Carnegie Mellon University Doctoral Researchers Shine in 3MT Championship

Nine doctoral students explained their complex research and its importance in under three minutes during the championship round of Carnegie Mellon University’s Three Minute Thesis (3MT) competition, held Thursday, March 14 in Tepper School of Business’s Simmons Auditorium A.

First place was awarded to Benjamin Glaser from Materials Science & Engineering(opens in new window). Second place was awarded to Sampada Acharya, who is studying mechanical engineering(opens in new window). Acharya also received both the People’s Choice Award — selected by the audience in the theater — and the Alumni Choice Award, chosen by online votes from alumni watching the livestream. Third place went to Nicole C. Auvil, who is studying chemistry(opens in new window) in the Mellon College of Science.

The event, which is in its ninth year at Carnegie Mellon, started at the University of Queensland in 2008 and has been adopted by over 900 universities across more than 85 countries worldwide. Helen and Henry Posner, Jr. Dean of the University Libraries Keith Webster(opens in new window), who brought the competition to CMU, served as host of Thursday’s finals.

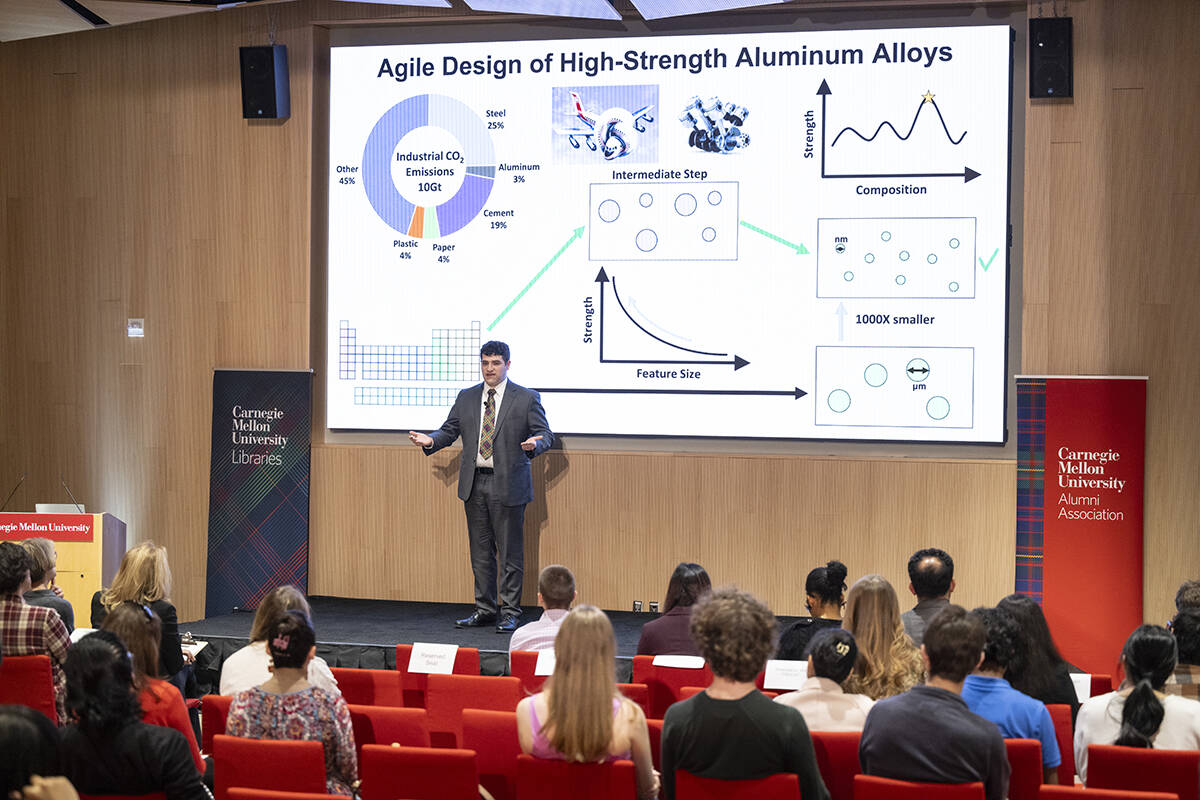

Glaser, a doctoral student in the College of Engineering(opens in new window), was excited to tackle the challenge that 3MT presents. He first tried to summarize his research informally for a group of friends after watching last year’s competition — and found that it was even more challenging than he expected.

“I thought it was a very interesting problem, to distill what takes us years just to understand, but then also conveying the importance and magnitude and methods to a general audience in such a short time,” he remembered. “This year when the registration came around I worked very hard to be able to make that connection successfully.”

In his research, Glaser is exploring an advanced material discovery model to create new aluminum alloys with high temperature strength and stability, and low cost and emissions.

“It’s a difficult problem that we need to be able to approach holistically, but I want people to understand that it is feasible,” he said. “In my presentation, I showed something actionable, not just simulations. I’ve already begun to get exciting results.”

Acharya, also from the College of Engineering, said she made such an impact on both in-person and livestream audiences due to the universality of her topic. Her research focuses on creating a device that can collect pathogens from surfaces, with the goal of making infectious places like hospitals less dangerous to visit.

“People don’t want to go to hospitals and then feel sicker — you go there in order to feel better and make others feel better as well,” she explained. “So my research, which addresses this huge gap that no one has really talked about in hundreds of years, spoke to everyone — especially in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, which really left its mark on people.”

To be truly successful, Acharya’s research requires collaboration from a variety of fields, and that’s why sharing her work with a campus-wide audience like the one assembled for 3MT was so important to her.

“This is an issue that everyone needs to work together to address — from computer scientists to mechanical engineers to roboticists to people working with artificial intelligence and beyond — and I hope that’s a takeaway from my presentation,” Acharya said. “This interdisciplinary audience is the thing that I really love about CMU. I can inspire them to think about how they can bring their work and their knowledge to try and address this gap.”

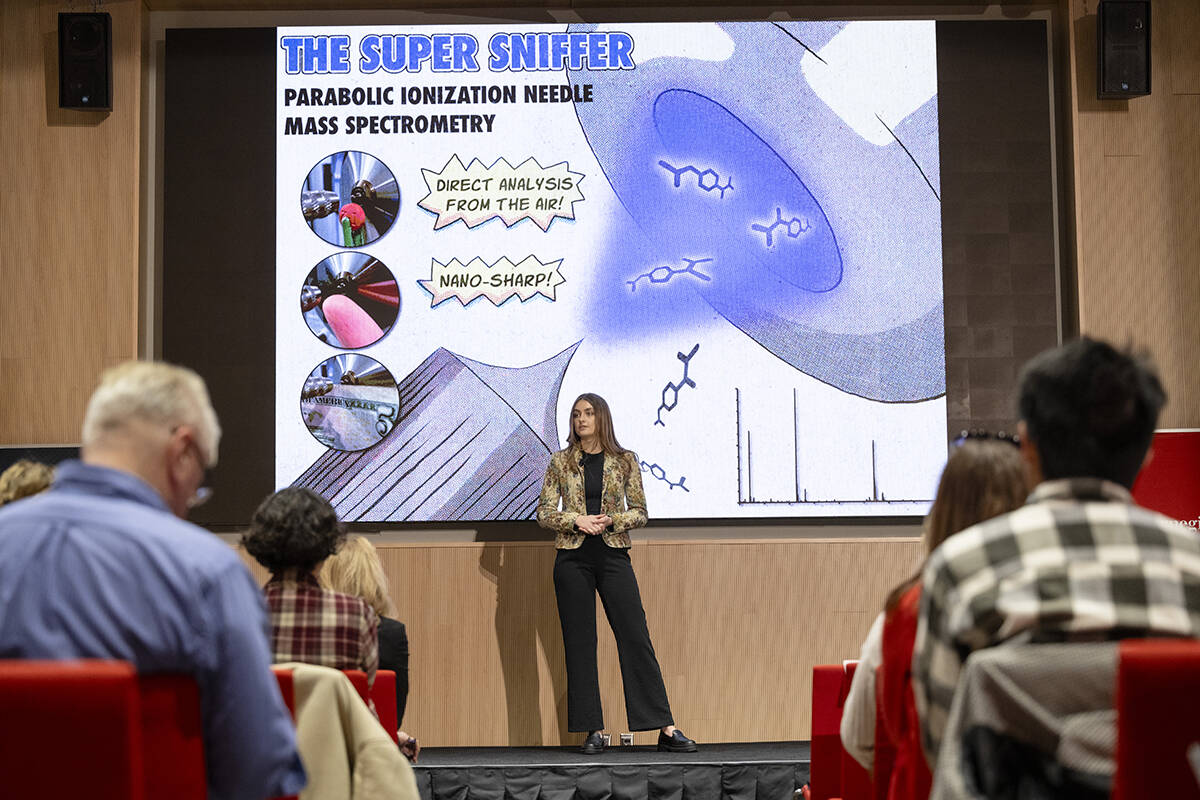

Auvil credits her successful presentation in part to her artistic slide design.

“I always try to put a lot of effort into the art side of science communication, which I feel is not given enough attention by a lot of scientists,” she explained. “Graphics and art can draw in people who wouldn’t normally be interested in science, and also help them understand it in a way that words just can’t. Visuals are a universal language; they can convey things that you’ll never be able to convey with words.”

She works with a chemical analysis instrument known as a mass spectrometer, which is essential for everything from testing environmental samples to crime scenes to historic artifacts — but it’s time intensive and expensive, and sometimes even damages samples. Her research has already yielded a new scientific device that attaches to a mass spectrometer to improve this process, which she named the “Super Sniffer” due to the way it detects chemicals emanating from samples, similar to the way a nose can detect chemicals in the air.

“I love the point I’m at now, where we can work on fun applications,” Auvil said. “Every time I talk to people about my work they suggest new ideas — even here at 3MT, today — and that’s why I love opportunities like this. Everyone has their own background that can inform what sort of applications would be important in their life, and not all of those are things that me or my advisor would think about on our own.”