New Study Reveals Link Between Historical Housing Discrimination and Shortfalls in Colon Cancer Treatment

A nationwide study of 196 cities shows that housing discrimination from 90 years ago still casts a historical shadow of inequities in colon cancer care today, S.M. Qasim Hussaini, M.D., of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and colleagues at the American Cancer Society and Johns Hopkins School of Public Health report in the journal JCO Oncology Practice.

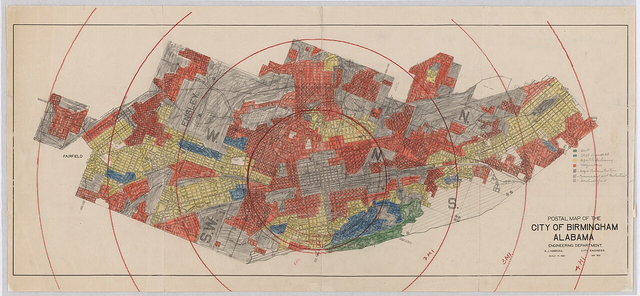

In the 1930s, the federally sponsored Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, or HOLC, used racial composition to map out residential areas worthy of receiving mortgage loans and those areas to avoid. Neighborhoods high in Black, immigrant or minority non-white populations were red-lined as hazardous for home loans, creating systemic and persistent disinvestment in those neighborhoods, along with wealth inequities and concentration of health-harming exposures and psychosocial stressors. These limitations reduced access to health-promoting goods and resources such as green space, parks and healthy foods in redlined neighborhoods.

To test whether residence in the formerly red-lined neighborhoods is associated with poorer guideline-concordant cancer care today, Hussaini and colleagues mapped colon cancer care for 149,917 newly diagnosed colon cancer patients from 2007 through 2017, as detailed in the National Cancer Database, against current-day residence in one of the four historical HOLC mapping areas. In the 1930s, the green HOLC areas, or HOLC A, were considered best for mortgage loans; the blue areas, or HOLC B, were considered still desirable; the yellow areas, or HOLC C, were marked as definitely declining; and the red areas, or HOLC D, were flagged as hazardous and to be avoided for mortgage lending purposes.

Overall, the researchers found that individuals diagnosed with colon cancer who resided in previously redlined HOLC D areas across the United States were today more likely to be diagnosed with advanced-stage disease, were less likely to receive guideline-concordant or timely treatment, and had worse survival.

“These findings underscore the long shadow of institutional racism through state- and federal-level discriminatory practices in shaping access to high-quality care and better outcomes for colon cancer, which is amenable to early detection and treatment,” said Hussaini, an assistant professor in the UAB Department of Medicine Division of Hematology and Oncology.

In detail, individuals living in HOLC D areas were more likely to be diagnosed with late-stage colon cancer compared with those living in HOLC A areas. Of the 78,164 people who did not receive guideline-concordant care as defined by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the odds of receiving non-guideline concordant care increased for individuals residing in areas with increasing hazard grades assigned by HOLC B, HOLC C and HOLC D, as compared with individuals residing in HOLC A areas.

A predicted probabilities model — which adjusts estimates of guideline non-concordance for age and sex — showed that non-receipt of guideline-concordant care overall, as well as non-receipt of guideline-concordant surgery, lymph node evaluation and chemotherapy, sequentially increased from the HOLC A areas through to the HOLC D areas. Compared with those cancer patients living in HOLC A areas, those residing in HOLC B, HOLC C and HOLC D areas had increased wait times to the start of adjuvant chemotherapy. Adjuvant chemotherapy is given after surgery in order to kill any remaining cancer cells and reduce the chance of disease recurrence.

Compared with newly diagnosed colon cancer patients residing in HOLC A areas, those living HOLC C and D areas had 9 percent and 13 percent excess risk of death in statistical models that did not adjust for stage of the cancer at time of diagnosis. After stratification by stage — either early, stages I and II, or advanced, stages III and IV — the excess risk of death association persisted for the HOLC C and HOLC D areas for both the early and late stages at diagnosis.

Several previous studies by others have noted racial or ethnic disparities in breast cancer outcomes in previously redlined neighborhoods in New Jersey, an increased incidence of advanced-stage lung cancer in formerly redlined areas of Massachusetts and a lower odds of lung cancer screening for Black individuals in previously redlined areas of Boston. However, those single geographic area studies did not examine whether patients received quality cancer care.

“To our knowledge, this is the first national study, including all states, to evaluate the association between historical institutional racism and current-day receipt of quality cancer care and outcomes using standardized measures of cancer diagnosis, individual and tumor characteristics, receipt of treatment, and survival,” Hussaini said. “Other strengths of the study are a diverse study population including all age and racial groups, and a focus on multiple aspects of care from stage at diagnosis to treatment receipt and survival.”

The American Society of Clinical Oncology, or ASCO, defines health equity as a fair and just opportunity for everyone to be as healthy as possible. Colon cancer has about 150,000 new cases each year. It is the third most diagnosed cancer in the United States and the second leading cause of death from cancer, even though colon cancer is amenable to early detection and treatment. Widespread inequities in survival exist due to unequal access to care.

Co-authors with Hussaini in the study, “Association of historical housing discrimination and colon cancer treatment and outcomes in the United States,” are Qinjin Fan, K. Robin Yabroff and Leticia M. Nogueira, the American Cancer Society, Atlanta, Georgia; and Lauren C.J. Barrow and Craig E. Pollack, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.