Chromosomal DNA Study of Nuclear Test Veterans Reveals No Evidence of Historical Radiation Exposure

Army, RAF and Royal Navy veterans who had been present when British nuclear weapons were tested in the 1950s and 60s have similar levels of changes to their chromosomal DNA as other veterans of the same age, a study has found.

This means that there is no chromosomal evidence of historical radiation exposure in the British nuclear test veterans who took part in the study.

The scientists behind this research, published today in the Journal of Radiological Protection, conclude that the results should offer reassurance to veterans that attendance at nuclear test sites was not, by itself, associated with detectable levels of exposure to radiation.

When nuclear weapons are tested, such as took place in the South Pacific and the Australian outback six decades ago, radiation disperses into the environment or through fallout. This can lead to exposure from external sources or from internalised sources, such as if radioactive particles enter the body through breathing or food – each contributing to the radiation exposure a person receives over their lifetime.

“About a fifth of military men at or near the test sites were, back then, supplied with film badges to measure their external radiation exposure,” said study lead Dr Rhona Anderson from Brunel University London. “Estimates from those readings suggest any exposure would be limited for the majority of personnel, but there are no measurements on record for internalised exposure.”

Nowadays, there are techniques which can look for evidence from chromosomes – the pairs of DNA molecules containing our genetic information. “DNA damage builds up throughout our lives, both naturally and because of medical procedures, perhaps through job-related exposures, and so on,” Dr Anderson said. “But if we compare the amount of damage the nuclear test veterans have to their chromosomal DNA – the lifetime of all their exposures – with the damage of a matched group of veterans of similar age and military service who hadn’t been at test sites, then we will be able to see whether or not there’s a difference between the groups.”

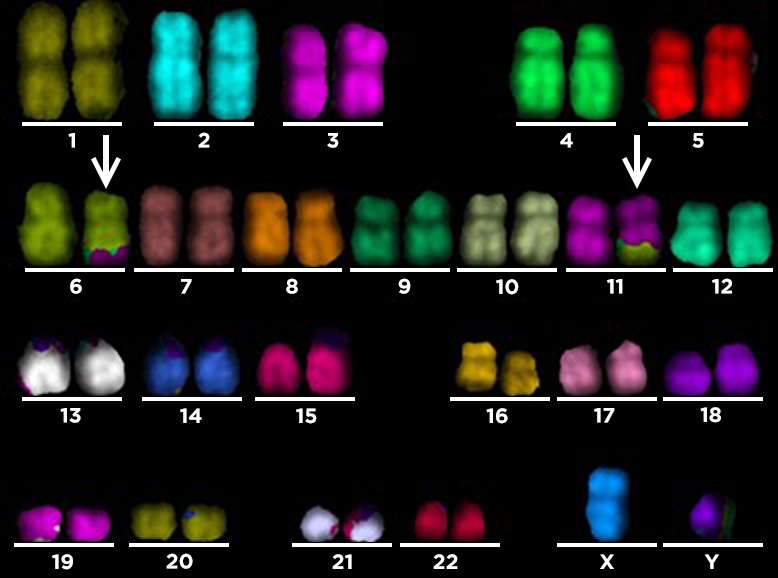

As part of the Genetic and Cytogenetic Family Trio study, supported by the Nuclear Community Charity Fund (NCCF), Dr Anderson and colleagues analysed blood samples from 48 nuclear test veterans and 38 control veterans and then ‘painted’ individual chromosomes using a technique called M-FISH. Under a fluorescence microscope, painted chromosomes appear in a rainbow of colours, making it easy to spot and count up the number of aberrations: instances of damage, such as when building blocks of chromosomal DNA swap places or are deleted. This includes more complex aberrations which are generally thought to happen rarely for most people, but could reveal exposure to low doses of high linear energy transfer radiation – a type of radiation that could be a sign of nuclear weapons tests.

Chromosomes painted using the M-FISH technique, revealing where building blocks of chromosomal DNA have swapped places. Image © Brunel University London

All the samples were processed blind, so the researchers didn’t know which group the blood was from. Once the M-FISH analysis had finished, the samples were revealed as being part of the nuclear test veteran group or control group, allowing the study team, including researchers at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, to make comparisons.

“In both nuclear test and control veterans’ samples, we found chromosome aberrations, including the more complex ones,” said Dr Anderson. “But overall, we found no statistical difference in the amount of chromosome aberration type between the two groups.”

Further investigation showed a higher-than-average occurrence of complex aberrations in a very small subset of the nuclear test veterans: including those who had been identified as having a higher likelihood for radiation exposure, based on the particular military operation they were on at the time of the tests. Analysis of the type of aberrations suggested that some of the damage was relatively recent, rather than from the time of the tests, reflecting ongoing exposures that are potentially from internalised radioactivity and/or medical procedures, the researchers deduced.

The researchers also combined the data from the M-FISH study with the data from their parents-and-child study from last year, which had looked into whether nuclear test veterans had passed on to their descendants more changes to their DNA in comparison to other veterans. Combining the data meant the researchers could look for any association between chromosome aberrations in nuclear test veteran fathers and the amount of newly arising genetic changes in their adult child – but there was no such association, they concluded.

In the previous study, the researchers had spotted that one particular pattern of changes to the DNA building blocks – known as SBS16, a mutation signature – happened more often in a small number of families of nuclear test veterans than in those of control veterans. As a result of this new part of the Genetic and Cytogenetic Family Trio study, the researchers spotted a weak relationship between complex aberrations and SBS16 in both nuclear test and control veterans. “This may represent a pattern consistent with radiation exposure in the father which is detectable in their adult child, although this remains to be established,” said Dr Anderson. “But when we focused on the families with higher SBS16 who had reported poor health in one of their descendants, that weak relationship wasn’t there, suggesting that those particular health issues are unlikely to be associated with historical radiation exposure.”

Summing up the study’s findings, Dr Anderson said: “We find no chromosomal evidence of historical radiation exposure in the cohort of British nuclear test veterans sampled for our study.” She noted that this was different to the findings and interpretation of a study, published in 2007, of New Zealand test veterans.

“Our findings should offer reassurance to veterans that attendance at nuclear test sites, by itself, was not associated with detectable levels of exposure to radiation,” she added.