Researchers track common nighthawks across the Americas to shed light on declining populations

A new study by University of Alberta biologists has created a comprehensive picture of the 10,000-kilometre migratory route of common nighthawks using GPS data. The study is the first step in analyzing where and why the birds’ population numbers are declining.

“Like many migratory bird species, common nighthawks are declining, but the rate of those declines varies across North America,” said Elly Knight, lead author and PhD student in the Department of Biological Sciences. “Figuring out what causes those declines can be difficult and complicated for migratory species like the nighthawk because they occupy so many different places during the year.”

The project brought together researchers from the U of A, Environment and Climate Change Canada and the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center through the Migratory Connectivity Project in a massive collaboration across 13 locations throughout North America.

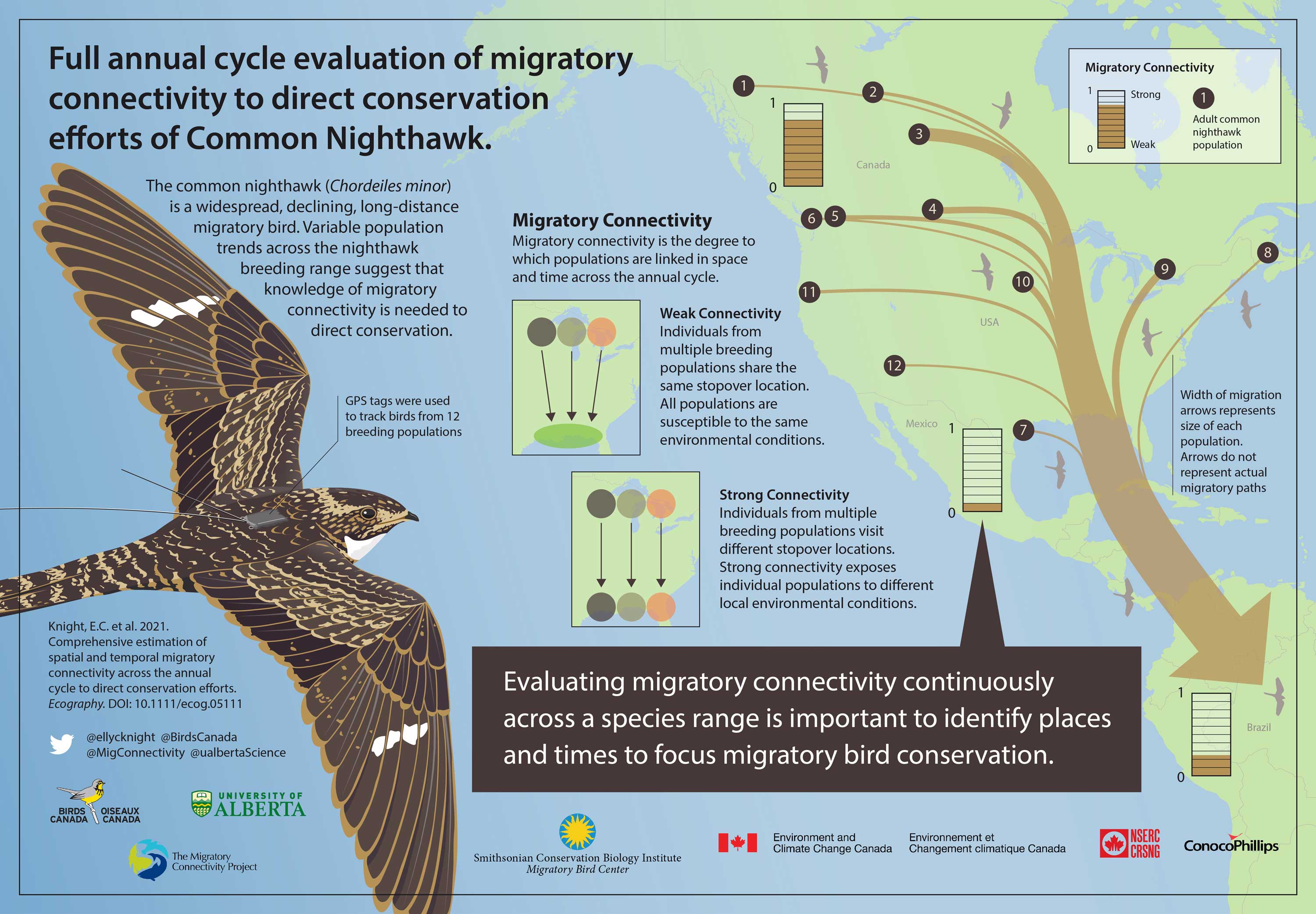

During the summer months, the researchers fitted common nighthawks in North America with small backpacks equipped with GPS transmitters. The researchers took a comprehensive approach to understanding migratory connectivity, which is the degree to which birds from separate populations stick together during their migrations.

“This is a critical start to developing conservation approaches, because it allows us to focus in on the times and places where population declines might occur,” said Knight, who completed the research under the supervision of Professor Erin Bayne. “Without understanding migratory connectivity, there are a myriad of potential reasons why a migratory species might be declining. Without the full picture, we might miss times and places where population declines are occurring.”

Common nighthawks breed in North America but migrate in the fall up to 10,000 kilometres south to the Amazon and Cerrado biomes of South America. The birds make numerous stops along their journey, and GPS tracking allows biologists to understand where and when they’re spending their time outside of their breeding areas.

“We were surprised to find that, despite being distributed across North America, common nighthawks essentially use the same migratory route to their wintering grounds in South America,” said Knight of the findings. “All breeding populations fly east or west to congregate in the midwestern United States along what we call the Mississippi migration flyway. From there, they all mix together and take a common route south across the Gulf of Mexico, down through the northern Andes and on to their wintering grounds, mostly in Brazil. That common route means that there’s little migratory connectivity for common nighthawks outside the breeding season.

“Now that we understand common nighthawk migratory connectivity, we can take the next steps along the path to understanding what limits their populations,” Knight added. “We plan to focus on the times and places with elevated connectivity: breeding, fall migration in North America, and prior to crossing the Gulf of Mexico during spring migration.”

The researchers will compare hypotheses for the potential causes of declines that could occur in those areas and relate them to population trend data to see what explains the differences in trends between populations.

The collaborative project involved 29 researchers from 17 organizations, along with many volunteers. The project was led by researchers from the U of A, Environment and Climate Change Canada and the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center. Major funding was provided by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Environment and Climate Change Canada and ConocoPhillips.

The study, “Comprehensive estimation of spatial and temporal migratory connectivity across the annual cycle to direct conservation efforts,” was published in Ecography.