RWTH Aachen: Unraveling the Enigma of an Abandoned Spanish Village

Here they are Sandgewand, Rurrand, or Feldbiss: Faults below the Earth’s surface. For geologists, they serve as a diary of sorts, documenting the Earth’s history. And there are such diary entries all over the world. Professor Klaus Reicherter heads the Neotectonics and Natural Hazards Teaching and Research Area at RWTH. Together with an international team of archaeologists, he has now solved the mystery of an abandoned medieval village in Spain.

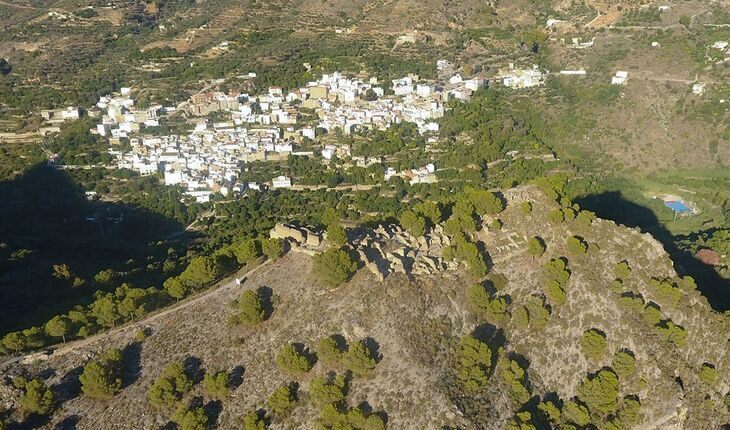

The ruins of Castillejo are clearly visible on Google Earth. Earlier investigations had already proven that the site had been inhabited since the beginning of the 11th century. But why was the rural settlement on a mountain near Granada abandoned in the High Middle Ages? The archaeologists were initially unable to find an answer to this question. Until they came up with the idea of bringing geologist and internationally renowned earthquake expert Klaus Reicherter on board. During his investigations, Reicherter was able to prove a “lost earthquake”, i.e. a quake that is not recorded in any chronicles. The experts have now published the solution to this archaeological-geological mystery in the journal PLOS ONE.

Normally, old records go back as far as the year 800 and also provide information about natural disasters. But: “After the Moors’ occupation of the area, which lasted until 1492, the Christians burned many of the old books and chronicles,” reports Reicherter. This led to much knowledge being lost. At the heart of the evidence of such events, which date back almost a millennium, are faults, i.e. cracks or fractures between two layers of rock. Early earthquakes can be dated depending on which rock layers are affected by the faults. This specialist area of tectonics is known as paleoseismology. Earthquakes that have not been recorded by modern equipment can thus be recognized and dated based on faults.

This also applies to the Sandgewand Fault that Reicherter and his team uncovered in a field near Schevenhütte on the northern edge of the Eifel. The Sandgewand Fault extends around 50 kilometers from the Wehebach Dam in a north-westerly direction via Stolberg and Eschweiler to the Netherlands. It is just one of several faults that run through the entire Lower Rhine Bay. “This fault undoubtedly occurred after the Ice Age,” explains the geologist.

Geologists use geophysics, i.e. radar technology and resistance measurements in the ground, to track down the faults. The surface can also provide clues, in this case water-loving plants whose growth stops abruptly at a line: “The fault is damming up the water here,” explains the expert. There is also water in the 20-meter-long excavation, the walls at the back are not supported and some of the earth has slipped away.

The expert stands ankle-deep at the edge of the excavation on this cold and wet April morning and is “really happy”. For him, the exposed layers of soil are “like a painting” and provide a wealth of insights. Wedges in the different layers, different colors, and fine white lines (indicating a glacial origin) tell the expert a chapter of the Earth’s history. It was initially assumed that the Sandgewand Fault was also the cause of the severe Düren Earthquake on February 18, 1756. Experts can, however, now rule this out with a fair degree of certainty, meaning that the Rurrand Fault was more likely the cause here. This is the work now underway in the Sierra Nevada in Spain: To find out which fault was responsible for the fatal earthquake around the year 1240.