UNSW Sydney’s Grace Karskens reveals the complex and controversial history of the Hawkesbury River in her latest book People of the River.

Professor Grace Karskens’ latest book People of the River: Lost Worlds of Early Australia is part of a new generation of more inclusive Australian histories.

“The new wave of Australian history combines Aboriginal and settler history,” the highly-acclaimed author and historian from UNSW Sydney’s Arts & Social Sciences says.

“It’s far more accurate because these two aspects were entwined in the past — so you can’t really write Australian history without Aboriginal history.”

The book takes readers back to the mid-1790s when ex-convicts built their bark huts on the banks of the Hawkesbury River, or Dyarubbin as it was known to local Aboriginal people.

Professor Grace Karskens. Photo: Joy Lai

The Hawkesbury/Dyarubbin River opens inland at Broken Bay, located along the east coast about 90 kilometres north of Sydney. Its sinewy vein wraps around to the west of Sydney where it connects to the Nepean River at Yarramundi Reserve.

“Aboriginal people were, and remain, very close to their Country,” Prof. Karskens says.

“Meanwhile, the ex-convict settlers were mostly rural people, who brought with them old traditions and beliefs about land.”

From the mountains to the lakes and lagoons, Prof. Karskens researched the ecology, geology, soil science and flood zones of the region to understand the two societies, their cultures and the outbreak of frontier war between them.

The painful history

Shortly after Captain Arthur Phillip established a convict settlement at Sydney Cove on January 26, 1788, he and his officers went searching and discovered the 120-kilometre stretch of fertile soil fed by the river.

But the area was already inhabited by the Darug people who had lived there for thousands of years, Prof. Karskens says.

“When they go to the Hawkesbury, they start kicking Aboriginal people off their own country, and this is [one of the reasons] why the outbreak of a major frontier war erupts,” she says.

Prof. Karskens says the settlers took Aboriginal children and stole and assaulted their women, heightening Aboriginal people’s growing distress, rage and anger.

“Imagine strangers raiding your house, taking your baby or toddler, and refusing to return them,” she says. “That’s what it was like for Aboriginal people.”

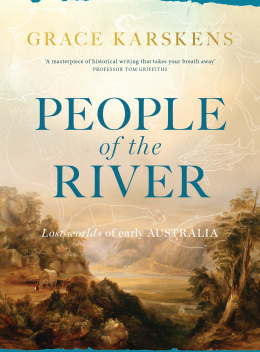

Professor Grace Karskens’ book People of the River: Lost worlds of early Australia (Photo: supplied)

Prof. Karskens says Australia’s human history is far older and deeper than the 232 years since British colonisation in 1788.

“On Dyarubbin, history goes back 50,000 years at least,” she says. “These original Aboriginal people lived through the last ice age and survived many cycles of climate change.”

The experience of convict settlers

To tell the full story of this tumultuous period in history, Prof. Karskens says, it is also necessary to look at the experience, culture and beliefs of the early ex-convict settlers.

“Just as the local Aboriginal people have their deep cultural history, so too did these early settlers,” she says. “So, we’re looking at two ancient cultures in the same space, and they both want the rich soils of the river.”

The settlers, who were mostly emancipated convicts, have traditionally been left out of history because they were “written off as hopeless failures”, Prof. Karskens says.

“But that is not true. These were the people who managed to stabilise the colony’s grain supplies as early as 1795.

“They recreated a familiar community on the river and their children led the first patriotic movement in modern Australia.”

Early settlers grew wheat crops fed by the rich soils of the Hawkesbury/Dyarubbin River. (Photo: Shutterstock).

Mining the truth about modern Australia’s origins

Prof. Karskens says the “common image” of the early colony as a “dumping ground” for Britain’s convicts is also incorrect.

“The colony was certainly intended for convicts, but it was deliberately and carefully planned,” Prof. Karskens says. “After their sentences ended, ex-convicts were given land and many became small farmers. They and their children were to create a new society in New South Wales.”

People of the River tells the stories of that period so “we can better understand what happened when this country was invaded”, she says. “I want people to understand and feel differently about Australian history. I want them to connect to it, to have a historical sense of place.”

The view of the Hawkesbury River from the lush hills of Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park. (Photo: Shutterstock)

Dyarubbin: the Real Secret River

For her next project Dyarubbin: The Real Secret River, Prof. Karskens is working with a team of Darug researchers, artists and educators to map over 170 Aboriginal names for places along Dyarubbin.

She stumbled on the long-lost list of names in Sydney’s Mitchell Library in 2017, which had been compiled in 1829 by Presbyterian minister Reverend John McGarvie.

“I was speechless. It was unbelievable – a shock – because I can’t tell you how rare it is to find something like that,” she says.

The project has been supported by the $75,000 Coral Thomas Fellowship from the State Library of New South Wales for 2018-2019.

Prof. Karskens and her Darug co-researchers are completing an online digital Story Map and a series of stories which will be published on the Dictionary of Sydney. Two exhibitions will follow in 2021.