Princeton researchers at forefront of national plans for technological and social transition to net-zero emissions

On Feb. 2, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine published the interactive report, “Accelerating Decarbonization of the U.S. Energy System,” which provides a technical blueprint and policy manual for the first decade of a wholesale transformation of the American economy to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

Princeton scientists and research played a critical role in a new report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine that investigates the technology, policy and societal dimensions of accelerating decarbonization in the United States.

The report was conducted by a nationwide committee of experts chaired by Stephen Pacala, the Frederick D. Petrie Professor in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, and including Jesse Jenkins, assistant professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering and the Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment.

In a public briefing about the announcement, Pacala said that the National Academies’ report is unique for its focus on creating a “fair and equitable path to net-zero by 2050.”

“What distinguishes this report is its focus on societal factors,” said Pacala, who directs the Carbon Mitigation Initiative (CMI) based in Princeton’s High Meadows Environmental Institute (HMEI). “At least half of what we recommend are targeting the social dimensions of this challenge.”

The National Academies’ report puts — for the second time in two months — the work of Princeton researchers at the forefront of a re-energized national conversation about converting the American energy sector to net-zero emissions by midcentury.

The report extensively quotes the Princeton study, “Net-Zero America: Potential Pathways, Infrastructure and Impacts,” a landmark report by faculty and researchers affiliated with HMEI and the Andlinger Center that provides a highly detailed and achievable blueprint for achieving a carbon-neutral economy in the United States by 2050. Net-Zero America has been a focus of CMI for nearly two years and is an ongoing project.

Widely reported on in national media, the Net-Zero America study has been held up as a comprehensive guide for realizing President Joseph R. Biden’s commitment to eliminating the nation’s net-greenhouse gas emissions — meaning the country does not produce more carbon dioxide or other greenhouse gases than can be removed from the atmosphere by nature or technology — in the next 30 years and preventing the worst effects of climate change.

“Princeton’s goal with Net-Zero America and the goal of the National Academies report are very similar,” Pacala said. “We wanted to provide the public with actionable information based on the latest science and social science.”

Net-Zero America was one of several studies reviewed by the expert committee when writing the National Academies report, but the Princeton study was the most comprehensive, Jenkins said.

“Preliminary findings from the Princeton Net-Zero America study were invaluable in shaping the committee’s view on what needs to be done to get the nation on track for net-zero by 2050, as well as in focusing the committee’s deliberations on how to get things done, including the suite of policy recommendations that is the National Academies report’s main contribution to the public discourse,” Jenkins said.

The Net-Zero America study outlines five distinct pathways that could decarbonize the entire U.S. economy over the next 30 years, using existing technology and at costs aligned with historical spending on energy. The research is the first to describe at a high degree of granularity (at a state-by-state level or better) what needs to be built — and when and where — across key sectors. It also is the first to provide comprehensive models of the resulting costs, changes to the job market, implications for the energy sector, and impacts on air pollution and public health for each state, sometimes down to the county.

“You can think of the Net-Zero America study as the most technologically sophisticated blueprint on how a nation would build a clean-energy system,” Pacala said. If Net-Zero America is a technological blueprint, the National Academies’ report is its essential companion, a “technical and social blueprint with a policy manual,” he said.

“The social dimensions are absolutely essential,” Pacala said. “At the end of the day, we have to maintain public support for a transition of the entire energy sector through three decades, and that means we’re really going to have to pay attention to people and ensure a fair distribution of both costs and benefits.”

Specifically, the National Academies report provides policy recommendations and public entities such as the creation of a national “green bank” that would invest in infrastructure, education and retraining, and clean-energy-related manufacturing in communities and regions — such as the coalfields of Appalachia — that would be affected by the transition away from a carbon-based economy.

The National Academies’ report reiterates the fact that converting the economy to clean and renewable energy is not only already technologically possible, but in fact much cheaper than “business as usual,” Pacala said. The technological and operational costs of wind and solar energy have plummeted in recent decades — largely due to proactive support from public policy — and operators would be relieved of the need to constantly procure fuel as they would for coal or natural gas.

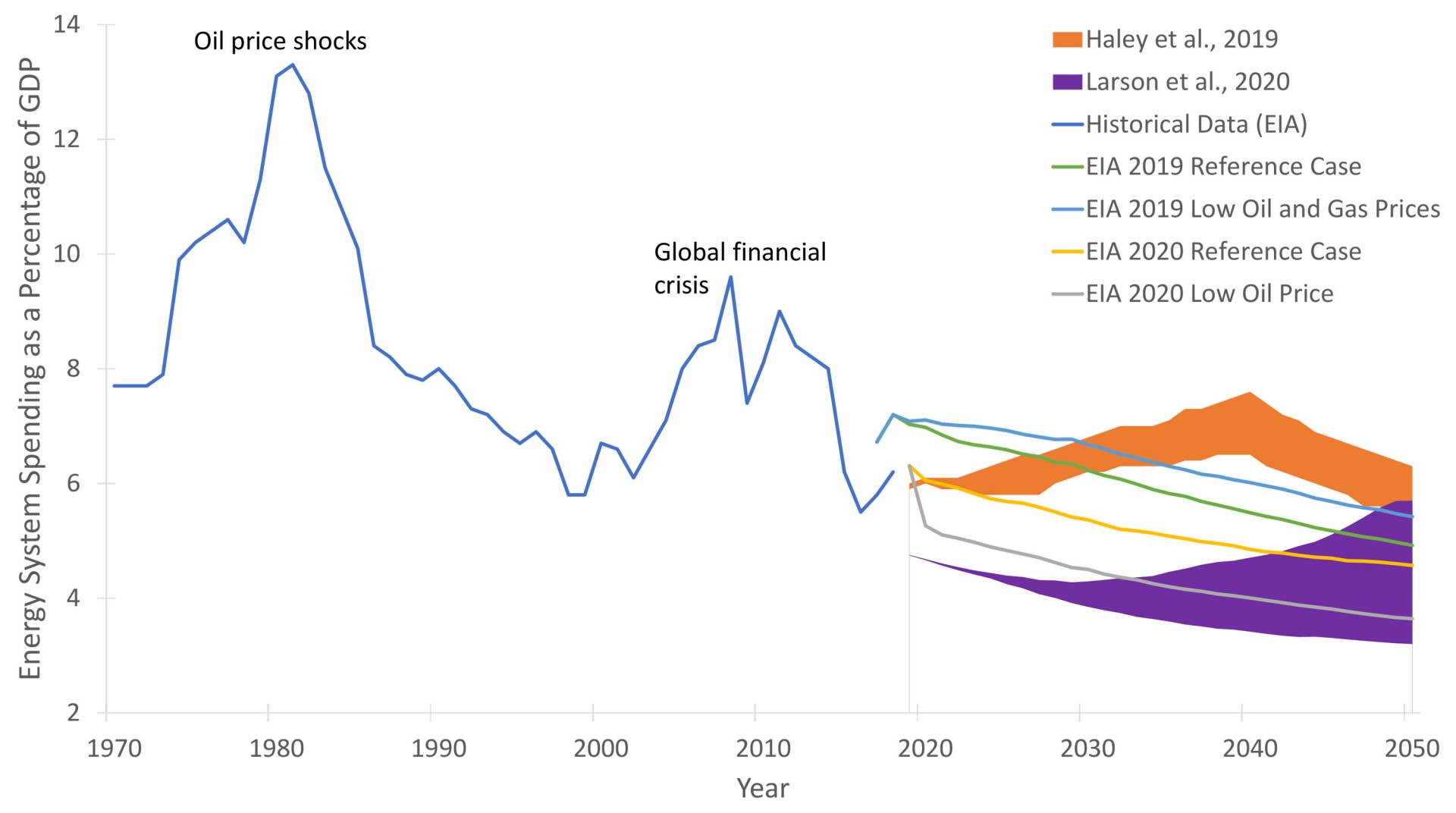

The interactive report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine demonstrates that converting the American economy to clean and renewable energy by 2050 is not only already technologically possible, but in fact much cheaper than “business as usual.” This graph shows historical energy system costs as a percentage of the gross domestic product (left). To the right are the ranges for projected energy-system costs under two different net-zero studies — Princeton’s Net-Zero America (purple) and the Evolved Energy Research (orange), with the ranges set by each study’s highest- and lowest-cost scenarios — and four projections from the federal Energy Information Administration. The expert committee that produced the National Academies report concluded that the transition to net-zero requires spending less than what the United States has spent on energy in the past 30 years.

“Once you’ve built the wind and solar infrastructure, you don’t have to pay for fossil fuel to create electricity. The fuel is in fact free,” Pacala said during the National Academies public briefing. “The transition to net-zero requires spending less than what we’ve spent on energy in the past 30 years.”

The National Academies’ report emphasizes that investing now in emerging energy technology is essential to carrying the net-zero transformation beyond 2030, Jenkins said. If future costs skyrocket because the technology is prohibitively expensive, the transition to net-zero will become economically and socially disruptive. “We lay out that the other task for this decade is to take the range of technologies that we know we’ll need beyond 2030, and do the same thing we did for today’s technology — make them cheap and ready for rapid scale-up,” he said.

During the public briefing, Pacala addressed questions regarding the 30-year time frame for decarbonizing the American economy while the climate change is accelerating now. He said that 30 years is the benchmark scientists and policymakers have adopted.

A more rapid conversion, Pacala said in a separate interview, would not only create greater economic and social upheaval, but also require a prolonged and unfeasible mobilization of technology and workforce on the scale of World War II. Instead, the United States and the world need to concurrently focus on replenishing carbon sinks such as forests and wetlands, while also protecting — or preparing to evacuate — low-lying areas threatened by sea level rise.

“We’re balancing harms on all sides now, and we think this 30-year transition is the sweet spot that minimizes these harms across the board,” Pacala said.

“Carbon dioxide is extremely dangerous — it’s causing extreme weather now, it’s hurting people now. Every bit we add is worse than the bit we added before,” he said. “We put the poison in the atmosphere and now we have to make adaptions. We need to harden our infrastructure and change our patterns of coastal development, while we also work to eliminate our carbon emissions over the next 30 years.”

CMI will continue working on Net-Zero America and building on the momentum of the National Academies report by significantly developing the models and simulations needed to rollout a new energy infrastructure, Pacala said. Specifically, he would like to expand the models so that they combine energy emissions with natural carbon sinks and the mitigation of non-carbon greenhouse gases such as methane.

The computational and modeling knowledge and resources available at Princeton through Princeton Research Computing, the High-Performance Computing Research Center and the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (administered by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) position the University as a potential leader in optimizing the implementation of net-zero energy infrastructures in the United States and other countries, Pacala said.

“We plan on breaking through the computational barriers and democratizing this kind of planning to make it possible for anyone to do a net-zero study,” he said. “There’s a bleeding-edge technical computer science problem that we need to crack now, and Princeton can do that.”

At the same time, Jenkins said, his lab will focus on using the Net-Zero America study’s five pathways as benchmarks to evaluate the effectiveness of forthcoming federal policies at getting the United States on track to net-zero emissions.