Media Narratives On Migrants During Covid 19

Report by Srinita Bhattacharjee

Media journalism, the fourth pillar in a democratic setup, plays a fundamental role in making the national population aware of the ongoing socio-economic and political activities by disseminating unbiased information and opinions. But in this era, the media organizations are meted out with acutely significant crises. Sponsored by corporate magnates, the journalistic attitudes have taken a U-turn from accurate reflections on social happenings to focus on business and higher TRPs. The ongoing pandemic has further mirrored the non-neutrality of journalism.

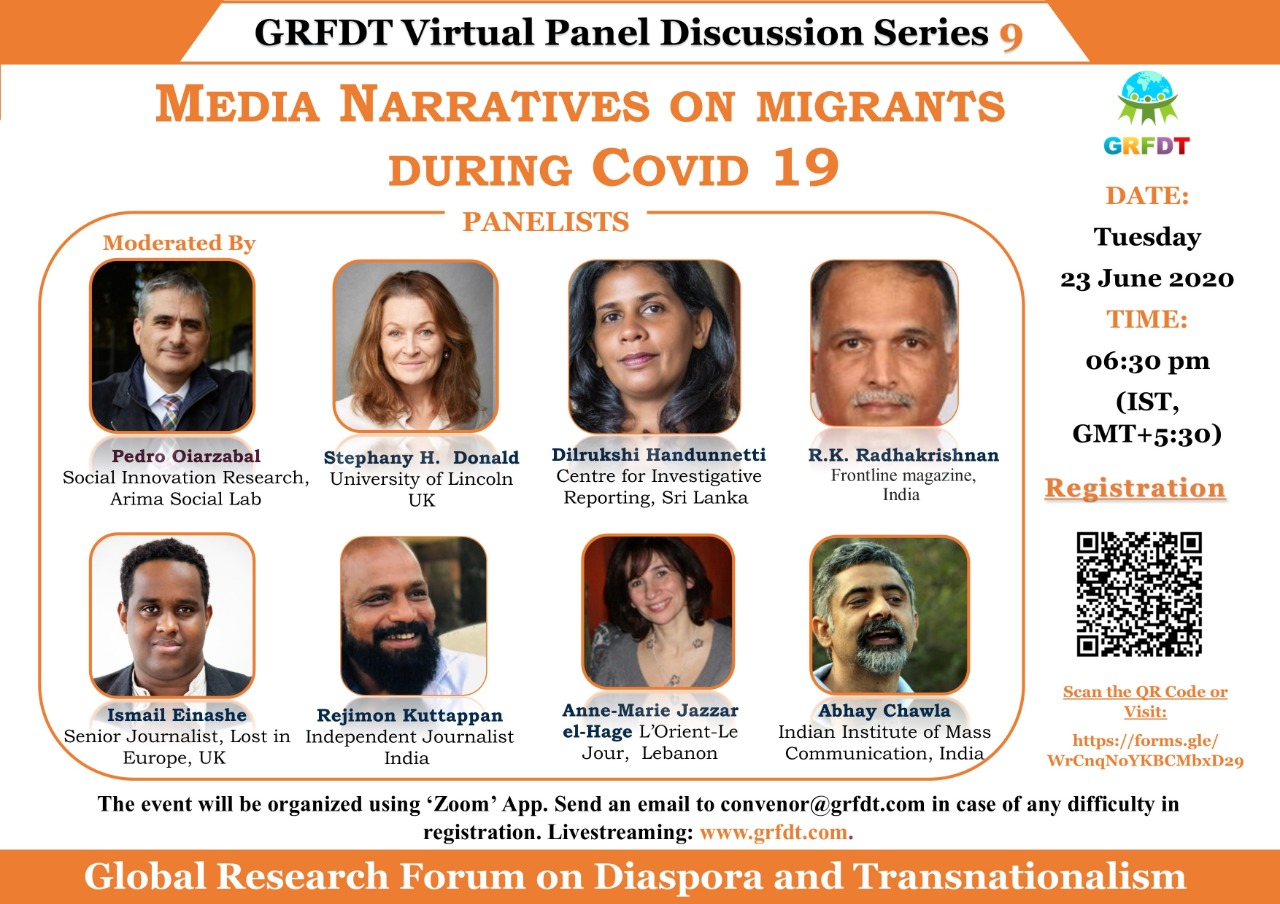

The ninth session in the virtual series of panel discussions conducted by Global Research Forum on Diaspora and Transnationalism (GRFDT) which concluded on 23rd June 2020 witnessed an eclectic amalgam of migration specialists, professionals, academics, and journalists from across the globe deliberating on its core theme- ‘Media Narratives on Migrants during Covid19’. Moderated by Dr. Pedro Oiarzabal, Director, Social Innovation Research, Arima Social Lab, the illustrious panellists broadly discoursed upon two kinds of media narratives that are functioning during the pandemic. One is relatively democratic, promoting news based on facts conditioning the migrants and the other conservative media, which keeping in tune with the tradition, have highlighted migrants as carriers of the virus and hence demanded their ostracization.

The first speaker of the evening, Prof. Stephany H. Donald, University of Lincoln, UK drew the scenario of her country. Quoting from the popular British print media narratives, she revealed the racialized media portrayals of migrants whose presence within the national perimeters is considered an imminent threat to the nation-state and its citizen nationals. Even during the COVID crisis, leading British dailies have projected migrant workers in poor light, although, most of the frontline workers in the UK are migrants. COVID has been used as a trope to create fear among the citizens and as an excuse to push borders keeping the migrants away. The government has also deployed this idea in dishonest ways to create a colonial perspective of the migrant. But simultaneously, there has been a narrative around the key workers whose relentless contribution towards British society during the pandemic, was rarely reported by British tabloids.

The deliberation then moved to South Asia with Ms. Dilrukshi Handunnetti, Executive Director, Centre for Investigative Reporting, Sri Lanka, and Mr. R. K. Radhakrishnan, Associate Editor, Frontline Magazine, India, pitching on the media narratives on migrants in Sri Lanka and India respectively. Ms. Handunnetti clearly stated the ironic portrayals of migrants by the national media during the pandemic. Sri Lanka, which is a remittance-based economy, has millions of its population engaged as low and unskilled labour in the Gulf countries, a majority among them being women domestic labour. Also, this is the only country in South Asia with a legislated return migration policy even then, the returnees are stigmatized and discriminated against instead of being provided with a secure haven and other provisions for sustenance. They are painted as COVID bombs to generate fear among the citizens. A holistic reintegration measure is out of sight while generalized discriminatory narratives are in full swing.

Mr. Radhakrishnan contended that the Indian media that heavily invested in the internal migrants and their arduous journeys back to villages, blaming the government for not addressing their problems, remained tone-deaf towards the similar plights faced by the less skilled and undocumented Indian migrant workers in the Gulf countries. Although India had facilitated the repatriation process, it came with a hefty price, unaffordable for migrants who have gone out of work and remunerations. For migrants who have overstayed their visa permits due to the worldwide lockdown and have become undocumented or illegals, leaving the host country was the only option. The mainstream media hardly covered their ardent pleas of return.

Ms. Anne-Marie Jazzar el-Hage, journalist, L’Orient-Le Jour, Lebanon presented two variants of media reporting from her country. The conservative media continued to paint a negative picture of the migrant as replacing citizens in job sectors and as potential virus conveyor in the context of the ongoing crisis. This kind of traditional parochial portrayal has further led to abusive measures inflicted upon low skilled migrants who are not protected by the labour laws of Lebanon. But the new media rallied for the social justice of these disenfranchised immigrants, denounced the kefala system or modern-day slavery that gives all the rights to the employers, campaigned against human rights violations, and the reiterating hate speeches. They are helping prevent panic by amplifying the voices of those affected and mitigate the social and economic costs for the people and societies in which they work. Ms. Hage is enthusiastic that a section of journalists still provides relevant information by refraining from speaking on behalf of the migrants and instead served as a mediator so that the migrant voices reach the government and pressurize them to implement favourable actions and policies.

The next speaker, Ismail Einashe, Senior Journalist, Lost in Europe, UK, concurs that the pandemic has shown how migrants indeed survive on the marginalized position globally. In the next few minutes, he clarifies how media framing is having an impact on the disenfranchised migrants with the EU borders and entry points closed for an indefinite period. The narratives on migrants framed by the media houses in several countries of the European Union are biased and xenophobic, the long-standing tropes of typically portraying migrants as threats to the nation-states since the migrant crisis of 2015. COVID has allowed the media to spread fake news and rumours constructed to display migrants as carriers of the disease accentuating racist attacks on them. Einashe reports that during this pandemic with the sudden closure of borders, most migrants are stuck on the routes as well as entry points not able to move forward or return home because the world has come to a standstill. He quotes the IOM in stating that these migrants exposed to exploitation, abuse, and stigmatization are further rendered deplorable in detention camps. Many right-wing governments in the EU like Greece and Austria are using the threat of COVID to further their own agenda on enacting strict border policies, to the extent of dissolving the rights to asylum in the latter case. The kind of anti-migrant propaganda strewn across by media framings have further marginalized them.

Dr. Abhay Chawla, Indian Institute of Mass Communication, India, made the final topical speculations of the evening. He exposed the structural hypocrisies characterizing the mainstream Indian media that garnered applause for reporting the sad plights of the rural migrants during COVID. Further scrutiny revealed that an oft- repetitive image of a migrant was in circulation with different hyperbolized versions of the same story. Of course, the media narratives did bring to the fore the migrant lives that are usually glossed over. But these reports are not substantiated with profound evidence. Apart from a few exceptions, most media stories are mere concoctions of random elements extracted from narratives of other media organizations. In many cases, Dr. Chawla contends, that the news was churned out inside the newsroom and hence was ignorant of the ground realities. They displayed the journalistic perspective instead of the migrant and their real journey.

The six discourses received insightful reflections from esteemed scholars on migration. While Prof. Kamala Ganesh pronounced the missing ‘class’ element from the media narratives, Prof. Binod Khadria lauded the constructive efforts of the national media in shifting our focus from the elite diaspora abroad to the neglected plights of the internally displaced labour migrants in India and also lamented the absence of caricaturing humour from mainstream media today. Prof. C. S. Bhat, however, holds media framings responsible for highlighting the perishable conditions engendered by COVID that migrants are unlikely to survive.

An engaging and interactive session as it was, the audience posted several queries too. The main concern was around how journalism could be done ethically in terms of reporting real issues. Mr. Shabari Nair linked this concern to the tone and vocabularies used in the media circle to create fissures of binaries to which Mr. Radhakrishnan stated that democratic mode of news reporting requires tools which journalists are not well equipped. Moreover, the field reporters had FIRs filed in their names and several dispossessed with viral infections while ethically focussing on real issues. With a sharp increase of attacks on journalistic freedom, media organizations should innovate ways of connecting and informing a wider audience.

Global instances of outstanding public-service journalism are plenty, so are the constraints. While clarity and accuracy in reporting can save lives, the government must amend laws in favour of journalism. Einashe opined that high-quality information requires business models for sustenance. The global economic collapse has severely reduced the advertising revenues that many media outlets depend. Worldwide, countless independent news providers are compelled to scale down, lay off reporters, or close altogether. The COVID crisis has proven challenging in terms of media reporting. Apart from a few courageous exceptions, critical voices are barred, thereby restricting the media from playing its democratic role in society. An independent media is the need of the hour that can serve as a platform in the public sphere.

Report by Srinita Bhattacharjee, University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad, India, Email: [email protected]