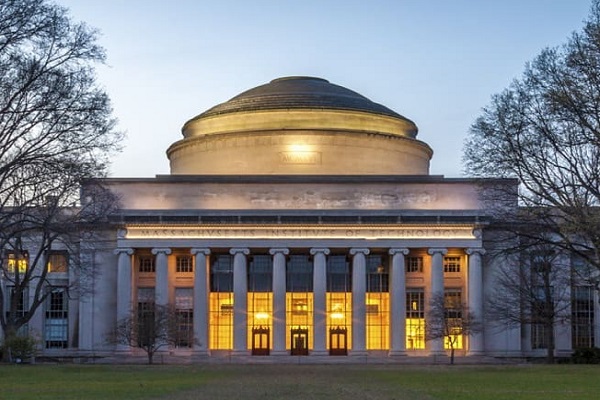

Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Reviving war-game scholarship at MIT

War games and crisis simulations are exercises where participants make decisions to simulate real-world behavior. In the field of international security, games are frequently used to study how actors make decisions during conflict, but they can also be used to model human behavior in countless other scenarios.

War games take place in a “structured-unstructured environment,” according to Benjamin Harris, PhD student in the Department of Political Science and a convener of the MIT Wargaming Working Group at the Center for International Studies (CIS).

This means that the games operate at two levels — an overarching structure conditions what kind of moves players can make, but interactions among team members are unstructured. As a result, people with different backgrounds are forced to engage and learn from each other throughout the simulation. “The game goes where the participants take it,” says Harris.

MIT researchers have been developing the craft of war gaming since the late 1950s. In “The Pioneering Role of CIS in American War Gaming,” Reid Pauly PhD ’19, assistant professor at Brown University and a CIS research affiliate, credits the origins of modern war-gaming methodology in large part to MIT professor Lincoln Bloomfield and other faculty affiliated with CIS.

Today, CIS is again at the center of new developments in the methodology, pedagogy, and application of war gaming. Over the last few years, CIS and the MIT Security Studies Program have responded to an increased demand for war gaming among students and from the policy community. This has resulted in new course offerings, student and faculty-produced research, and on-campus simulations.

Learning through games

PhD student Suzanne Freeman and Harris started the Wargaming Working Group as a forum for students to engage with the war-gaming community on campus and in policy spaces. Now in its third year, the group has developed a partnership with the Naval Postgraduate School (NPS) that brings mid-career military officers and academics together for an annual simulation.

Richard Samuels, Ford International Professor of Political Science and director of CIS, participated in his first crisis simulation in a game organized by Bloomfield, and subsequently organized nearly a dozen large-scale games at MIT in the 1990s through the early 2000s, most focused on Asia-Pacific security dynamics. Eric Heginbotham PhD ’04, a principal research scientist at CIS, and Christopher Twomey PhD ’05, were active participants. Together, they established the working group’s partnership with NPS, where Twomey is associate professor.

This year, participants worked through a crisis scenario centered on a nuclear reactor meltdown in Taiwan. Teams were assigned to represent Taiwan, China, the United States, and Japan, and the game was designed to tease out how civilian and military sub-teams would communicate during a crisis. Freeman and Harris presented some of the findings from the war game at Georgetown University in October 2021.

In addition to planning tabletop exercises at MIT, the working group invites speakers from universities and think tanks to present war-gaming research, and held online war games when MIT went virtual due to Covid-19. The working group has been especially successful at bridging the gap between academia and policy, allowing for PhD students and military officers to learn from each other, says Freeman.

For students hoping to further explore the history and practice of war gaming in a classroom setting, MIT now offers “Simulating Global Dynamics and War,” co-taught biennially by Samuels and Heginbotham. Students participate in four war games over the course of the semester — an operational war game, political-military crisis game, experimental game, and a game designed by students as their final project.

While the class is designed for security studies students and military fellows, it has included students and practitioners from other fields interested in incorporating gaming into their work. Lessons from the course can be applied to issues such as a global pandemic or refugee crisis, says Heginbotham.

For MIT undergraduates taking coursework in political science, war gaming is also a pedagogical tool used to consider the implications of policy decisions. In fall 2021, students in Erik Lin-Greenberg’s National Security Policy class participated in a simulation centered around a cyberattack on U.S. soil. Students worked in teams to represent U.S. government agencies at a National Security Council Principals Committee meeting. Lin-Greenberg is assistant professor of political science at MIT.

The revival of war gaming

Political scientists are increasingly considering how the method of war gaming can be improved and used in research and pedagogy. For scholars of interstate war and nuclear weapons, war gaming is an especially promising research tool.

Over the last decade, researchers have recognized that “war games and crisis simulations may have had an outsized influence on Cold War policymakers,” says Samuels. “Close, archival, analysis of Cold War games could provide insight into how policy elites thought about nuclear war.”

At the same time, the rise of the experimental method for political analysis has coincided with the revival of war gaming as a research tool, according to Samuels. “Experimental war games allow researchers to derive generalizations about leadership choice under stress,” says Samuels. However, scholars still face challenges related to external validity, or, the extent to which outcomes of war games apply to real-world scenarios.

In addition to advances in experimental war gaming and nuclear simulations, Heginbotham adds that scholars are increasingly applying war gaming to emerging and nontraditional security challenges. “War gaming allows scholars to model complex conflicts, change individual variables, and run multiple iterations,” says Heginbotham. For researchers trying to understand the dynamics of political events, gaming has a number of advantages.

In January 2022, Steven Simon, a former diplomat and National Security Council director now serving as a Robert E Wilhelm Fellow at CIS, wrote an opinion piece in The New York Times with Jonathan Stevenson about the need for war gaming focused on U.S. democratic backsliding. For Simon and Stevenson, war gaming is a tool scholars can adopt while studying low-probability but high-risk events like the Jan. 6 storming of the U.S. Capitol.

They argue, “War games, tabletop exercises, operations research, campaign analyses, conferences and seminars on the prospect of American political conflagration — including insurrection, secession, insurgency, and civil war — should be proceeding at a higher tempo and intensity.”

A bright future for war gaming

Lin-Greenberg ’09, MS ’09 joined the Department of Political Science and the Security Studies Program in 2020 after completing a dissertation that pioneered the use of experimental wargames in international security research. As part of his doctoral research at Columbia University, he ran a war game with military audiences to understand how drones impact escalation dynamics. He wrote in War on the Rocks, “The experimental wargames revealed that the deployment of drones can actually contribute to lower levels of escalation and greater crisis stability than the deployment of manned assets.”

At MIT, Lin-Greenberg, Samuels, and Heginbotham co-convene the Wargaming Working Group, mentor PhD students working on war-gaming research, and continue to advance the field of war-gaming methodology.

With co-authors Pauly and Jacquelyn Schneider, Lin-Greenberg published “Wargaming for International Relations Research” in the European Journal of International Relations in December 2021. The article establishes a research agenda for war gaming and highlights some of the methodological challenges of using war games.

The authors “explain how researchers can navigate issues of recruitment, bias, validity, and generalizability when using war games for research, and identify ways to evaluate the potential benefits and pitfalls of war games as a tool of inquiry.” One of these benefits, according to the authors, is the ability of war gaming to provide new data and help answer challenges and questions about human behavior and decision-making.

For Heginbotham, there is something unique about designing and participating in war games where decision-making under pressure leads to learning. “The data you uncover in the process of designing a game and the lessons you internalize while playing the game, would be very difficult to create in any other setting,” he says.

Likewise, Samuels is optimistic about the role of war gaming moving forward. He explains that the future of war gaming is bright so long as organizations — political, educational, industrial, military, and civic — continue to recognize the need to train future leaders in decision-making. Samuels is fond of quoting the Nobel laureate Thomas Schelling, a pioneer of civil-military war gaming while at Rand in the late 1950s and a partner of Lincoln Bloomfield at CIS, who once wrote: “Games won’t play music or cook fish, cure a man of stuttering, or improve my children’s French, just as they may not predict Pearl Harbor. But unless [critics] can show that games would have accentuated the tendency to ignore Pearl Harbor … [they] might have taught us something else useful.”