Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Uncovering the rich connections between South Asia and MIT

In 1884, an article in a widely circulated Indian nationalist newspaper expounded on the value of a technical education for Indians who were being denied such opportunities by the colonial British state. Even though MIT was barely more than two decades old, the author pointed to the Institute as a model of technical learning for the colony to aspire toward.

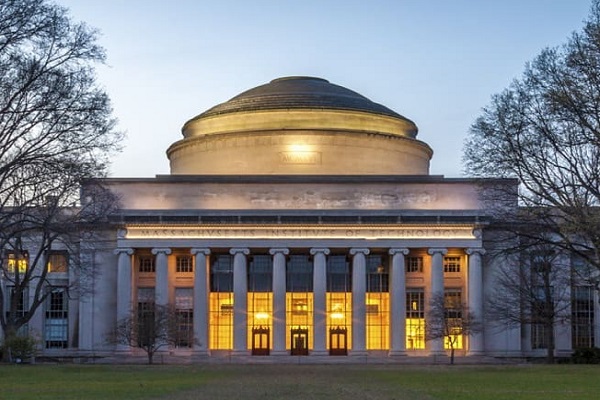

In ensuing decades, despite strict immigration laws in the U.S., an increasing number of South Asians came to MIT, which was one of the most international universities in the country. When India and Pakistan finally gained independence in 1947, a host of MIT graduates helped lead the development of the new countries. Universities modeled after MIT sprung up across India and Pakistan — some even including Infinite Corridors and Great Domes.

Such stories illuminate the longstanding, remarkably deep connections between South Asia and MIT. Those connections, and the people behind them, are the focus of a new exhibit on campus that explores the many ways that MIT has shaped South Asia (including India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Nepal) and that South Asians have shaped MIT.

The project, titled South Asia and the Institute: Transformative Connections, is the result of a research collaboration that involved a special subject class in MIT’s Department of History, with support from the board of MIT’s South Asian Alumni Association and the MIT International Science and Technology Initiatives (MISTI) MIT-India program. It will be on display in the Maihaugen Gallery throughout the year, with content also accessible online beginning in the spring.

“I think the biggest takeaway is the breadth and scope of connections between the subcontinent and MIT,” MIT-India Managing Director Nureen Das says. “The first South Asian student came in 1880 — it’s mind-blowing. Walking around this [exhibit], you see how all of the South Asian countries are integrated into all of the different schools at MIT and really infused into the community.”

A central focus of the project was to capture the personal stories of the pioneering South Asian alumni. Those stories, as the exhibit shows, are inextricably linked to the history of MIT, the U.S., and the South Asian subcontinent more broadly, and they offer a window into issues like immigration and race in the U.S. and decolonization and nation-building in South Asia.

“There’s an interesting way in which we can look at an institution such as MIT and broaden it to make a comment on the larger historical trends that we are all wrapped up in today,” says Associate Professor Sana Aiyar, who led student research efforts. “Even if you think about students from Ukraine or Russia at MIT today, you see that world events change how institutions think about their relationships to countries. But it’s the students and faculty — the human beings — who are ultimately affected. The repercussions of [state and institution policies] are all experienced individually.”

Histories bound together

As they conducted their research, the students from MIT and Wellesley College repeatedly discovered the histories of South Asians at MIT woven into the larger histories of MIT, the U.S., and South Asia.

The U.S.’ troubled history with immigration, for instance, was on display in the story of MIT’s first South Asian-American student, Madan Bagai. Bagai’s father lost his U.S. citizenship to anti-immigration laws in 1923 and later committed suicide, citing the trauma caused by that reversal in a suicide note. Bagai, meanwhile, went on to have a successful academic career at MIT, but he couldn’t find employment in the U.S. after graduation and ended up returning to India.

“The Bagai family’s MIT connection really captures the limits of what any one institution can do, even as it’s trying to build something global,” Aiyar says.

Student researchers, guided by Aiyar and supported by the MIT South Asian Alumni Association, also found links between MIT and the decolonization of South Asian countries, with many MIT graduates taking part in nationalist movements throughout the 1930s and 1940s. In 1946, an exhibit created by a British news outlet and displayed at MIT claimed European and Indian soldiers received equal pay in the British army. MIT students mounted a protest against the lie, calling the exhibit colonial propaganda, prompting MIT’s head of libraries to issue an apology.

When India and Pakistan became new nations, their governments considered MIT a partner in their development, resulting in idea exchange and the creation of universities modeled after MIT.

“When India decided to build its Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT), it partnered with a number of countries and a few institutions within the U.S., but ultimately the MIT model won out,” MIT South Asian Alumni Association member Ranu Boppana ’87 says. “There are all these IITs around the country that pretty much follow the same curriculum of MIT and have the same constitution. MIT is very much something they looked to as a beacon, and it’s had a big impact on the global technological revolution.”

America’s civil rights movement also made its way into the exhibit. A poster shows alumni Jaswant Krishnayya SM ’61 and Syed Meer SM ’61 posing with Martin Luther King during the first Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) training session at Morehouse College in Georgia. The training was put on by Indian nationalists.

Even as the exhibit touches on moments of national importance, it ultimately focuses on the stories of individuals. Artefacts on display include a handwritten diary from the first PhD student at MIT, donated to MIT’s Distinctive Collections by his grandson, who is also an MIT alumnus, and reproductions of letters sent home from an early graduate.

Jupneet Singh, an undergraduate who took Aiyar’s class in the spring semester, says her favorite part was learning about the early South Asian women at MIT.

“I think my favorite moment of looking at the archives was looking at the 1968 yearbook and seeing one Indian woman in this sea of white males,” Singh says. “You realize she was such a trailblazer. Studying these people made me realize this is why I’m here — because of these women.”

The exhibit also includes graphs showing the number of South Asian MIT graduates in each decade and a map of North America and South Asia listing the first South Asian MIT graduates from each country.

“The exhibit fills a void because this history is so unknown,” Boppana says. “I think it shapes students’ identity and how they see themselves and how they see the world.”

An idea comes to life

The project was borne when Boppana learned about the first South Asian coming to MIT while reading the book “The Technological Indian.” She reached out to Aiyar in 2019 and expressed the desire to capture stories from older alumni. Aiyar suggested giving students training on conducting oral histories and connecting them with alumni, and Das was able to provide support and connections through MISTI-India.

“This project would look very different if it was just one of us doing it, and I think we’ve learned incredible amounts from each other,” Aiyar says.

Students did research in MIT Libraries’ Distinctive Collection and conducted over 100 oral histories with alumni over the course of the past two Independent Activities Periods and summers. Last semester, Aiyar taught a special subject class, 21H.S04 (MIT South Asian Oral History and Digital Archive Project) to give students designated time to devote to the project.

Aiyar says the class was such a success she’s trying to make something similar a permanent course.

“It’s really been through this project that I’ve been able to share my love of history through this hands-on research with students who have looked at primary sources and archives and built a genealogy of South Asians at MIT out of these — a genealogy in which they locate themselves,” Aiyar says.

The exhibit’s launch on Oct. 14 attracted close to 200 people. The event, held at the Hayden Library and courtyard, was standing room only and included performances by student a cappella group the MIT Ohms, and dance troupes MIT Nritya and MIT Bhangra.

“Watching it come together at the exhibition was a very different experience than the individual research,” says senior Amulya Aluru. “Coming together to watch the videos and looking through the exhibition was like an entire community coming together and supporting South Asians, which I’d honestly never seen before, and it was really inspiring.”

The curators plan to continue their partnership with students as they look to add more content to the exhibit’s digital collection and make it more globally accessible.

“I hope this is only phase one of the project,” Boppana says. “There are other things we want to get to, and we hope people will leave their feedback and engage with us, partner with us, so we can continue to grow the project.”