New Study Reveals Greenland Acts as Methane Sink, Contrary to Previous Assumptions

It has long been thought that the Arctic may be a ticking climate bomb. As local temperatures rise and permafrost thaws, more and more of the greenhouse gas methane is released. But in a new study from the Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management at the University of Copenhagen, researchers have been able to conclude that at least Greenland does not seem to be a methane bomb after all.

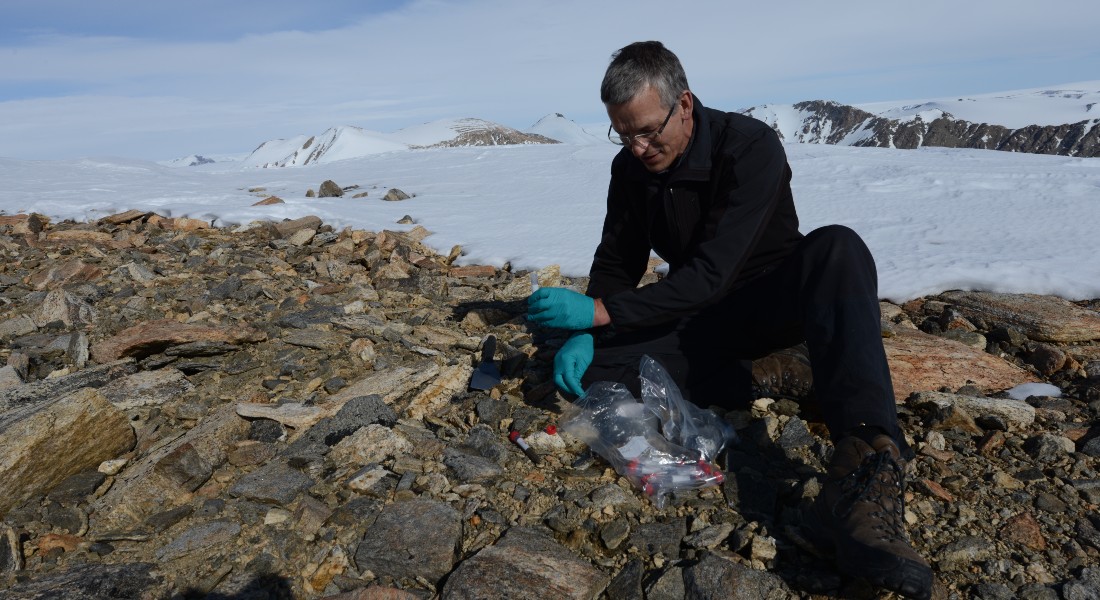

In fact, Greenland consumes more methane than it releases, according to analyses of soil samples from eleven areas across Greenland. The researchers used an existing dynamic methane model, which made it possible to quantify the methane budget for all of Greenland.

The researchers have been able to conclude that, on average and since 2000, dry landscapes of the ice-free part of Greenland have consumed more than 65,000 tons of methane annually from the atmosphere, while 9,000 tons of methane have been released annually from its wet areas.

“This is partly due to Greenland’s widespread dry landscapes, where methane from the atmosphere is consumed into the upper layers of soil, and partly because the ice-free parts of Greenland have only been without ice since the last ice age, meaning that they never stored much carbon, which could lead to large methane emissions, as can be measured elsewhere in the Arctic,” says Professor Bo Elberling, who led the study.

The research is published in the scientific journal Nature Communications Earth & Environment.

Microorganisms make methane uptake possible

The absorption of methane is made possible by a unique group of microorganisms that typically live in the upper half meter of arctic soil, where it is dry and oxygen is present. These microorganisms use methane that penetrates the soil from the atmosphere and convert it into carbon dioxide.

While carbon dioxide is also a well-known greenhouse gas, its greenhouse gas effect is a lot less strong than methane, making the conversion of methane to carbon dioxide good climate news.

The study also provide knowledge about the optimal soil conditions for methane uptake in the Arctic. This is because the microorganisms require various nutrients and a soil with just the right acidity (pH-level). Researcher and first author of the article Ludovica D’Imperio elaborates:

“Our work also sheds light on the conditions that, in addition to the climate, are crucial for methane uptake in Greenland. Based on our statistical model, we can conclude that it depends on the presence of the right microorganisms, soil acidity and copper – knowledge that we were previously uncertain about,” she explains.

Greenland’s methane budget

All in all, the new study demonstrates that Greenland contributes with a small uptake of methane under current conditions, which will most likely increase as Greenland’s climate will change in the future.

However, the conclusion is not that Greenland will impact the total global amount of atmospheric methane or prove to be decisive for Arctic methane budgets. The uptake of methane in Greenland is simply too small compared to other known methane sources, both in the Arctic and globally.

Indeed, the majority of Arctic wetlands, and thus the largest natural source of methane, are in Siberia. Until the war between Russia and Ukraine broke out, the Danish researchers conducted studies there alongside German and Dutch counterparts.

“We had just managed to demonstrate that methane uptake occurs in dry Siberian soils as well, but more studies will be needed in Siberia to provide a methane budget similar to what we now have for Greenland. Still, we have advanced considerably with similar studies in cold regions in Tibet, for example, where measurements indicate a similar conclusion as for Greenland. But the work has only just begun to understand the variation in this uptake of methane and its significance for the global methane budget,” says Elberling.

According to the researchers, the new study does not change the fact that greenhouse gas emissions from human activities must continue to be reduced. But the study does contribute previously unknown nuances of Greenland’s natural methane budget.

“Our research and that of others in the field helps to increase our understanding of the complex processes that are critical for the global methane budget. The budgets will be used both now and in the future to develop models that can provide a more accurate picture of the significance of global methane uptake,” concludes Bo Elberling.