Promising Results: Personalized Vaccine for Liver Cancer Demonstrates Effectiveness in Clinical Trial

Adding a personalized anti-tumor vaccine to standard immunotherapy is safe and about twice as likely to shrink cancer as standard immunotherapy alone for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, the most common type of liver cancer, according to a clinical trial led by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and its Convergence Institute.

The study will be published April 7 in Nature Medicine, with findings also presented at 1:30 p.m. PT at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths worldwide. Fewer than one in 10 patients survive five years post-diagnosis. Existing immune therapies such as PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitors, aimed at releasing restraints cancer cells place on the immune system, have limited effects.

A preliminary clinical trial led by Kimmel Cancer Center investigators shows that adding a personalized anti-tumor vaccine to PD-1 inhibitor therapy may improve patient outcomes. The study enrolled 36 patients with HCC. All patients received the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab in combination with a personalized anti-tumor vaccine. The most common adverse effect associated with the vaccine was mild injection site reactions. There were no serious adverse events. Nearly one-third of the patients treated with the combination therapy saw their tumors shrink—about twice as many patients as seen in studies of anti-PD-1 therapy alone in HCC. About 8% had a complete response with no evidence of tumor left after the combination treatment.

“The study provides evidence that a personalized cancer vaccine can enhance clinical responses to anti-PD-1 therapy,” says lead author Mark Yarchoan, M.D., an associate professor of oncology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “A larger randomized clinical trial will be needed to confirm this finding, but the results are incredibly exciting.”

Decades of experience and research with cancer vaccines from study co-author Elizabeth Jaffee, M.D., deputy director of the Kimmel Cancer Center and the Dana and Albert “Cubby” Broccoli Professor of Oncology, and other visionary Johns Hopkins scientists have made the successful trial possible. Jaffee and her colleagues saw the potential of cancer vaccines early on and worked to overcome challenges to their development.

“We are at an exciting time in new therapy development. Personalized vaccines are the next generation of vaccines that are showing promise in treating difficult cancers when given with immune checkpoint therapy. Our Cancer Convergence Institute provided technology and computational tools to make the analyses possible,” says Jaffee, who is also director of the Convergence Institute.

To make personalized cancer vaccines, scientists take tumor biopsy cells to identify cancer-associated genetic mutations in the tumor. The scientists use a computer algorithm to determine which of the mutated genes produce proteins the immune system can recognize. Then, scientists manufacture a personalized vaccine containing the DNA for the selected mutated genes. Each vaccine may include up to 40 genes. The vaccine helps the immune system recognize the abnormal proteins encoded in the selected genes and destroy cells producing them.

Combining the personalized vaccine with the PD-1 inhibitor provides a one-two punch to the tumor. The PD-1 inhibitor helps revive immune cells, called T-cells, in the tumor that have become exhausted and unable to destroy the tumor cells. The personalized vaccine calls in the cavalry, helping recruit a fresh set of T-cells that target the specific mutant proteins in the tumor.

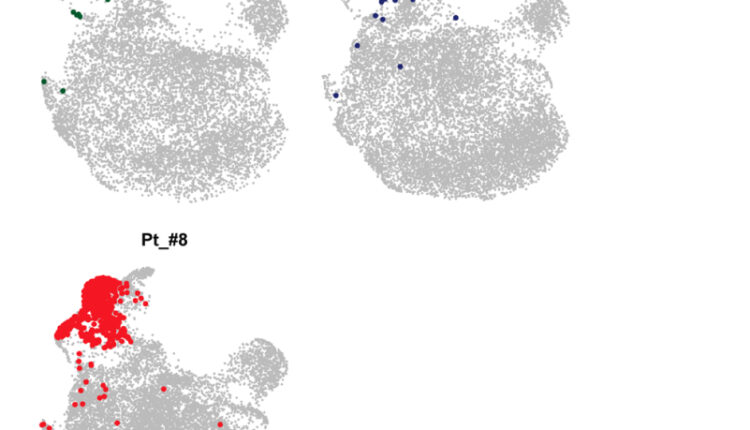

When the research team evaluated tumor biopsy samples taken from the study participants after they received the vaccine, they found evidence that T-cells were created in response to the vaccine that travelled to the tumor and attacked tumor cells. They also found that patients who received vaccines targeting the greatest number of mutant proteins had the best responses. This finding may help scientists create even more effective personalized cancer vaccines.

Recent studies have demonstrated that personalized cancer treatments may prevent recurrence in patients who had surgery to remove skin or pancreas cancer tumors. The new study adds to our understanding, suggesting that personalized cancer vaccines may also help shrink or eliminate established tumors, and is therefore an approach that could be helpful across many types of cancers beyond liver cancer.

“The role of personalized cancer vaccines is expanding,” Yarchoan says.

Additional study co-authors were Daniel H. Shu, Elana J. Fertig and Luciane T. Kagohara of Johns Hopkins. Other researchers contributing to the work were from the New Zealand Liver Transplant Unit at the University of Auckland in New Zealand; the Tisch Cancer Institute at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York; Personalis Inc. in Fremont, California; Confluence Stat in Cooper City, Florida; University of Central Florida College of Medicine in Orlando; and the Vaccine and Immunotherapy Center at The Wistar Institute and and Geneos Therapeutics in Philadelphia where the vaccine platform was developed.

The trial was sponsored by Geneos Therapeutics.

Yarchoan receives other support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Incyte, Genentech, Exelixis, Eisai, AstraZeneca, Replimune and Hepion. Yarchoan also has equity in Adventris. Fertig is on the scientific advisory board of Viosera Therapeutics/Resistance Bio and is a consultant for Mestag Therapeutics and Merck. Jaffee has received personal fees from Achilles, DragonFly, the Parker Institute CPRIT, Surge, HDTbio, Mestag, Medical Home Group. She has grants from Lustgarten, Genentech, Bristol Meyers Squibb, and Break Through Cancer for other studies and receives other support from Abmeta and Adventris. These relationships are managed by The Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict-of-interest policies.