Exploring UCSF Archives: Unveiling the ‘Priceless’ Treasures Within

What turned out to be an old, tattered photo album contained hundreds of images from the early 20th century, most showing doctors, nurses, patients and forgotten buildings of what was then called the Affiliated Colleges.

These days, it’s better known as UC San Francisco.

Like many before it, the album was donated to UCSF and made its way to the UCSF Kalmanovitz Library. Its final destination is ultimately up to Polina Ilieva, UCSF Archivist and Associate University Librarian for Collections. In Ilieva and her team’s care, the photo album will join an impressive collection that spans 150 years’ worth of UCSF history and beyond – centuries beyond, in fact.

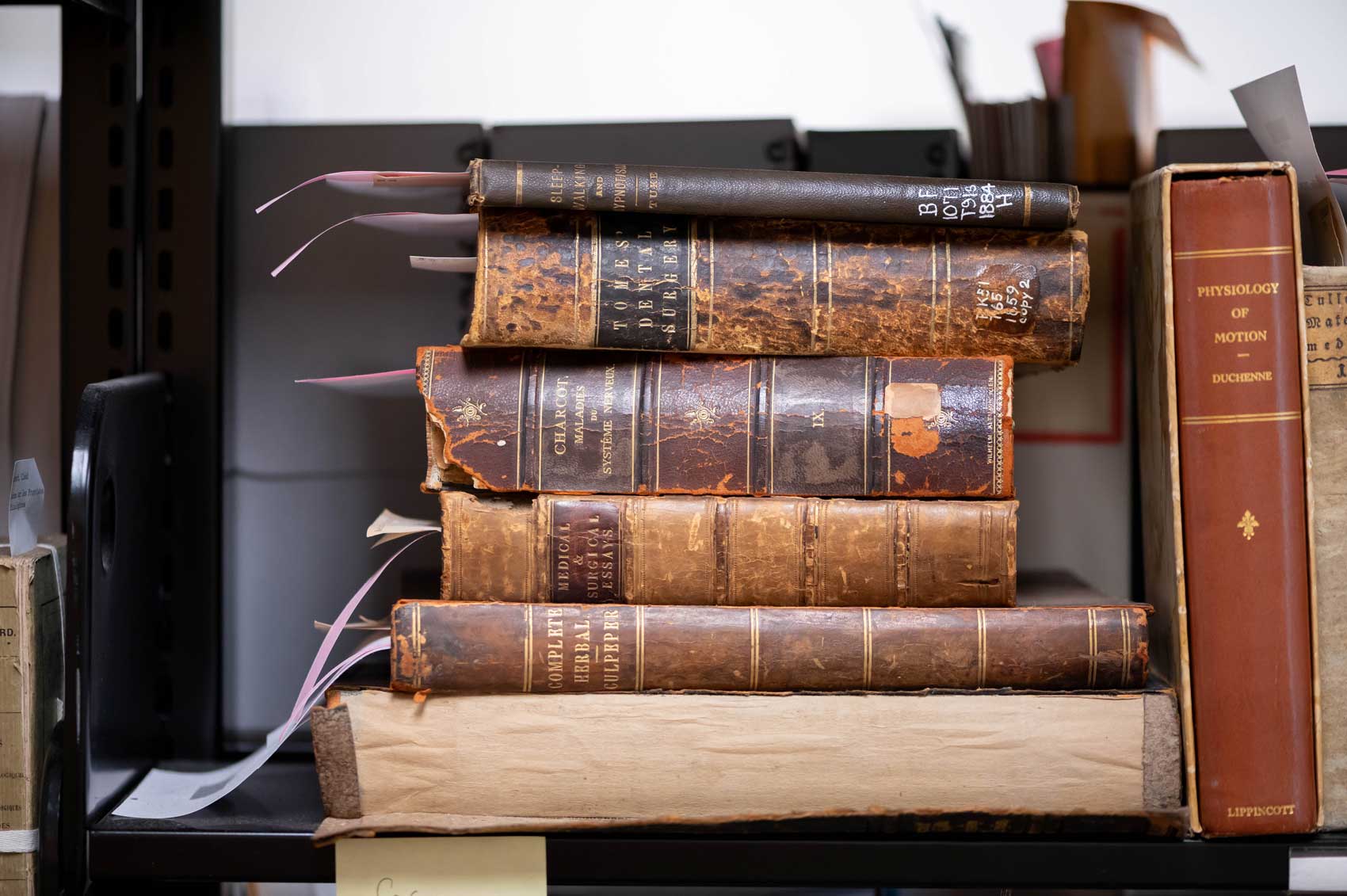

To see the UCSF Rare Book Collection at Parnassus Heights is a fascinating trip through the pages of history. An incredible 21,103 books line neatly organized shelves that sit next to antique medical equipment, war-era nursing uniforms and the largest collection of Japanese woodblock prints related to health found anywhere in the United States. The 400 prints were acquired as part of a UCSF initiative to learn more about East Asian medical practices beginning in the mid-1960s, a project led by the University’s first chancellor, John B. de C.M. Saunders. Most of the other items in the Archives and Special Collections were donated, either by staff, faculty or someone who knew the rare health sciences pieces they had in storage needed a good home.

UCSF Archivist and Associate University Librarian for Collections Polina Ilieva often refers to rare books that are hundreds of years old in the Archives & Special Collections department in the Kalamanovitz Library at the Parnassus campus.

An enormous collection

The room has a distinct smell that comes with having preserved hundreds of years of materials. This isn’t the kind of trove a curious mind goes poking through without first washing hands or putting on gloves in an effort to preserve the artifacts for future generations.

“It’s been a common practice for centuries for doctors to collect books,” Ilieva said as she walked through the collection. “Many of them had big collections. Most of what you see here was actually donated. Previously, the library had a purchasing budget for rare book collecting. Whatever books are coming now are all donations.”

There are thousands more items, too, in off-site East Bay warehouses straight out of a Hollywood blockbuster. In these warehouses owned by the University of California, an astonishing 8,000 linear feet of papers, photos and other materials that no longer fit in UCSF facilities are housed with similar overflow collections owned by UC Davis, UC Berkeley, UC Merced and UC Santa Cruz.

Like the rare books collection, the 886 collections owned by UCSF kept in Richmond are often requested by researchers, filmmakers, students and alumni for various projects and papers. The collections are packed tight and shipped to Parnassus Heights where they’re studied in the Archives and Special Collections Reading Room on the fifth floor of the Kalmanovitz Library.

“It’s been a common practice for centuries for doctors to collect books.”

POLINA ILIEVA, UCSF LIBRARY

Canes, glass eyes and wartime equipment

If that’s where the action is, the real magic lies in the extraordinary items that give the UCSF Rare Book Collection its moniker – and it’s not just limited to books.

It starts with UCSF’s notable collection of posters, fliers and handouts on the history of HIV/AIDS, the most requested material in the archives. “That collection started in 1987,” Ilieva said. “It was joint project of archivists, clinicians, health care providers and community advocates here in San Francisco. That collection has been growing and we have been getting donations of materials almost every month. It has more than 60 distinct collections within that project.”

There’s a collection of wooden canes, owned and used by various UCSF faculty over the years. The cane that will garner the most attention, however, is a gold-headed cane passed down by UCSF students in the Department of Medicine for over two decades. The cane – long a symbol in English medicine – is passed annually to a deserving student who exemplifies the qualities of a “true physician.” This one was refurbished by The Makers Lab, located on the main floor of the library.

It’s no wonder UCSF faculty are well represented in the archives, which was formally established in 1963. The rare book collection itself was started with the founding of Toland Medical College in 1864. It’s here where faculty portraits, many of which are stacked carefully in the back of the archives and commissioned during the faculty member’s time at UCSF, can be found. Some are still making their way to the collection as schools move or upgrade spaces.

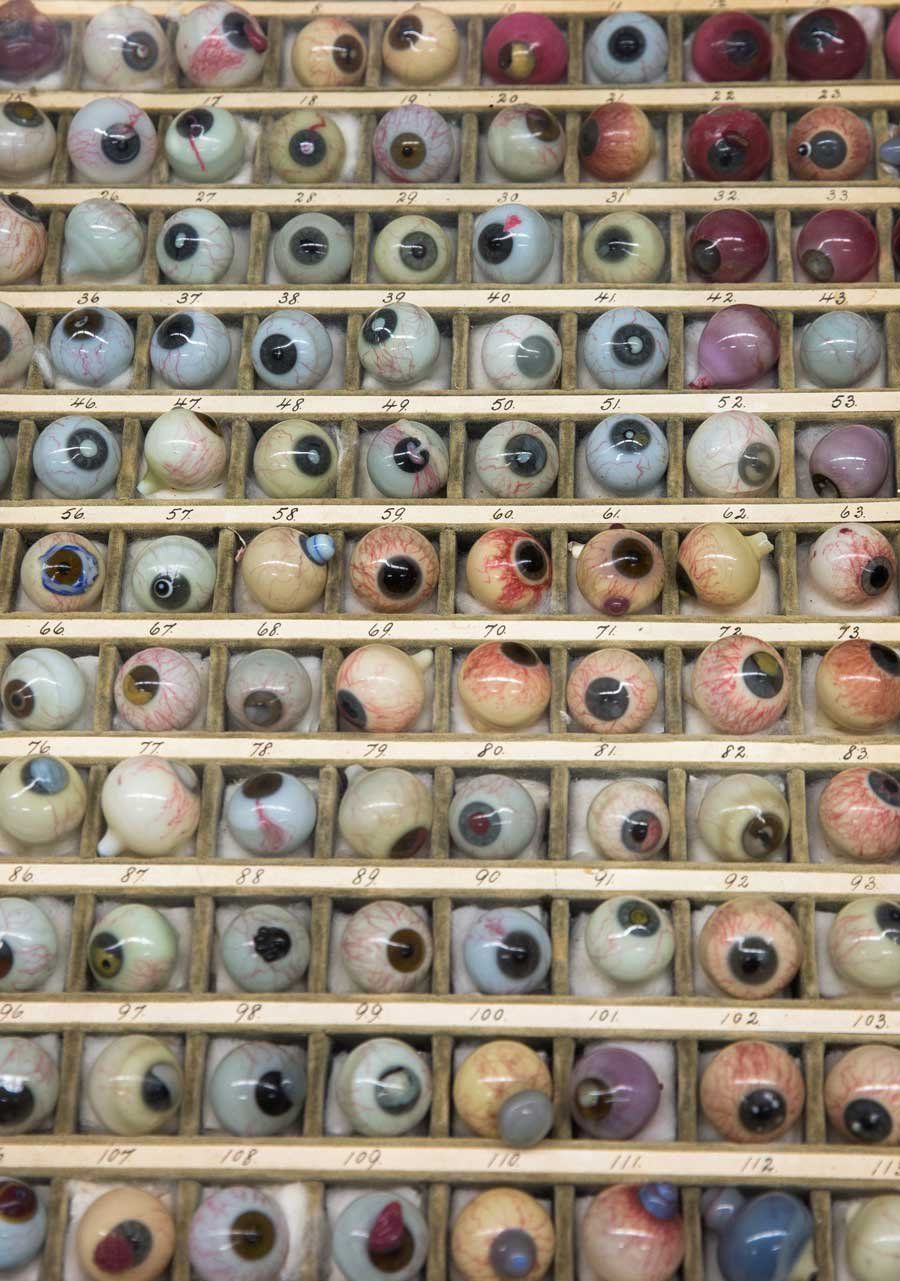

One of the more eye-catching finds is a collection of handblown glass eyeballs, found in a case neatly tucked inside a drawer. “It’s a collection that everyone loves,” Ilieva said.

It’s hard not to. The eyeballs, donated by a family of German immigrants to UCSF, were once used for teaching purposes for a variety of retinal injuries during the Industrial Revolution. “That family, through a great grandson, continues working with UCSF on ocular prosthetics. They now make them out of modern materials.”

Naturally, archives staff has displayed the eyeballs during the Halloween season.

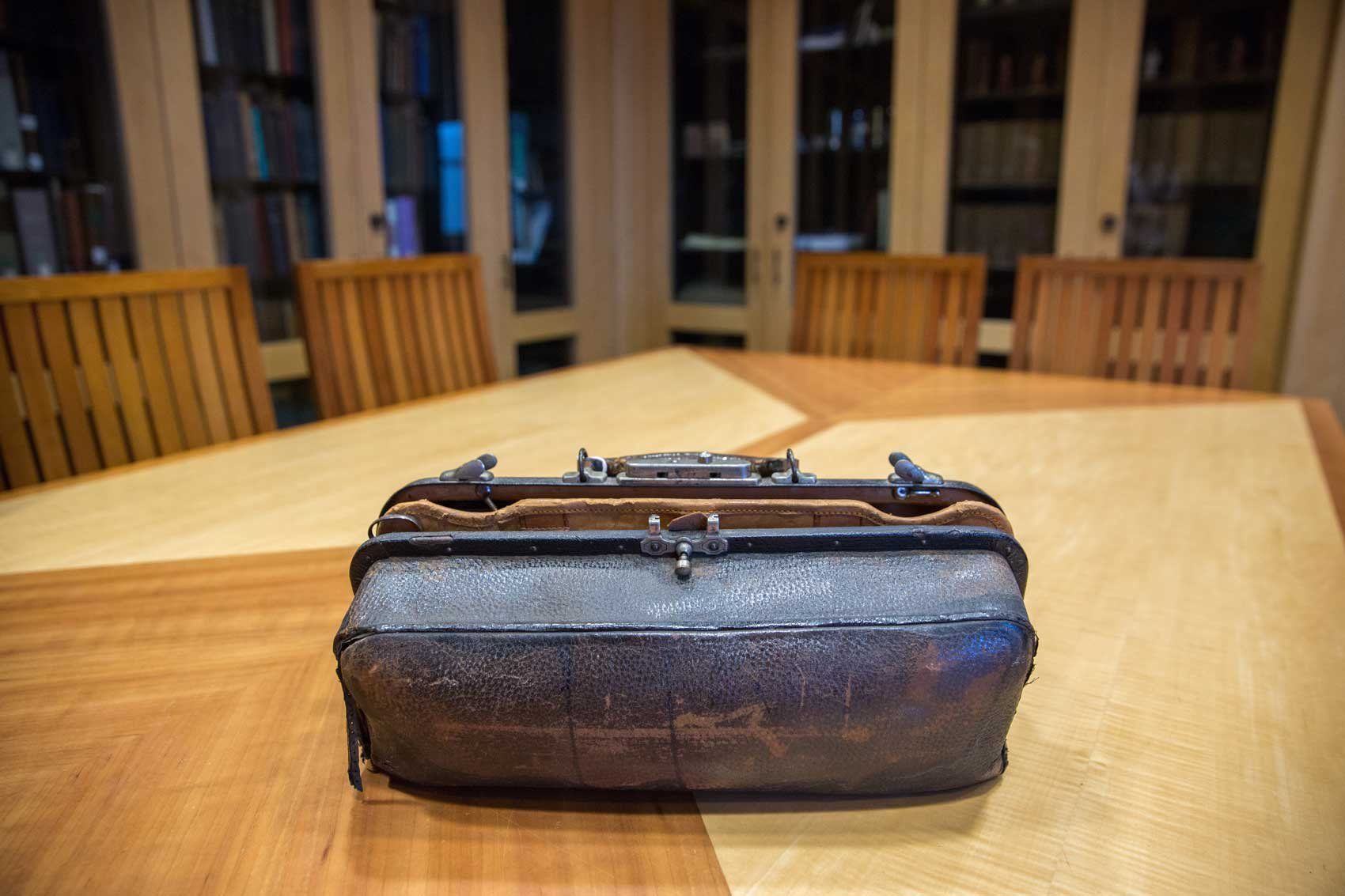

The collection also holds old doctor’s bags (some dating back decades) and antique homeopathy kits, one of which belonged to a “Florence Nightingale Ward” (no relation). It still contains pills marked for an “acute cold,” “dry cough,” “nervousness” and “stomach issues” relating to pain caused by bad oysters. Next to the kit, there’s a portable anesthesia machine and a trachea kit used in service during World War II. The archives are also home to endless file folders and cabinets full of images – everything from aerial shots of UCSF campuses to class composites.

For more recent history, UCSF’s collection also includes the “Mission Bay” headpiece that appeared in productions of the beloved San Francisco stage show “Beach Blanket Babylon.” The show ended in 2019. The hat features new buildings at the Mission Bay campus, among other city landmarks.

Oculist Phil Danz donated this collection of blown glass eye pathological specimens, made in the 1880s by his uncle, Amandus Mueller, to the School of Medicine.

The ‘Tinies’

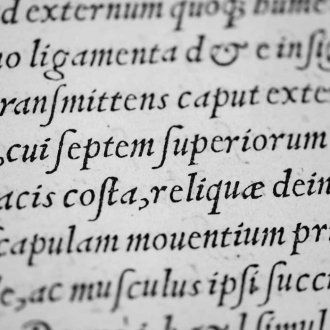

But the real stars of UCSF’s collection are the books themselves, of which there are a lot. UCSF has volumes and volumes that are part of the aforementioned East Asian collection and even a whole section of tiny books, appropriately labeled, “The Tinies.” These miniature books cover topics from reproduction to women’s health, coming into fashion with the advent of the printing press and made to fit snug into the owner’s pocket, according to Ilieva. Some even have notes in the margins from years of differing owners. Most are actually written in Latin, due to their incredibly old age. These books date back to 1477, 1492, 1501 and 1547 stand side-by-side on one shelf alone.

“These [books] would have been more for personal consumption,” Ilieva explained. “The majority of scientific books, books on health sciences [and] medicine…they were much bigger so a lecturer can use a book to teach students.”

Those bigger books are found just around the corner.

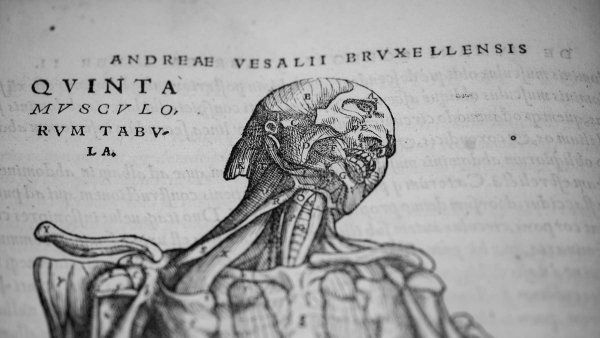

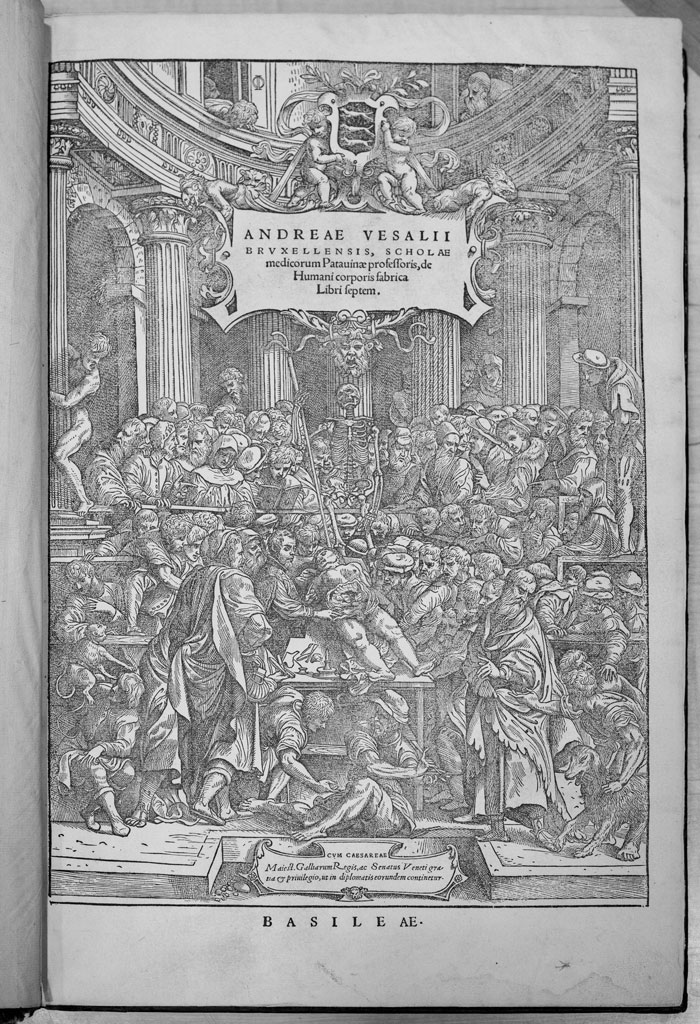

The highlight is “De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem (On the Fabric of the Human Body in Seven Books)” by Andreas Vesalius that Ilieva called “priceless.” The book, published in 1543, is considered the landmark text of modern human anatomy. “The library has the first and second editions,” she said. “Chauncey D. Leake, professor of pharmacology and Herbert McLean Evans, professor of anatomy exchanged first and second edition copies and eventually gifted them to the archives.” Thought to be a “revolutionary” work, the book is famous for its full-scale skeletons and was the first to accurately show details of organs, blood vessels and nerves. Its ideas were so precise that scientists and researchers used it for 300 years following its publication.

“De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem (On the Fabric of the Human Body in Seven Books)” by Andreas Vesalius, published in 1543.

UCSF has others just like it, too. Too many to list here.

The environment is essential for preserving these historical works. For now, temperatures are kept in the low 60s with an attentive eye on humidity. But the current vault has been prone to leaks over the years, with many unwelcome water intrusions from the roof and walls springing up in the middle of recent heavy rains. That’s why a new climate-controlled storage vault is on the way. The vault will feature optimal lighting, chillers, a fire suppression system, and temperature and humidity controls.

The project is on track to be completed in late 2023.

Once done, the new vault will protect priceless books, equipment, uniforms and maybe a yet undiscovered photo album that will eventually find its way home to UCSF.

Outside of physical holdings, the Archives and Special Collections team has been rapidly digitizing its collections in making them publicly accessible online.