New Compound Discovery Shows Potential For Certain Parasitic Diseases

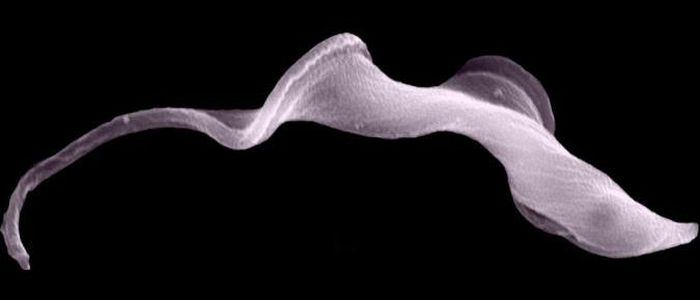

Scientists have discovered a new class of compound that is potentially active against trypanosome parasites that cause human African trypanosomiasis (or sleeping sickness) and Chagas disease.

The ground-breaking findings – published in the journal Science and led by researchers at the University of Glasgow and Novartis Global Health (formerly Novartis Institutes for Tropical Diseases) – reveal potent compounds discovered for the two separate types of trypanosomiases, showing potential for development as new medicines for these diseases.

The study demonstrated that the compounds were able to cure a mouse model of sleeping sickness with just a single dose, and a short course of daily doses across five days cured Chagas disease in the same models.

African trypanosomiasis (or sleeping sickness) is a major killer disease which puts around 70 million people at risk in sub-Saharan African countries and is invariably fatal if untreated or inadequately treated. Meanwhile, around seven million people are currently infected by Chagas disease, which can cause irreversible damage to the heart and digestive tract.

There are currently no drugs available that effectively cure Chagas disease; while for sleeping sickness, there have been some steps forward toward new therapies in recent years.

The researchers also show in the study exactly how the compounds, called cyanotriazoles (or CTs for short), kill parasites without adversely affecting host cells. These compounds selectively bind to a parasite enzyme (called topoisomerase II) that is essential for the replication and maintenance of DNA, which carries the genetic blueprint vital for life. By binding to and inhibiting this enzyme, the compounds introduce breaks into the DNA that are lethal to the parasites.

The Glasgow group – led by Professor Mike Barrett from the Wellcome Centre for Integrative Parasitology in the University’s School of infection & Immunity – made inroads into finding that mechanism of action using a technique known as metabolomics, through the Glasgow Polyomics facility, which showed how DNA was being degraded in the cells. Parasites resistant to the drugs had changed their topoisomerase protein structure such that they no longer bound the drug.

The Novartis team, led by Srini Rao, worked out the three-dimensional structure of the trypanosome’s topoisomerase, revealing how CTs bind to a particular part of the trypanosome’s enzyme that is absent from the human version.

Mike Barrett, Professor of Biochemical Parasitology at the University of Glasgow, said: “Compounds with this degree of potency, working through a newly discovered mechanism, represent a major breakthrough. If they are proven to be safe in humans and retain the levels of activity seen in mice, they could offer the first effective therapy of Chagas disease which afflicts millions of people in Latin America.”

The paper, ‘Cyanotriazoles are selective topoisomerase II poisons that rapidly cure trypanosome infections,’ is published in Science. The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust.