Experts Spot Closest Microbial Relatives Of Complex Life

In a new study, published in Nature this week, an international research group led from Wageningen University in The Netherlands presents the discovery of a group of microorganisms that represent the closest microbial relatives of complex life. The study reports that cells of this microbial group share several traits with cells from complex life forms, including plants, fungi, but also animals and humans.

Life on our planet can be divided into three major groups. Two of these groups are represented by tiny microbes, the Bacteria and the Archaea. The third group of organisms comprises all visible life, such as animals, fungi and plants – collectively known as ‘eukaryotes’. Whereas the cells of Bacteria and Archaea are generally small and simple, eukaryotes are made up of cells that are generally large and complex in their structure and organization.

The origin of eukaryotic cells, and in particular their complex features, has been subject of hot debate among evolutionary biologists. An international collective of researchers led from Wageningen University in The Netherlands has identified a microbial group belonging to the Archaea that represents the closest relatives of eukaryotic cells, providing new insights into the evolutionary transition from simple to complex cells.

New branch in the tree of life

In the late 70s of the previous century, the acclaimed biologist Carl Woese discovered the Archaea, a group of microorganisms evolutionarily distinct from bacteria that represented a completely new branch in the tree of life. He found that archaea and eukaryotes shared a common ancestry, but the exact relation between the two remained unclear for decades. This changed with the discovery of the Asgard archaea in 2015 – a diverse group of archaea that represent the closest microbial relatives of eukaryotes in the tree of life. Genomes of Asgard archaea were found to encode genes that they uniquely shared with eukaryotes.

Closest relatives of eukaryotes

In this weeks’ edition of Nature, researchers from Wageningen University, along with collaborators from Sweden, USA, Japan, China, Denmark and New Zealand, report several new Asgard archaea, and identify a specific subgroup, called Hodarchaeales, as the closest relatives of eukaryotes. Stemming from this discovery, the authors reveal important details on how eukaryotic cells obtained their complexity.

“The origin of the eukaryotic cell is one of the most enigmatic events in the evolution of life on Earth, and includes many important details that remain poorly understood. In particular, how eukaryotic cells obtained their complex and compartmentalized nature is subject to debate. In this study we identified a specific Asgard archaeal group – the Hodarchaeales – as the closest relatives of eukaryotes, and provide evidence that the genetic basis of some of the eukaryotic complexity can be traced back to the Asgard archaea”, says Thijs Ettema from the Laboratory of Microbiology, Wageningen University, who lead the scientific team that carried out the study.

“Our study involved many detailed phylogenetic analyses of genomic data to determine which microbial group represented the closest relatives of eukaryotes in the tree of life. Resolving such evolutionary relationships is extremely complicated since their last common ancestor dates back to some 2 billion years ago. Since then, the evolutionary signal needed to resolve their relationship has eroded due to the accumulation of mutations in their genomes.

Still, in a phylogenetic tour de force that spanned several years, we managed to identify Hodarchaeales as the closest relatives of eukaryotes”, says Laura Eme, former member of Thijs Ettema’s lab and co-lead author of the paper, currently heading her own research group at the Université Paris-Saclay in France.

The study also provided insight into the nature of the last common ancestor of Asgard archaea and eukaryotes.

High gene duplication rates

“We found that the Asgard archaeal ancestor of eukaryotes already possessed multiple genes for complex cellular processes that had only been found previously in eukaryotes. On top of that, we found that several of its genes evolved via gene duplication events. This is surprising, since archaea and bacteria, unlike eukaryotes, are known to mostly acquire genes from other microbes in a process referred to as horizontal gene transfer. The observed high gene duplication rates in Asgard archaea suggest that their genomes already evolved in a somewhat similar way as eukaryotes did”, says Daniel Tamarit, former member of Ettema’s lab and co-lead author of the paper, currently heading his own research group at Utrecht University in The Netherlands.

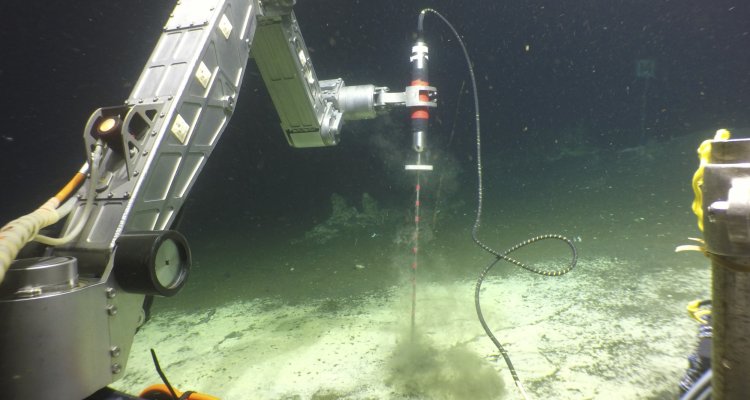

Studying Asgard archaea in more detail represents a prioritized goal for Thijs Ettema and his research group. Whereas his group has mainly been studying Asgard archaea by analyzing their genome data, he is currently also trying to grow them in his laboratory in Wageningen.

“Growing Asgard archaea in the lab is a long and tedious process, since they grow very slowly and their metabolism has not been well characterized. Yet, recently, some research groups have shown it can be done. I am sure that by studying Asgard archaea in more detail, we will reveal more important clues about how complex life evolved. The puzzle is getting more and more complete” concludes Thijs Ettema.