Fifty Years Into “Picturephones,” CMU Revamps Original Machine With Modern Twist

That’s how AT&T Bell Laboratories advertised its first commercial Picturephone in 1970. The print ad goes on to say that while it would be a lot of work to build a new type of communication network, “Picturephone service is a reality in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania,” and will soon be available in Washington, D.C., and Chicago.

“While FaceTime, Skype and Zoom are easily accessible these days, when video calling premiered, it was an expensive process reserved for the elite or major public events,” said Andrew Meade McGee, a CLIR postdoctoral fellow in the History of Science and Computing in the Carnegie Mellon University Libraries.

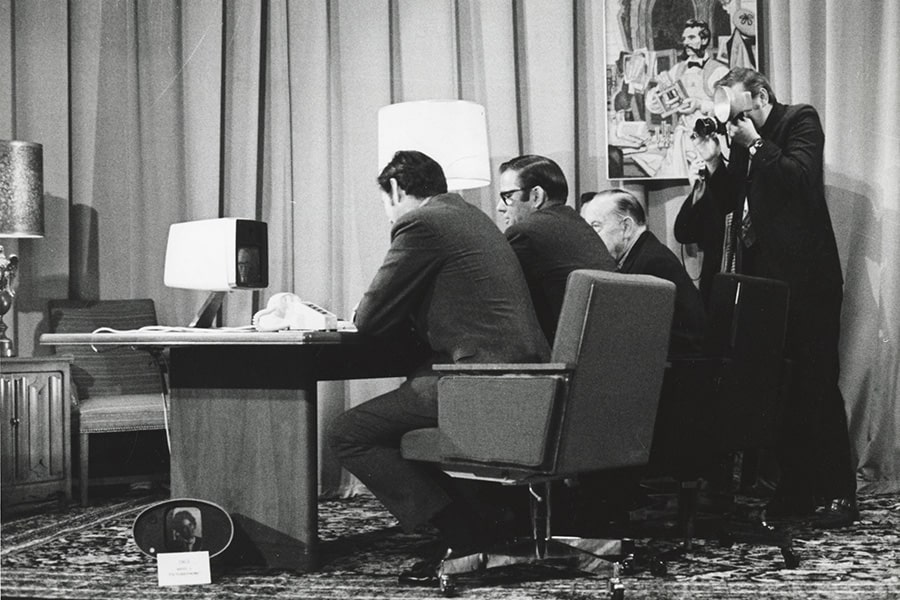

Mayor Peter Flaherty of Pittsburgh, Lawrence Barnhorst, vice president and general manager of Bell of PA, and George Bloom, chairman of PA Public Utility use the Picturephone on June 30, 1970 to call Alcoa Chairman John Harper.

“As soon as the telephone was invented, people thought about how to transmit more than just voices,” McGee said. Early 20th century forerunners of fax machines transmitted images over telegraph wires or radio waves, and the 1920s saw the earliest experiments with one-way videocall transmission. The post-World War II period brought efforts to design a reservable video booth system, which connected directly to other distant booths.

AT&T invested hundreds of millions of research and development dollars in videophone technology from the 1940s to the 1960s. The Mod I Picturephone appeared at the 1964 World’s Fair, but it was the Mod II model that ushered in the first commercial network for video calls.

“The Mod II was brought out of the laboratory and into the consumer experience as a viable system for everyday use,” McGee said. “Just two years before that, the film ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ showed people the futuristic technology of video calls, and then AT&T took concrete steps to bring it into the world.”

“It was cutting-edge technology at the time,” said Chris Harrison, an assistant professor in the School of Computer Science’s Human-Computer Interaction Institute and self-proclaimed amateur historian. “If you wanted to make a phone call in 1970, the analog audio signal would be transmitted on a phone line from one caller to another. But video is a different story.”

Video requires a much higher bandwidth than audio, and for this, the Mod II required three phone lines. One transmitted voice, just like a regular phone call. “They used some very clever techniques to compress the video onto just two additional analog phone lines,” Harrison said.

Harrison and McGee both had to see the Mod II for themselves, so in 2019 CMU Libraries purchased at auction a set of two of the Picturephones — originally owned by a Bell Labs engineer — still in their original packaging. “The wooden crate with 1970s foam was really disgusting,” McGee said. But the machines inside were impeccable.

Harrison said the sleek silver devices looked futuristic when they premiered, and that the exceptional quality is likely the reason they’ve survived so well. “We both thought it was a really beautiful piece of craftsmanship,” he said.

To get the machine up and running again, Harrison initially wanted to run video on the original hardware. “There’s no public manual that tells us things like how many volts the cathode ray tube (CRT) screen needs. Rather than risk the precious hardware, we set aside the original electronics and inserted a new telecommunications platform.” Harrison installed a computer with a modern screen and camera to simulate the original system.

While video calling technology has been changing incrementally for 140 years, McGee said it often takes disruption to see a sudden widespread adoption of technology.

“Wars and crises are what compel us to make changes to the technology we use. In World War II, there was a large acceleration of tech like rockets, radar and signal processing. Vast sums of money were thrown at seemingly intractable problems. We don’t like to move out of our spheres of normalcy, but when we have to, we’ll adopt things that previously seemed outlandish,” he said.

Harrison noted that today’s global pandemic, which has forced everything from board meetings to play dates online, has done just that for communications technology. “We now have a perfect storm of people with general exposure to the technology that’s been around for a long time, and a sudden society-wide need to solve a problem.”

As for what’s next, McGee said the new ubiquity of video conferencing will inevitably highlight glitches in the technology, but will also inspire visionaries and entrepreneurs imagining what the future could hold. “People will be out there pushing the boundaries of communication. Slightly behind that will be new social norms and a regulatory response by the state and markets to set parameters and policies for video conferencing.”

Harrison said, based on personal experience, he can imagine a lot of people suffering from so-called “Zoom fatigue.”

Both researchers agree that looking at where technology came from can offer a good idea of where it’s going.

“Academia is about standing on the shoulders of giants,” Harrison said. “You have to deeply understand that history if you’re going to push it forward. Fifty years ago the picturephone planted the seeds of what was possible even though it was a commercial failure. Most of what I do in my lab is largely impractical today, but 50 years from now may be mainstream. These things aren’t created in vacuums, so you need to have a human-centered vision of computing.”

CMU University Libraries supports that vision. It houses a cross-campus, interdisciplinary group called HOST@CMU, or the History of Science and Technology at Carnegie Mellon University. And among the Libraries’ Special Collections is the Traub-McCorduck Collection, which includes more than 50 calculating machines, letters, books and two Enigma machines. Now the collection also includes the pair of vintage AT&T Picturephones, which were purchased with the support of the Hunt family.

CMU Trustee Tod Hunt is the great-grandson of Alfred Hunt, who co-founded the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa) with six other entrepreneurs in the parlor of his Pittsburgh home. Tod’s grandfather and grandmother – Roy and Rachel – donated the money for the construction of CMU’s Hunt Library in 1960. And his family’s nonprofit, the Hunt Foundation, provided the funds to purchase the vintage AT&T Picturephones that now housed in Hunt Library’s Special Collections.

To celebrate the 50-year anniversary of the first commercial video call, Carnegie Mellon University hosted an event with Pittsburgh Mayor William Peduto and Alcoa Chairman Michael Morris on June 30, 2020. Their predecessors, Mayor Peter Flaherty and Alcoa’s John Harper, used AT&T’s “Picturephone” system on June 30, 1970.

That very model of Picturephone, the Mod II, was publicly demonstrated for the first time in Pittsburgh, where the commercial video calling service began. On June 30, 1970, then-Pittsburgh Mayor Pete Flaherty spoke “face-to-face” with the former chairman of Alcoa, John Harper. The two men were about a block away from each other.

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the event – June 30, 2020 — the School of Computer Science and University Libraries collaborated to recreate the call. Current Pittsburgh Mayor William Peduto and Alcoa Chairman Michael G. Morris spoke via video chat, as their predecessors did a half century ago. Following the call, a panel of CMU scholars including Harrison, McGee and Molly Wright Steenson, senior associate dean for research in the College of Fine Arts, hosted a live Q&A, discussing the history and legacy of the Picturephone’s launch.