Making a difference: UBC students design low-cost ventilator for COVID-19

This story is part of the “Making a difference” series, in which we shine a spotlight on the many ways—both big and small—that UBC community members are helping with the response to COVID-19. Share your story with us at [email protected].

UBC engineering students have developed a simple, low-cost COVID-19 ventilator that may very well save lives. Their design—built around a modified BiPAP machine—is among the final 10 in the Code Life Ventilator Challenge, an international competition that has attracted more than 1,000 teams from 94 participating countries.

The competition, hosted by the Montreal General Hospital Foundation and McGill University Health Centre, invited participants to design a ventilator that can be manufactured easily anywhere in the world and adheres to compliance specifications. Final results will be announced by the end of the week.

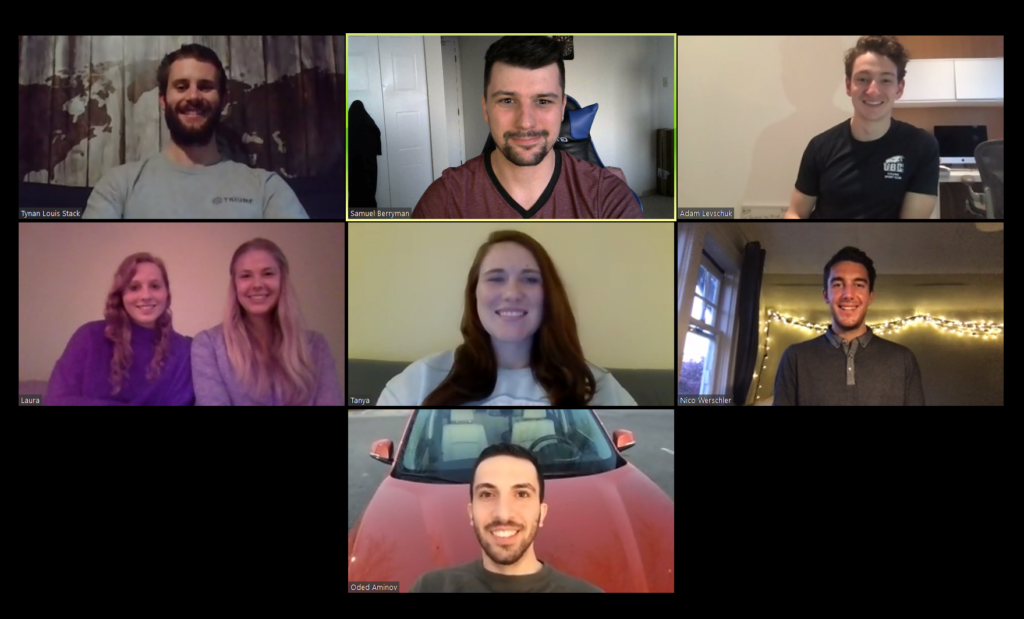

The team, which calls itself FlowO2, includes Oded Aminov (master in biomedical engineering), Tanya Bennet (PhD biomedical engineering), Sam Berryman (PhD mechanical engineering), Georgia Grzybowski (master in biomedical engineering), Adam Levschuk (master in biomedical engineering), Tynan Stack (mechanical engineering alumnus), Laura Stankiewicz (PhD biomedical engineering) and Nico Werschler (PhD biomedical engineering).

The students came up with the idea of customizing the BiPAP machine, which has been used for years to treat sleep apnea.

“Instead of building a ventilator from the ground up, we decided to use the BiPAP machine because it’s already approved for medical applications and people know how it works,” explains team member Laura Stankiewicz. “This allowed us to focus our efforts on writing the special software needed and securing additional parts—which are easily sourced from hardware stores or online suppliers—that would turn it into a potential life support tool for people with COVID-19.”

“Where conventional ventilators cost from $25,000 to $50,000, our invention should cost only a few thousand dollars to manufacture—and most of that is from the cost of the BiPAP machine,” says team member Nico Werschler.

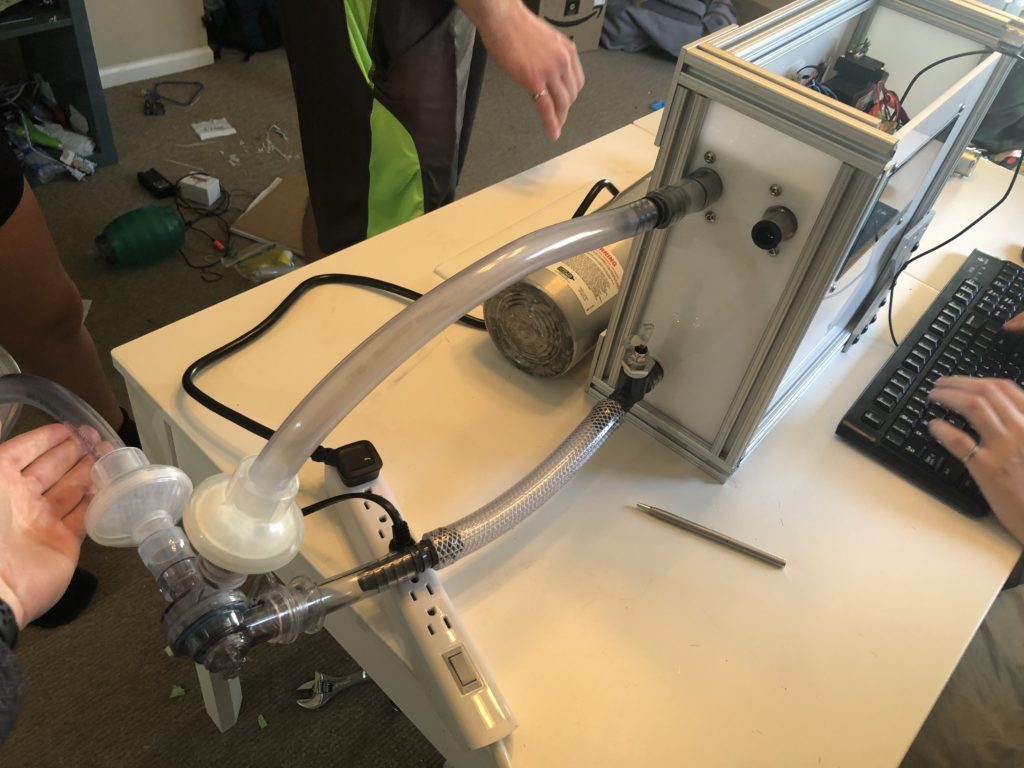

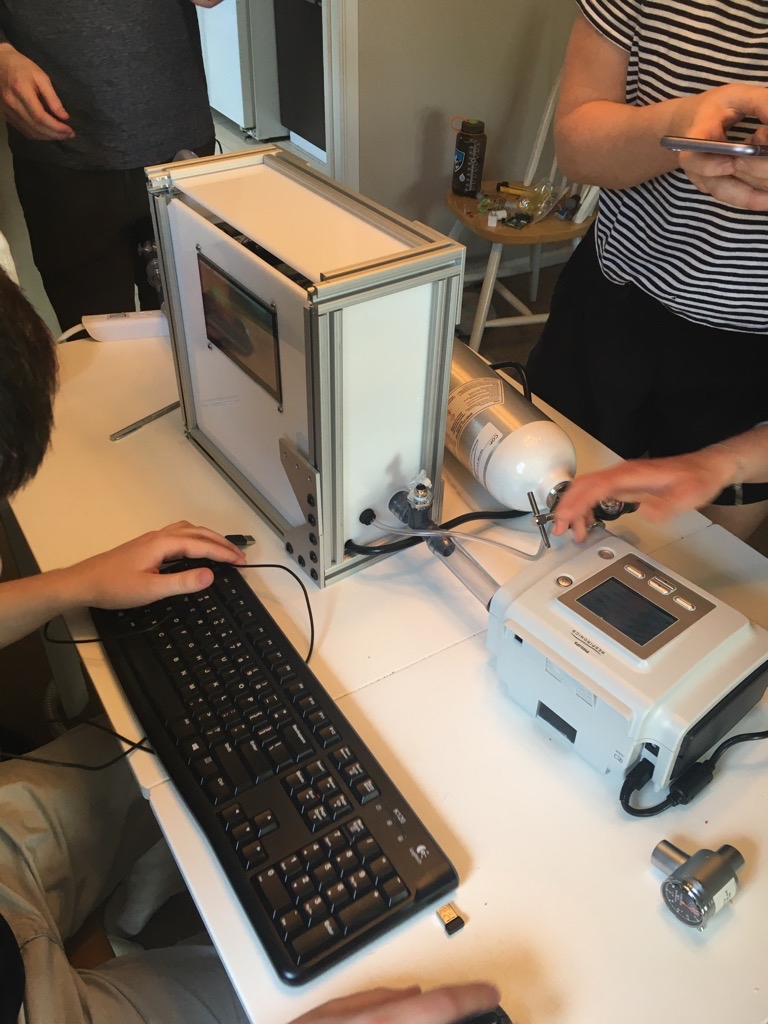

Customized BiPAP machine.

Modified BiPAP machine.

The FlowO2 team connecting on Zoom.

The team organized quickly after learning of the design challenge, communicating through Skype and reaching out to faculty mentors, parts suppliers and medical experts as they developed the ventilator. They received feedback from clinicians across Canada and from Mount Sinai in New York. Funding was provided by the Engineers in Scrubs program and the faculty of applied science, alongside donated equipment from the Provincial Respiratory Outreach Program and testing and fabrication support from TRIUMF.

In just two weeks, the team had a prototype ready to ship out to Montreal for evaluation.

“When the students saw this challenge, they just jumped on it like nothing else,” says Dr. Roger Tam, director of the Engineers in Scrubs program and an associate professor of radiology in the faculty of medicine. “It presented a great opportunity not only to put what they’ve learned into practice, but also to potentially make a major real-world impact.”

The ventilator was assessed on members of the team and a test lung at McGill University, producing what team member Adam Levschuk calls “very promising results.” It will soon be further evaluated at a simulation centre in Vancouver General Hospital and test lungs at TRIUMF.

“The next steps for us are to use our competition results to further improve our system,” says Levschuk, a master’s student in biomedical engineering. “We’ll continue to improve upon the components we use — whether that means sourcing cheaper, more accurate or more robust materials. Within the next couple weeks we will make a final push to get our BiPAP-to-ventilator augmentation kit approved by Health Canada. Our ultimate goal is to make a low-cost and readily available system that will make a meaningful impact to the health authorities who use it.”

“This is Canadian innovation at its best: aligning cutting-edge research capability with positive societal impact,” says Walter Merida, associate dean in the faculty of applied science. “The COVID-19 outbreak has had a significant impact on the economy, and the FlowO2 team exemplifies the type of leadership and talent that will be required to ensure Canada’s recovery.”

MEDIA: The students’ prototype ventilator is currently in Montreal, but still images, a demo video and stringouts are available here.