Study finds mental health problems during COVID highly variable by symptom cluster and population group

People already diagnosed with a mental disorder before the COVID-19 pandemic did not show a disproportionate increase in symptoms afterwards. This is one result from the first systematic review of longitudinal studies following their study population from before to during the first eighteen months of the pandemic.

Even in the first eighteen months after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, an overwhelming number of scientific studies appeared on the impact of ‘COVID’ on mental health. ‘But the vast majority of these had not already been following their research population before the pandemic broke out,’ says Psychologist Eiko Fried from Leiden University, who works on measuring, modeling, and ultimately better understanding mental health problems. ‘So what can we learn from those studies with repeated measurements?’

From 10,000 to 97 studies

With researchers from the University of Pittsburgh, Fried now published the first systematic review of studies published between 29 January, 2020 and 24 June, 2021 that had been following specific groups even before the pandemic, and were therefore able to measure changes in symptoms.

Fried: ‘Also, we tried to understand results at a more fine-grained level. First, we distinguished between clusters of symptoms, such as anxiety disorders, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Second, we investigated to what degree particular populations were affected, such as students, military veterans, or people with pre-existing physical conditions.’

In total, the researchers found almost 10,000 studies on the mental effects of the COVID pandemic published in the first eighteen months of the pandemic. After selecting those that met their inclusion criteria, 97 publications remained, which the team then went through from start to finish.

‘Mental problems are complex and multifactorial’

Instead of simple results, such as that mental health problems generally increased, the results were ‘messy and mixed’, Fried says. And that, at the same time, is one of the most important messages the researchers want to convey to the world: mental problems are, after all, complex and multifactorial. If you really want to uncover information on which to base interventions and policy guidelines, you always have to look with a magnifying glass.

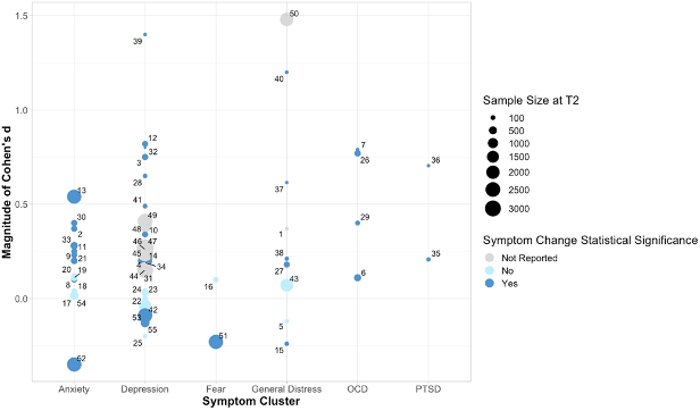

Some general conclusions did stand out, as the graph below shows. For instance, there was a clear increase in symptoms in the domains of ‘anxiety’ and ‘depression’.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

And symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder increased in all studies that had looked into it; The graph shows no ‘dots’ at or below the zero line. ‘Symptom increase was particularly elevated for people with washing-checking related symptoms’, Fried specifies. ‘Which should come as no surprise.’

In contrast, for PTSD, for which only 5 studies could be included in the review, the results were highly varied. ‘But what really surprised us,’ says Fried, ‘was that people who had already been diagnosed with a mental disorder before the pandemic did not show a disproportionate increase in symptoms. Except – again – in the domain of obsessive-compulsive disorders.’

Children and adolescents presented the strongest increases in symptoms across the board, and women between ages 20 and 40 showed a prominent increase in anxiety and depression symptoms. The latter is consistent with studies showing that caregiving work increased for women, in particular in times when schools were closed down.

Decrease in symptoms

What is further striking is that symptoms sometimes even decreased during the COVID period. A study among 2364 Chinese undergraduates, for instance, showed a clear decrease in anxiety and depression.

Fried: ‘I can only speculate as to why, there is much we don’t know. But you can think of some explanations. For example, some students may have experienced lower levels of school stress during lockdowns, and perhaps teachers were more accommodating.’

The researchers conclude that mental health responding during the pandemic varied as a function of both symptom cluster and sample characteristics. Variability in responding should therefore be a key consideration guiding future research and intervention.