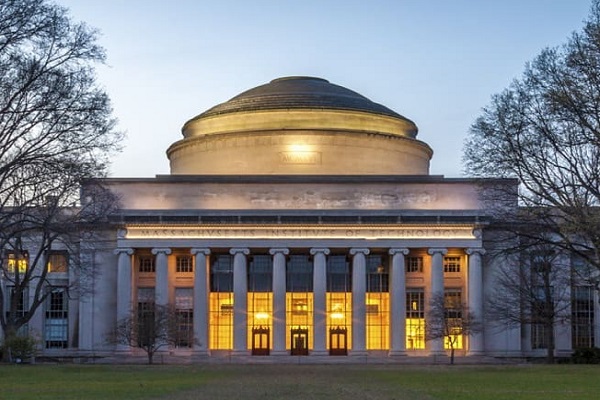

Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Building a decentralized bank for micro businesses in Latin America

In Barranquilla, Colombia, Edinson Flores has run a small, family-owned fast-food business for many years. But when his family became sick with Covid-19, he had to stop working and pay for medical care. When his family recovered, Flores still had customers and equipment, but he couldn’t afford the supplies he needed to get his business running again. He applied for a loan at a local bank but was denied because of his low credit score.

The situation was not unique: Small businesses like Flores’s make up the bulk of the economy in Latin America. Most operate in the informal economy and are not fully recognized by the government, making it difficult to get loans to grow or survive volatility.

That’s what Quipu Market is trying to solve. The company, founded by two MIT alumni, is using data from the informal economy to offer a series of small loans to entrepreneurs. Quipu has developed an online marketplace that helps entrepreneurs publish product catalogs, record transactions, and increase their sales. By digitizing business activity, Quipu is able to assess credit worthiness in a new way and provide loans at rates comparable to traditional banks.

“It’s all about using new data and networks to help entrepreneurs not only access financial products, but create wealth, because if you don’t create wealth, then the money is not ultimately improving the economy,” Quipu co-founder and CEO Mercedes Bidart SM ’19 says.

For now, Quipu is the one providing the loans, which gradually increase as entrepreneurs demonstrate the ability to pay them back. By the end of this year, the company plans to open up its blockchain-based lending system to allow anyone to buy interest-bearing tokens with money that is then allocated to entrepreneurs using Quipu’s algorithms assessing credit worthiness.

“We see ourselves as a digital, decentralized bank,” says Bidart, who co-founded the company with Juan Constain SM ’18 and Viviana Siless. “On top of the microloans, we want to add financial services and become a decentralized bank tailored for the informal economy.”

Quipu already has more than 10,000 users on its platform across Colombia, including Flores, who was able to access Quipu’s loans based on his strong customer base and not only get back up and running, but grow his business.

Finding a new path

Before coming to MIT, Bidart had worked for a think tank in her home country of Argentina to craft economic development policies. She also helped a grassroots organization that worked with families in informal settlements. But she began questioning if the grassroots work could scale, while also seeing that the top-down government approach was limited by a lack of data on the informal economy. She came to MIT to learn how to overcome those problems.

Bidart joined the Department of Urban Studies and Planning (DUSP) in 2017. While studying under associate professors J. Phillip Thompson and Gabriella Carolini, she was introduced to new financing models that centered around social banks, community currencies, and the blockchain. She also worked with Katrin Kaeufer, a research fellow at DUSP’s Community Innovators Lab.

“I started wondering how we could implement those models in places where there’s scarcity and economic urgency all the time,” Bidart says.

Although she came to MIT without a finance background and with no knowledge of startups, she started taking entrepreneurship classes at Sloan School of Management and eventually received support through the PKG Center and the MIT Innovation Initiative to explore her ideas further.

“When I got into MIT, I knew there was a problem and I had been thinking about solutions,” Bidart says. “But I had no idea there was this other way of doing things — not through grassroots work or public policy or big companies — but actually starting something myself that could scale using technology.”

Bidart spent the summer of 2018 designing a prototype financing system with a group of entrepreneurs living in a public housing complex in Baranquilla, Colombia. When she returned to MIT, she continued developing the platform and partnered with Siless and Constain.

In 2019, the co-founders got into the School of Architecture and Planning’s MITdesignX accelerator, an experience Bidart calls “game changing” because the program helped them realize they could build a profitable business around the new data they were collecting.

Today when entrepreneurs make a profile on Quipu’s platform, the company digitizes information like the location of the business, the goods or services offered, and who their customers are.

“We turn that social capital into economic capital with an artificial intelligence-based algorithm that assesses credit worthiness in an alternative way,” Bidart says. “We create a credit score that serves as a digital financial ID. With that ID, they can access rotative loans that start at around $25 and increase in value as users repay.”

Many of Quipu’s entrepreneurs have poor credit scores and cannot access traditional loans from banks. Private financiers are available, but they charge high interest rates and can use violent collection practices. Bidart says other microfinance solutions are slow to disperse money because they rely on people to travel to businesses and analyze operations, while Quipu can disperse money within three days of a request.

Quipu is building a blockchain-based system so that the tokens tied to its loans will increase in value as users repay the loans and pay back interest. The system will allow anyone in the world to loan money to entrepreneurs on Quipu’s platform.

Transforming economies

Quipu is currently operating across Colombia and planning to expand to Mexico by June of next year. Bidart sees Quipu as an engine of economic growth for lower-income neighborhoods that have been overlooked by traditional institutions.

“The problem is people don’t have access to financial products that are designed for their economy, so then there’s no economic development,” Bidart says. “Supporting people with loans and providing them with other ways to sell more can improve how their business works, and they can start using the data they already have to access not just our loans but other financial services at better rates.”

Better borrowing rates will even the playing field for families that have historically had to pay more for a number of financial services.

“We want to shift the reality that being poor is very expensive,” Bidart says. “Being born poor forces you to accept higher rates from banks, and it forces you to access supplies at higher rates because you are far away from the city or there’s a lot of middlemen. And what we want to do is say, ‘It doesn’t matter where you were born. We all have data around what we are doing —non-financial data that we can use to assess credit worthiness — and that will give all of us the ability to grow financially at the same rates.”