Study Reveals Higher Education Enhances Earnings and Mental Well-Being Following Workplace Injuries

Job injuries occur mostly in physically demanding jobs, and they can have significant health and income consequences for the individual. Even ten years after a worker has suffered a serious injury, their average use of painkillers and antidepressants is significantly higher than before the injury, and their average income is about 40 per cent lower.

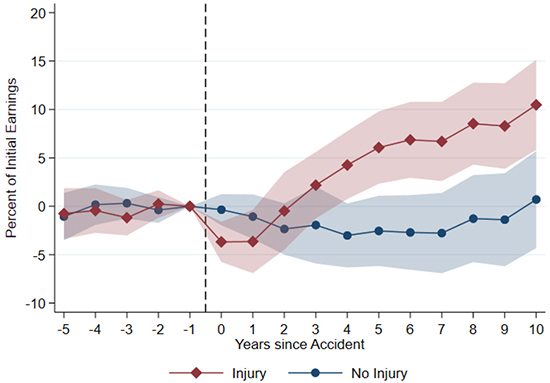

However, it doesn’t have to be this way. In a new analysis, economists conclude that higher education, which gives access to less physically demanding jobs, typically leads to a significantly higher average wage income than before the work injury.

“Our calculations actually show that people with work-related injuries who continue their education overtake their non-injured colleagues in terms of salary just a few years after the accident,” says Jakob Roland Munch, Professor at the Department of Economics at the University of Copenhagen.

Clear societal benefits

Together with Pernille Plato from the University of Copenhagen and Anders Humlum from the University of Chicago, Jakob Roland Munch also find a large gain for society from retraining people with work-related injuries.

“The surplus is about six times greater than the cost of the education. The workers who return to school receive fewer social benefits and their higher income provides the state with more tax revenue,” says Jakob Roland Munch.

According to the economists, there is another reason why higher education benefits both society and the injured worker: Workers who don’t return to school often end up on early retirement, and they are also more likely to be prescribed antidepressants.

A huge potential

However, not all people with workplace injuries continue their education. Two things in particular stand in the way.

“Firstly, you need to be able to start a higher education programme without first having to complete upper secondary education. Secondly, you need to be granted educational rehabilitation,” explains Jakob Roland Munch.

Only 13 per cent of those injured at work continue their education. And even fewer among 40-50-year-olds, with only six per cent returning to school after an occupational injury.

Jakob Roland Munch believes that everything speaks in favour of strengthening education efforts so that more people, especially middle-aged people with work-related injuries, continue their education.

“Everyone wins from this. People with higher education earn considerably more than before their work injury, and their mental health improves. At the same time, people move from early retirement to full-time employment – so there are also substantial gains for society,” he concludes.