ASU Study: Confusion Complicates US Recycling Efforts

In most major cities and buildings, recycling bins can often be found alongside trash bins in an effort to encourage recycling.

But is it working?

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the solid waste generated in the U.S. in 2018 was 292.4 million tons — or 4.9 pounds per person per day. Of that, only 32% was recycled.

Compare that with countries like Germany, which recycles nearly double that, and you see the seriousness of the situation.

Part of the problem is simple. Despite specific signage about what goes where, too often, trash is tossed in the wrong bins.

What a waste

Kevin Dooley, senior Global Futures scientist in Arizona State University’s Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory, decided to illustrate this problem. In 2019, he emptied everything out of the garbage and recycling bins onto the floor of a conference room as part of a waste audit experiment at The Sustainability Consortium Summit.

“There was a lot of garbage that should have been recycled,” Dooley said. “And a lot of items in recycling bins that didn’t belong there.”

There’s actually a name for the latter. It’s called wish recycling — when people stick trash that they hope is recyclable in the bins.

“There’s this attitude of … this should be recycled, so I am putting it in,’” he explained.

But it’s more than that.

Not all plastic is created equal

One of the assumptions that many people have is that all plastic is recyclable. So many confidently toss empty plastic bottles in the recycling bin like Seth Curry making a sure shot.

But not all plastic has a place in the recycling process. For example, plastic cutlery, straws, bottle caps, plastic chip bags and plastic-lined cups and lids can not be recycled.

Plastic bags are the most common item that is mistakenly put in the recycle bin, Dooley said.

“The norm is that plastic is not recyclable,” Dooley said. “It has to be designed and chemically reacted to be recycled.”

But that isn’t necessarily common knowledge.

According to a Greenpeace USA report that came out in 2022, of the 51 million tons of plastic waste generated by U.S. households in 2021, only 2.4 million tons, or 6%, were recycled.

There’s also often confusion around contamination — which can curtail recycling efforts.

Should an empty sauce or peanut butter jar be cleaned out completely? Just rinsed? Or is there someone in a recycling center somewhere with hot water and dishwashing liquid taking care of that?

City of Phoenix guidelines say recyclables should be clean, dry and empty before being placed in the recycle container: “Make sure the majority of food particles are either scraped or rinsed out. Just a quick rinse is all you need.”

Trust in the triangle

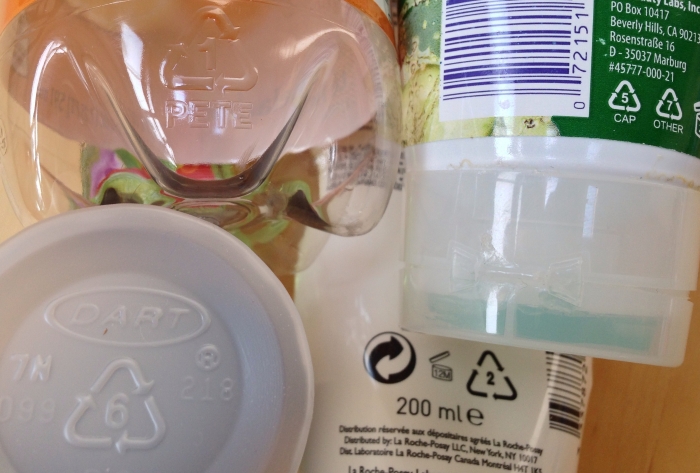

Adding to the confusion is the triangle label that’s placed on plastic products.

Like some sort of stamp of approval, many people assume that the logo made up of three circling arrows indicates that an item can be recycled.

But does it?

“The short answer is ‘no’ — it does not mean it is absolutely recyclable or will be recycled,” explained George Basile, professor of practice in the School of Sustainability.

Instead, it is an indication of the plastic’s potential for recycling and how it can be disposed of after use.

“While the triangle is made up of three arrows that represent recycling, there are a number of factors that make something really recyclable or not,” said Basile, an internationally recognized practitioner in the field of sustainability.

Inside the logo are numbers — 1 to 7 — a sort of code of communication to consumers. They signify the type of plastic used and if it is made of chemicals that may be unsafe for personal use.

The numbers have a range of meanings — from whether an item can be accepted by curbside recycling to its potential to cause serious health issues.

The people problem

Rajesh Buch, business development director for ASU’s Biodesign Center for Sustainable Macromolecular Materials and Manufacturing, points to the role consumers play in plastic pollution.

“The biggest problem with recycling is people’s behavior,” said Buch, “but there are many factors that affect that behavior.”

For starters, “We don’t have a consistent recycling standard of what can be recycled and what can’t be recycled,” he said.

For example, Buch adheres to one set of standards in Chandler, where he lives, and another in Tempe, where he works.

“There are 28 municipalities in the Valley, and they pretty much have 28 different recycling standards,” he said.

This mixes people up even more.

“Which then leads to apathy on the part of consumers,” Buch said.

Many organizations are pushing the federal government to come up with a national recycling standard, according to Buch.

“We might have one in the next few years, maybe in the next decade,” he said.

All this helps explain why the plastic problem continues to grow.

In addition to the plastic seeping into our seafood, a new study released by researchers at Ocean Conservancy and the University of Toronto in January found microplastic in 88% of the tested protein samples — including seafood, beef, pork, tofu and other plant-based meat alternatives.

A second study that came out of the conservancy at the same time found that a plastic liter bottle of water had 240,000 tiny particles, some so small that they can pass through the intestines and lungs directly into the bloodstream and other organs.

Sorting and other solid solutions

Solutions are complex. Obviously, there is no one answer to the problem but rather a combination of actions that can impact change.

Dooley points to Japan and European countries that take sorting very seriously — with separate containers for paper, aluminum, glass and more.

A container that is only for glass is less likely to be filled with food and other materials.

Germany, considered the best recyclers in the world, uses six separate containers.

New technology can both recycle plastic in its current state or recreate plastic that can be made of recyclable materials. The next step is to make it economically feasible to produce.

Dooley’s work at The Sustainability Consortium currently focuses on eliminating the problem of small-format plastic products and packaging recycling — things like pill bottles, dental floss and toothpaste tubes — which are not recyclable in most U.S. curbside recycling programs.

Basile and his team are researching products that will lead to a sustainable circular economy as opposed to a linear one — produce, consume, throw away.

“It can be more economically efficient — better for people and the entire planet,” Basile said. “After all, nature does it. So can we.”

Keep recycling solutions simple

While technical advances are essential, they still don’t address all the confusion over what goes in the recycling bins and what doesn’t.

To counter that confusion, Alana Levine says people need to take time to understand what can and can’t be recycled in their local recycling program and only purchase products that can be recycled.

Levine, director of Grounds Services and Zero Waste at ASU, recommends reading the city of Phoenix guide to recycling myths, which includes the myth that paper towels and tissue paper can be recycled — they can’t. Nor can food.

The university is working to reduce how much plastic is being used and sold, explained Levine.

For instance, the bookstores at all campuses have gone bagless, potentially eliminating 100,000 bags from being produced.

Last year, ASU athletics sold 5,922 reusable cups, with 38,741 refills, eliminating as many cups, lids and straws from being produced as waste.

When it comes to getting more people to recycle, Michelle Shiota says simplicity is the key to success.

“People don’t fail to recycle or make mistakes in recycling because they are stupid or unmotivated or don’t care,” said Shiota, a professor of social psychology at ASU. “They make mistakes because the rules are completely confusing and inconsistent from one place to another.

“If we want to change behavior we have to figure out how to make this easy — really easy.”

Shiota said that expecting people to know what can and can’t be recycled, where this goes and where that goes, how rules differ from town to town, what the recycle triangle really means and, finally, if a jar needs to be completely cleaned before it can be recycled is “not happening — not happening in any universe ever with human beings.”

“Even I don’t know all of that, and I’ve actually put a fair amount of time into trying to figure this out,” she said.

People don’t fail to recycle or make mistakes in recycling because they are stupid or unmotivated or don’t care. They make mistakes because the rules are completely confusing and inconsistent from one place to another.

Michelle ShiotaProfessor of social psychology at ASU

Shiota believes that people recycle less than we’d like them to or make mistakes in the process because the infrastructure that we provide for scaffolding that behavior relies on a huge amount of mental bandwidth that people simply do not have.

“When you’re finishing up your lunch and you’re already five minutes late for a meeting, nobody’s going to stand there and spend the next several minutes figuring out which of the 20 things they’re carrying can be recycled and which can’t,” she said.

Shiota said following Europe’s lead and having a wider range of recycle bins is a very good idea.

“If we provided six different bins that were clearly labeled about what goes into what, maybe Americans would do that too,” she said. “But we don’t.”

What’s needed to increase this behavior is clear, simple, explicit rules, that people learn early, that are frequently reinforced over and over and over, she said.

“The problem is people keep wanting to frame this as we need to get people to change,” she continued. “No — we need to change the infrastructure and the messaging. And then people will need to change less.”

“Simplify the system,” she said. “End of story.”