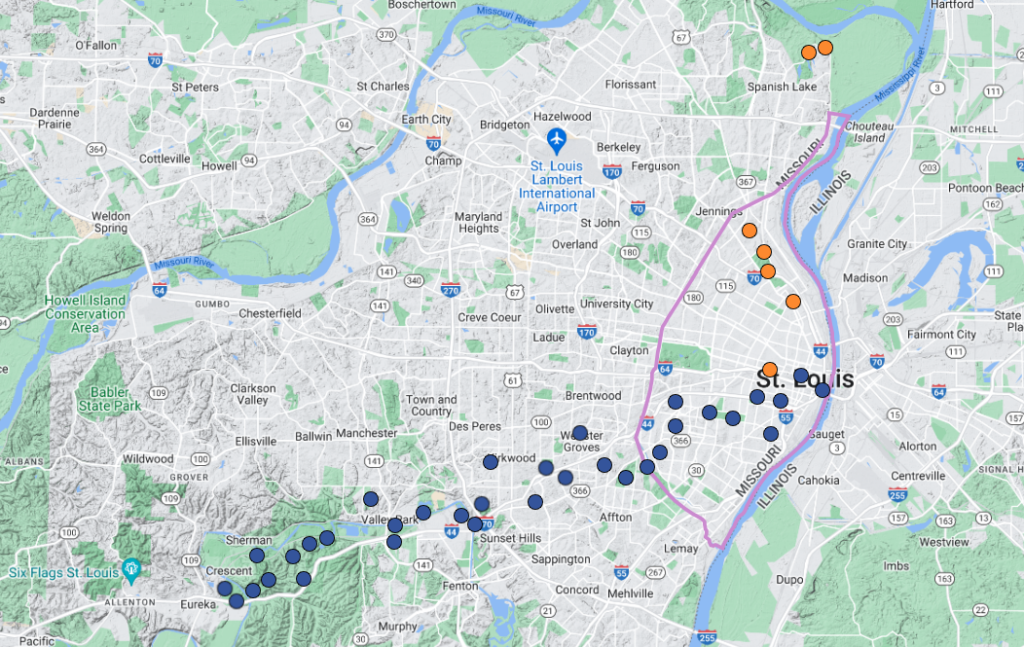

For most of their animal-identifying efforts, the researchers have relied on data collected using motion-activated camera traps set up in city, county, state and national parks, as well as on private lands. Detecting bats via audio recordings is new, and the team has also added monitoring locations along a north-south transect, including at Peace Park, Harris-Stowe State University and Cavalry and Bellefontaine cemeteries. This year, the researchers started collecting recordings at the 425-acre Saint Louis Zoo WildCare Park in north St. Louis County. “We have expanded our bat monitoring quite a bit,” Adalsteinsson said.

Starting in 2021, the scientists began experimenting with recording bird songs and bat calls, in addition to their standard photo identification methods. They deployed a network of Audiomoth acoustic monitors on or adjacent to trees where they had previously installed camera traps to capture images of other wildlife.

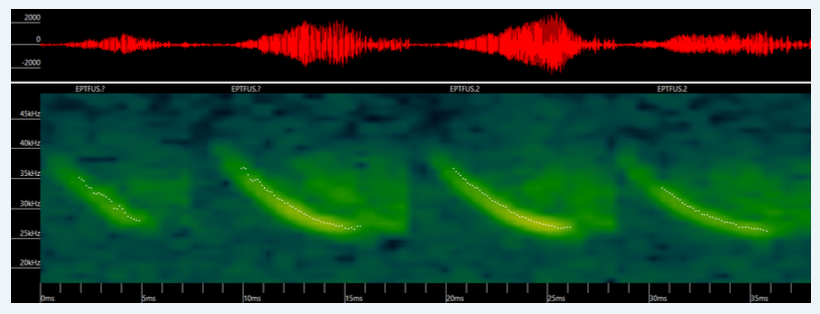

“We’re using these little devices to record sound at the frequency of a bat call, which is higher than what humans can hear,” said Erin O’Connell, research and conservation project coordinator at Tyson Research Center.

“When we’re identifying bats, we’re not necessarily listening to the calls — although, if you slow it down 10 times, then you can hear it,” O’Connell said. “Instead, we are looking at a sonogram and visualizing the sound.” She uses a software tool to compare her St. Louis bat recordings to a digital library of bat calls.

“This allows us to process thousands of files relatively quickly and get the big picture of what species are there,” O’Connell said. The Tyson team is in close communication with partners at the Missouri Department of Conservation and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service — bat experts who are keenly interested in their findings.

The scientists detected 10 total species of bats at their monitoring stations in the greater St. Louis area, including several species of threatened and endangered bats, like a northern long-eared myotis (Myotis septentrionalis). As of March 2023, this kind of bat is now listed as endangered.

The most commonly detected bats were big brown bats and hoary bats.

“Bats are abundant in urban spaces, but the ecology of urban bats is often overlooked,” Adalsteinsson said. “Bats are often viewed as pests, despite the critical role they play in ecosystem functioning.”

Bats serve as insect predators, nutrient recyclers, pollinators and seed dispersers. However, bats are in decline across North America due to a variety of threats, including land use changes, pesticides, disease and climate change.

Adalsteinsson, O’Connell and their collaborators, including Elizabeth Biro at Tyson and Whitney Anthonysamy at the University of Health Sciences and Pharmacy in St. Louis, hope that their work will help support bat conservation by improving understanding of bat habitat use across the local urbanization gradient.

If researchers can determine which habitats bats use seasonally and during different life cycle stages, they and their partners can better target restoration efforts. That might mean creating or restoring bat foraging habitat in urban areas or protecting certain important roosting features.

Including bats, the St. Louis Wildlife Project has identified more than 40 species of animals in local parks and green spaces. Most of these species are identified in photos collected by camera traps in parks. With help from undergraduate students, high school students and other local volunteers, the team has collected and analyzed more than 266,000 photos over the last five years, including those that represent at least 20,000 local animal detections. These observations contribute to ongoing research, including a recent study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution showing the effects of climate, urbanization and species traits on wildlife in cities.