Skin Patch Trial: Early Warning System for Lung Transplant Rejection

Rejection may show as a rash on the donated skin patch, often before the body has started to reject the lungs. If such a rash is seen, a tiny biopsy from the skin will be taken, as a step to confirm the presence of rejection.

If the trial is a success and the approach can be rolled out to all lung transplant recipients, the research team believe it could cut rejection by up to 50%.

The SENTINEL trial started in April 2024 and will recruit 152 patients over three years. The £2million trial is run by the Surgical Intervention Trials Unit (SITU) at the Nuffield Department of Surgical Sciences, University of Oxford in collaboration with NHS Blood and Transplant and the five UK lung transplant centres and funded by a Medical Research Council (MRC) and National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) partnership.

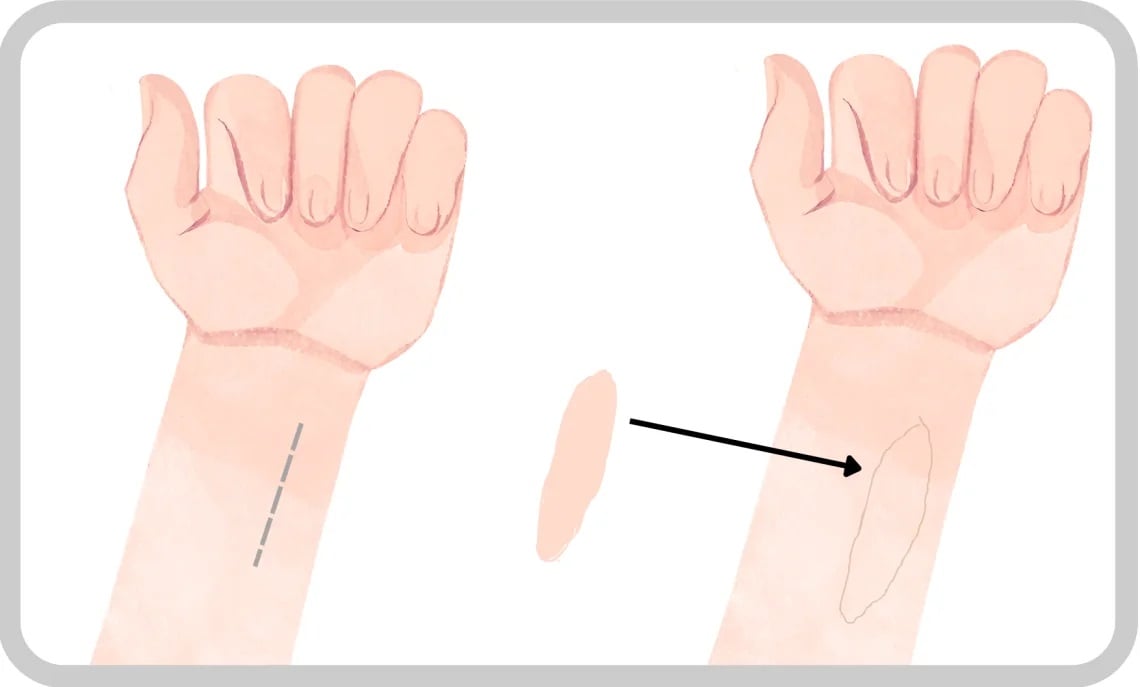

Patients will receive a 10 x 3cm skin patch from the forearm of the organ donor, which will be transplanted onto the under-surface of the patient’s forearm at the same time as the lung transplant. The skin transplant will be carried out by an independent plastic surgeon.

Skin seems to reject earlier than other organs and is easily visible at all times. Doctors can treat the rejection as soon as a rash appears, to try to prevent the lung from also rejecting.

Chief Investigator, Henk Giele, Associate Professor of Plastic, Reconstructive, Transplant and Hand Surgery at Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Surgical Sciences, said: ‘Lungs are prone to rejection due to their exposure to outside air and high propensity to infection. It is often difficult to know if a reaction is caused by infection or rejection as they look the same at the early stages, but the treatments for each are completely opposite. It’s for this reason that we have focused the SENTINEL trial on the lungs – a visible warning system like this is crucial for all transplants, but especially those with higher rejection rates.’

Lung transplant rejection rates are high and cause injury – around 55% of patients are alive after five years. Rejection is monitored through tests of lung function, blood tests, X-rays and lung biopsies but it’s difficult to identify until it is already quite advanced.

Identifying early signs of rejection allows earlier and more personalised treatment, helping the organ to work for longer. If there are no signs of rejection, immunosuppressant medication can possibly be reduced, minimising side effects including higher risks of cancer and diabetes.

The transplants will be carried out by the lung transplants teams at specialist Cardiothoracic Centres across England. Donor families will need to give consent for the skin transplant to take place, which will be requested by NHS Blood and Transplant nurses.

SENTINEL skin grafts have previously been used in studies where patients received intestinal transplants. It was observed that patients who received a skin patch experienced a much lower rate of organ rejection – around half of what would be expected, suggesting that the patch helped to prevent rejection as well as being a useful monitor of early rejection.

Emma Lawson, Organ Donation Innovation and Research Lead at NHS Blood and Transplant, said: ‘NHS Blood and Transplant is honoured to support the SENTINEL trial by matching suitable patients for the retrieval and transplant and via our specialist nurses in organ donation, who will work with the generous donor families to secure the extra consents needed.

‘Transplants and all of the wonderful benefits they bring are only possible thanks to our fantastic donors and we urge people to register their donation choices on the Organ Donor Register.’

Andrew Fisher, Professor of Respiratory Transplant Medicine, at Newcastle University Translational and Clinical Research Unit, said: ‘I am delighted that the SENTINEL skin patch trial has now started to recruit patients waiting for a lung transplant from across the UK. If successful, the trial has the potential to revolutionise the way lung transplants are performed in the future and reduce the fear associated with detecting and treating rejection early.’

Health Minister, Maria Caulfield, said: ‘This trial offers hope to lung transplant patients across the country. Early detection of organ rejection means a healthier transplant, giving people greater control of their care and speeding up access to treatment.

‘We are committed to funding innovative research like this through the National Institute for Health and Care Research, which will help us revolutionise transplants, minimise side effects, and ultimately save lives.’