Examining Word Learning in Children Without Meaning

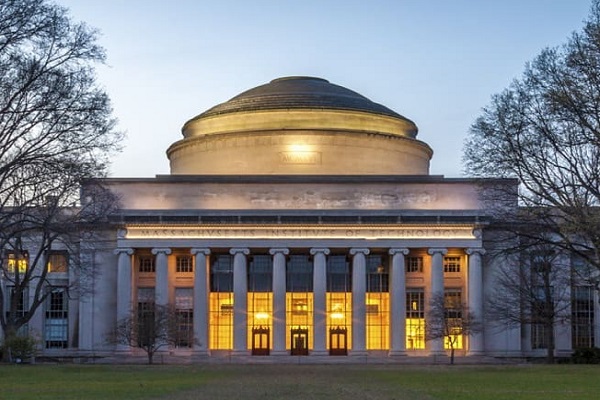

Researchers at the MIT Language Acquisition Lab are using funds from the 2022 Levitan Prize in the Humanities to carry out a set of studies investigating children’s acquisition of “expletives” or “dummy words” — words that don’t seem to have any meaning.

Associate professor of linguistics Athulya Aravind, who received her PhD in linguistics at MIT in 2018, was awarded the prize last year and has been leading this initiative.

Her research into first language acquisition involves looking at children’s developing understanding of what structures are allowed in their language, how those structures are interpreted, and how they may be used in conversation.

In English, expletives appear in sentences like “There is a book I would like to write” and “It is clear that the book will be fascinating.” In these examples, “there” and “it” contribute no meaning, but instead provide a filler subject so that the sentences satisfy the rules of English grammar.

“The standard assumption is that word learning is a process of mapping word-forms to meaning. Expletives are immediately interesting as they clearly don’t conform to this assumption,” Aravind says. “In this project we aim to ascertain how children learn expletives. We hope this might show something about the nature of these elements and also about the assumption that word learning involves mapping form to meaning.”

Languages tend to reuse existing words as expletives, so expletives usually have a meaningful counterpart, for instance “there” when it picks out a location (“Over there!”). One of the studies asks whether young children have access to both expletive and meaningful uses of words like “there” and “it.” Children heard ambiguous sentences like “It is fun to roll,” and had to decide which of two characters said it: one who was rolling around on the ground, or one who was rolling a snowball. If “it” is viewed as an expletive, the sentence could mean that the activity of rolling is fun; if “it” is a meaningful pronoun referring to the snowball, what is fun is rolling the snowball.

In this case, children not only were able to access both meanings of the sentence, but on average privileged the expletive treatment of “it.” Aravind suggests that this presents preliminary but indicative evidence that children expect some words not to have meaning, but only to play a formal role.

Using case studies

Along with associate professor of linguistics Martin Hackl, Aravind co-directs the MITLanguage Acquisition Lab, which studies how young children develop the ability to use and understand language. Child language has historically been an important source of evidence for linguistic theories, but in an era of large language models attention has shifted away somewhat.

“At the lab, we think that the fundamental question about human language is how children go from behaving as if they know very little about their language to basically talking like adults, while arguably having limited, impoverished, and messy data from which to learn,” Aravind says.

To inform these larger goals, the lab conducts case studies examining very specific domains of language, and assesses how language acquisition proceeds within the case study.

Working with Aravind on this particular study funded by the Levitan Prize is Megan Gotowski, postdoc in the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy. She completed her PhD at Rutgers University in 2022, and specializes in syntax, semantics, and first language acquisition.

“I was very interested in working with Professor Aravind on this project because I think our interests overlap very nicely,” she says. “Obviously if we’re asking these questions about how children learn words, we need to be able to account for how this process happens when there is a meaning component and what happens when this is really just a formal structural aspect of the language.”

Collecting the data

So, how does one get children to participate in linguistics studies? The lab has two main pools. One is a database of online participants, innovatively developed during the pandemic. All across the country parents will do a Zoom testing session with a researcher who plays online games with the kids, where the games are actually the studies.

But particularly with certain younger age groups, some studies are much better done in person. The lab partners with the Museum of Science, Boston on a live exhibit, collecting data with children visiting the museum.

“That helps better in getting a more controlled environment,” Aravind says. “But both online and in person, we put a lot of effort into making sure that the studies are not only scientifically sound, but also fun and engaging to the child.”

Any discussion of language acquisition today usually touches upon artificial intelligence. Aravind’s take is while the lab’s work can certainly contribute, further study is required to draw conclusions.

“Large language models strike me as incredible engineering accomplishments even if they raise a variety of ethical issues, especially when it comes to transparency and bias,” Aravind says. “They’re extremely sophisticated, and they might have great utility in a variety of domains. Nevertheless, I think at this moment, we don’t have a sufficient understanding of those systems to make a ‘cross-species’ comparison that informs how humans learn language.”

Funds from the prize have made it possible for the lab to collect initial data for a multistudy endeavor over a few years. The project could now be developed into a major grant proposal.

The Levitan Prize is an annual award given by the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences at MIT to recognize excellence in research and scholarship. The prize honors James A. Levitan, a professor of literature at MIT who taught for over 40 years and served as the dean of humanities from 1983 to 1988.