Carnegie Mellon University Successfully Launches Payloads Iris and MoonArk as Part of Historic Lunar Mission

A bright dome of light pierced the night. As the light grew brighter and larger, it rose into the sky, taking the shape of a rocket dashing into space, a trail of exhaust left to mark its path.

“Liftoff,” shouted Zach Muraskin, a senior studying physics(opens in new window) at Carnegie Mellon University and the science team lead for Iris(opens in new window), a rover bound for the moon hitching a ride on that rocket. “Go Iris!”

Muraskin and about 30 other Iris team members past and present huddled on a pier under an overpass to watch their rover hurtle into space. Wrapped in blankets and winter coats in weather more appropriate for Pittsburgh than Florida’s Space Coast, the team cheered, hugged, offered congratulations and more than a few shed tears.

“We made it,” said Divya Rao, a master’s student in applied data science(opens in new window) and the mission operations lead for Iris.

Follow Astrobotic(opens in new window) for the latest updates on Peregrine Mission One.

Payloads from CMU launched to the moon at 2:18 a.m. on Monday, Jan. 8, as part of America’s return to the lunar surface for the first time in 50 years. Iris, a tiny rover aiming for a big impact, and MoonArk, a collaborative sculpture project that is as much a work of art as an engineering marvel, rode aboard the rocket as it cleared the launch tower and arched toward space. The projects bring together students from every school at CMU and faculty and alumni to plant the university’s plaid presence on the moon.

“The launch of Iris and MoonArk is an extraordinary next step in America’s dream of returning to the moon,” said CMU President Farnam Jahanian(opens in new window). “It’s also an extraordinary dream realized for the students and faculty across Carnegie Mellon University who have inspired and orchestrated every facet of this mission. I am deeply grateful for Astrobotic Technology’(opens in new window)s partnership on this project and excited to see the doors to space exploration swing open wide for a new generation of scholars and innovators. Our entire community celebrates this important moment and offers our well-wishes for a smooth lunar landing.”

Iris and MoonArk are bolted to Peregrine, a lunar lander built by CMU-spinout Astrobotic on the foundation of decades of university research into space exploration. Peregrine — targeted to land on the lunar surface on Feb. 23 — is secured in the nose cone of United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan rocket. CMU is the only university with payloads on the historic mission.

The Iris mission is one of superlatives. The rover will be the first university-developed, student-led rover on the moon. It will be the first American robotic rover on the moon. It will be among the smallest and lightest on the moon. It will be the first rover to feature a carbon fiber chassis and wheels. Its featherweight, bottlecap-shaped wheels could open the door for new designs with new materials. The 2.2-kilogram, shoebox-sized rover could chart the future of planetary exploration.

Students put hundreds of thousands of hours into Iris over its development. Engineering students developed the computer, electronics and the iconic bottlecap wheels. A drama student led the design and initial development of the software the team will use in Carnegie Mellon Mission Control to communicate and drive the rover. Students from every school at CMU, including engineering, computer science, physics, data sciences, business, drama, design, music and English, were part of the design and development of the rover and will be part of the mission crew that will direct the rover’s movements on the lunar surface.

“This tiny rover sends a big message: space exploration is for everyone. Today’s launch sent the first university rover, developed and operated by students, on its way to the moon,” said Raewyn Duvall(opens in new window), research staff in the Robotics Institute(opens in new window) and a rover executive director for the Iris mission. “Iris demonstrates that the moons, planets, stars and beyond are within reach of those who persevere.”

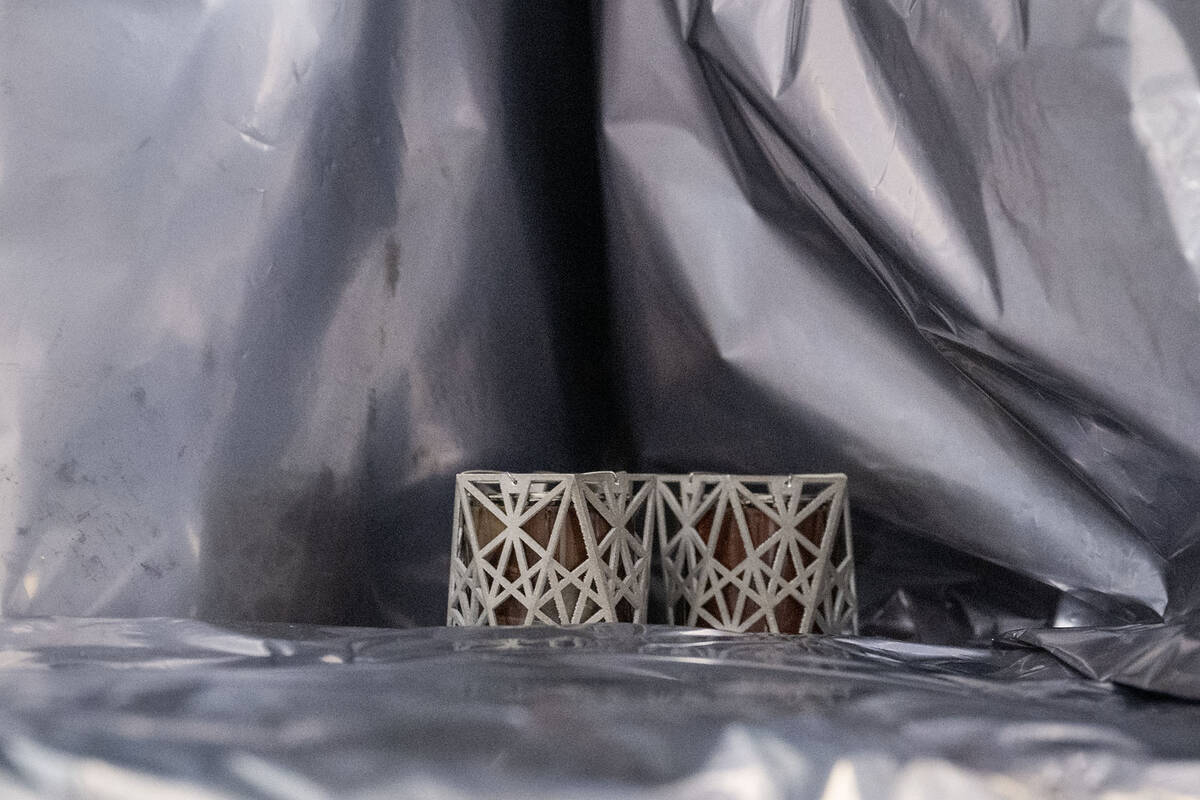

MoonArk will be the first museum on the moon. The 10-ounce cylinder comprises four small chambers made of titanium, platinum and sapphire that contain hundreds of images, poems, music, nano-objects, mechanisms and samples from Earth. Collectively, these items tell complex narratives integrating the arts, humanities, sciences and technology. MoonArk represents the work of 18 universities and organizations; 60 team members; and more than 250 contributing artists, designers, educators, scientists, engineers, choreographers, poets, writers and musicians.

The connection to the moon transcends known time. From scientists to artists to children, humans have long pondered the moon, wondered how it stirs the tides, affects the growth patterns of life and what lies beyond its gateway to outer space. MoonArk is meant to direct Earth’s attention outward into the cosmos and beyond and at the same time reflect to Earth as an endless dialogue about humanity’s context within the universe.

“The MoonArk is a technical miracle that celebrates the creative capacity of humanity; projecting forward a very hopeful message to future humans about collaboration, cooperation and a shared human experience,” said Mark Baskinger(opens in new window), director of the Joseph Ballay Center for Design Fusion at CMU and director of MoonArk. “It also questions how we are moving culture into extraterrestrial contexts that will be interpreted in the very distant future through very different cultural lenses.”

CMU is no stranger to space. Edgar Mitchell (ENG 1952) walked on the moon. Judith Resnik (ENG 1970) and Professor Jay Apt(opens in new window) flew on multiple space shuttle missions. CMU trustees Glen de Vries(opens in new window) (MCS 1994) and Lane Bess(opens in new window) (DC 83) traveled to space aboard Blue Origin’s New Shepard spacecraft. Bess took along his 23-year-old child, Cameron, making the two the first parent-child pair to travel into space together.

NASA has also looked to CMU for expertise for decades.

CMU robots have traversed the Chilean desert(opens in new window), stood at the lip of an Alaska volcano(opens in new window) and chased the sun across the Canadian arctic tundra(opens in new window) as part of NASA research projects. Vandi Verma(opens in new window) (SCS 2005) drives rovers on Mars.

Robotics Professor Zac Manchester sent a satellite swarm into orbit(opens in new window). Engineering Professor Brandon Lucia launched the world’s first batteryless nanosatellite(opens in new window). Physics Professor Matthew Walker is using data from the James Webb Space Telescope to uncover the nature of dark matter(opens in new window).

And that’s just a taste. Alumni work in the agency’s labs and research centers, and lead the startups paving the way for the next generation of discovery.

“It has been half a century since CMU boots walked the moon, and it is great to be heading back with our first robot,” said William “Red” Whittaker(opens in new window), faculty emeritus in the Robotics Institute who co-founded Astrobotic, mentored the Iris team and has been working on space exploration since the 1980s. “In space what counts is what flies. Our missions, tech and people live by that value. By every measure, Carnegie Mellon University is a space-faring university.”

Whittaker joined the team to watch the launch.

“Having put about two decades into this, that was really big for me,” he said after the rocket’s glow had disappeared from the sky. “I started dropping a tear when it went up.”

He paused, looked at the team and smiled.

“Now we have a job to do.”

As Peregrine approaches the moon, the Iris team will be busy with mission training and simulations. The real test comes after launch, after landing and once the rover’s wheels roll across the lunar surface for the first time. But the spirit of Iris was felt early Monday morning as the students counted down the minutes and the seconds, as they traced the rocket’s path of this planet and as they looked to the heavens for what’s next.

“Iris is more than just a shoebox on the moon with bottlecaps,” Nikolai Stefanov, a senior studying physics and computer science(opens in new window) and the mission control lead for Iris, said, referencing the rover’s size and distinctive wheels. “Iris is the late nights. Iris is the human century of effort that went into it. Iris is the members that are with us here today, and Iris is the members who aren’t. Iris is all of us.”