New study could help unlock ‘game-changing’ batteries for electric vehicles and aviation

Li-SSBs are distinct from other batteries because they replace the flammable liquid electrolyte in conventional batteries with a solid electrolyte and use lithium metal as the anode (negative electrode). The use of the solid electrolyte improves the safety, and the use of lithium metal means more energy can be stored. A critical challenge with Li-SSBs, however, is that they are prone to short circuit when charging due to the growth of ‘dendrites’: filaments of lithium metal that crack through the ceramic electrolyte. As part of the Faraday Institution’s SOLBAT project, researchers from the University of Oxford’s Departments of Materials, Chemistry and Engineering Science, have led a series of in-depth investigations to understand more about how this short-circuiting happens.

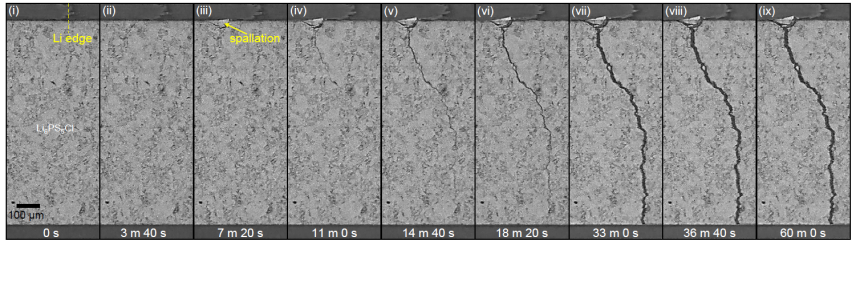

In this latest study, the group used an advanced imaging technique called X-ray computed tomography at Diamond Light Source to visualise dendrite failure in unprecedented detail during the charging process. The new imaging study revealed that the initiation and propagation of the dendrite cracks are separate processes, driven by distinct underlying mechanisms. Dendrite cracks initiate when lithium accumulates in sub-surface pores. When the pores become full, further charging of the battery increases the pressure, leading to cracking. In contrast, propagation occurs with lithium only partially filling the crack, through a wedge-opening mechanism which drives the crack open from the rear.

This new understanding points the way forward to overcoming the technological challenges of Li-SSBs. Dominic Melvin said: ‘For instance, while pressure at the lithium anode can be good to avoid gaps developing at the interface with the solid electrolyte on discharge, our results demonstrate that too much pressure can be detrimental, making dendrite propagation and short-circuit on charging more likely.’

Sir Peter Bruce, Wolfson Chair, Professor of Materials at the University of Oxford, Chief Scientist of the Faraday Institution, and corresponding author of the study, said: ‘The process by which a soft metal such as lithium can penetrate a highly dense hard ceramic electrolyte has proved challenging to understand with many important contributions by excellent scientists around the world. We hope the additional insights we have gained will help the progress of solid-state battery research towards a practical device.’

According to a recent report by the Faraday Institution, SSBs may satisfy 50% of global demand for batteries in consumer electronics, 30% in transportation, and over 10% in aircraft by 2040.

Professor Pam Thomas, CEO, Faraday Institution, said: ‘SOLBAT researchers continue to develop a mechanistic understanding of solid-state battery failure – one hurdle that needs to be overcome before high-power batteries with commercially relevant performance could be realised for automotive applications. The project is informing strategies that cell manufacturers might use to avoid cell failure for this technology. This application-inspired research is a prime example of the type of scientific advances that the Faraday Institution was set up to drive.’

The study ‘Dendrite initiation and propagation in lithium metal solid-state batteries’ has been published in Nature.