Neighborhood Assets Linked to Reduced Hopelessness in Youth, Pitt-UPMC Study Finds

Youth living in neighborhoods with more community assets — such as parks, libraries, health services and transportation options — were less likely to report feelings of hopelessness, according to a new JAMA Network Open study from the University of Pittsburgh and UPMC.

“Rather than looking at deficits, we took a strengths-based approach to identify bright spots in communities and neighborhoods where young people live and play that actually bolster mental health,” said lead author Nicholas Szoko, M.D., Ph.D., assistant professor of pediatrics at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, who did this research as a postdoctoral fellow at the Pitt School of Medicine and UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. “This research helps us understand how we can best honor those strengths and elevate the important work that is happening in communities to support young people’s mental health.”

According to the 2023 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 40% of U.S. adolescents have experienced feelings of hopelessness, one in five have contemplated suicide and almost one in 10 have attempted suicide.

“The number of young people experiencing mental health challenges is staggering,” said senior author Alison Culyba, M.D., Ph.D., M.P.H., associate professor of pediatrics, public health, and clinical and translational science at Pitt and UPMC Children’s. “Young people are struggling, and the root causes are complex. We need to look beyond the individual and focus on what we can do as a society to ensure the health and wellbeing of youth in our region.”

To understand how community assets contribute to mental health of adolescents in Pittsburgh and Allegheny County, the researchers used a western Pennsylvania database of community assets in eight categories: transportation, education, parks and recreation, faith-based entities, health services, food resources, personal care services such as salons and barbershops, and social hubs such as family support centers, libraries and community organizations.

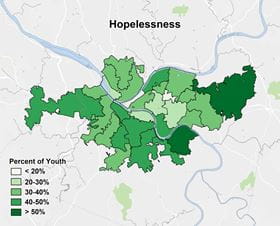

They compared the density of assets for each zip code with three mental health measures — feelings of hopelessness, non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal ideation — reported by Allegheny County high school students in the 2018 Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

While community asset density was not linked with non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal ideation, the researchers found that youth who lived in areas with a higher density of certain asset types were less likely to report hopelessness.

“When we think about hopelessness, it’s important to think about the opposite of that, too: hopefulness and future orientation, which is having plans and goals for the future,” said Culyba. “We know that hopefulness is really important for a young person’s overall health and wellbeing.”

The analysis identified educational assets like preschool centers and elementary schools, transportation assets including bus stops, park and rides and light rail stations, and health assets such as outpatient clinics, hospitals and dentist offices as protective against hopelessness.

The relationships between community asset density and hopelessness persisted after accounting for other factors that could contribute to mental health via incorporation of the Child Opportunity Index into analyses. This standardized metric includes a broad range of neighborhood features such as rates of poverty, unemployment and high school graduation.

“When we directly compared the Child Opportunity Index with asset density, we found that they were not consistently correlated as we might expect,” said Szoko. “Areas with high poverty did not always have low asset density and vice versa, which says to me that community strength and vitality is something different than the absence of challenges.”

While asset density overall was linked with lower rates of hopelessness, some zip codes bucked the trend.

“We found that some communities with fewer community assets had better than expected mental health measures,” said Szoko. “To me, this says that we are only measuring a small piece of the puzzle, that there are other strengths and assets that are buffering against negative mental health that we haven’t recognized on the academic side yet.”

As part of their research to better understand community strengths they might be missing, Culyba, Szoko and their team are partnering with communities and young people to learn what resources and spaces in their neighborhoods matter most to them.

And measuring these strengths is just the first step, said Culyba.

“This work is exciting to me because we can really map out at a hyper-local level the neighborhoods that are rich in certain resources and others that may have fewer because of historical issues around disinvestment,” she said. “We hope to create a spotlight where we can activate as a larger community around how to best create and support investment in those assets where they don’t exist now, so we can make sure that young people, regardless of where they live, have access to the resources and supports that they deserve.”

Other authors on the study were Aniruddh Ajith of Pitt and Kristen Kurland of Carnegie Mellon University.