Survey reveals COVID-19’s significant stress on Stanford faculty

Members of the Faculty Women’s Forum presented to the Faculty Senate results of a survey that reflect the stress caused by COVID-19, particularly among women faculty, as well as those who are pre-tenure, at the lowest salary levels and with family obligations.

The COVID-19 pandemic and its effects on work-life balance and teaching, research and service have caused significant stress for Stanford faculty members, particularly women faculty, as well as faculty members who are at the lowest level of the Stanford professoriate salary scale, are pre-tenure and who have at-home and family obligations.

Professors Anne Joseph O’Connell, law, and Sara Singer, medicine, delivered to the Faculty Senate a presentation on a quality-of-life survey conducted by the Faculty Women’s Forum. (Image credit: Andrew Brodhead)

A faculty quality-of-life survey conducted by the Faculty Women’s Forum in late 2020 revealed that untenured faculty members are especially concerned about the long-term effects of COVID-19 on tenure progress and about how the pandemic will be addressed in promotion reviews. The survey also reflected the perception among respondents that the university needs to do more to avoid faculty attrition and increasing inequity, according to the members of the Faculty Women’s Forum.

Findings of the survey were presented to the Faculty Senate on Thursday by Anne Joseph O’Connell, the Abelbert H. Sweet Professor in Law, and Sara Singer, professor of medicine. During the meeting, the Faculty Senate also heard a report on academic continuity during the pandemic and learned more about the decision to invite back juniors and seniors for spring quarter.

A lot more stress

O’Connell and Singer reported that the Faculty Women’s Forum survey found that the pandemic caused “a lot more stress” for 57 percent of all respondents, with the number higher for women – 60 percent – than for men – 49 percent. Broken down, 61 percent of pre-tenured faculty, 61 percent of those at the lower end of the salary scale and 62 percent of those caring for children said they were especially under duress.

Thirty-six percent of all respondents said they were dissatisfied with Stanford’s COVID-19 response, with the highest dissatisfaction (46 percent) seen among pre-tenured faculty. Twenty-seven percent of those with incomes between $100,000 and $150,000 indicated they are more likely to leave Stanford post-COVID.

Particularly pronounced in the survey findings is the pandemic’s effect on care for children and other dependents. Forty-five percent of respondents said they were spending at least four more hours per day as a principal caregiver compared with prior to COVID-19. Women bore more of the caregiving responsibilities than their male counterparts. Fifty percent of women and 33 percent of men said they were spending at least four more hours per day as a principal caregiver. Additional caregiver duties were highest among associate professors (52 percent) followed by assistant professors (48 percent). Women faculty also reported bearing a higher burden as educators for their children at home.

Partly as a result, affected faculty say they are spending less time in the pursuit of research. The survey found that 75 percent of respondents anticipated spending less time on research, and 85 percent of those respondents said they expect to decline, cancel or postpone a publishing, proposal or research commitment because of COVID. The survey results indicate that many faculty members are spending more time dealing with the challenges of online teaching, participating in university service activities, and advising and mentoring students who are also struggling with the effects of the pandemic.

The survey was sent to 1,547 faculty members and was open between Oct. 9 and Nov. 6, 2020. The survey was sent to all 710 women faculty, as well as 837 male faculty members – or about half the total – with dependents on their health insurance. Fifty-four percent of the 527 responses came from women faculty. Only 138 male faculty – or 16 percent of men sent the survey – responded. Survey organizers attribute that low number to men likely believing they received it by mistake.

Survey respondents were encouraged to offer personal comments expressing their experiences.

“Some of these quotes are very disturbing about the stress levels faculty were and are continuing to experience,” O’Connell said.

O’Connell and Singer said respondents acknowledged the mitigations already implemented by individual departments and by the university overall. Among those cited included, for example, the tenure clock extension, post-pandemic research quarters for junior faculty, course and service relief, and assistance for online teaching. Faculty respondents, however, cited the need for additional relief, including, for example, additional mental health offerings, help with family COVID testing, an expansion of childcare options and an elimination of the hiring and salary freezes. They also expressed concern that mitigations at the department level often had to be individually negotiated and that the repercussions of COVID-19 are likely to be long-lasting for many careers.

Provost Persis Drell credited the Faculty Women’s Forum survey findings with spurring many of the university’s efforts to help diminish stress on faculty members. (Image credit: Andrew Brodhead)

Provost Persis Drell expressed appreciation for the work of the Faculty Women’s Forum and credited the survey findings with spurring many of the university’s mitigations instituted since the survey was administered. She outlined examples of steps the university has taken to help diminish stress on faculty members. Her list included such measures as teaching and administrative relief during and after the pandemic, increased financial assistance, bridge funding for faculty and their students who have gaps in grant support or other assistance, tenure clock extensions and technology support.

“The pandemic has interrupted careers; it has placed unprecedented stress on faculty and dragged on much longer than any of us had originally anticipated,” Drell said. “We have been looking for ways to support our community. All sectors of our population have struggled.”

Both the provost and President Marc Tessier-Lavigne expressed support for faculty members going forward.

“The pandemic has been difficult for everybody, but it has exacerbated disparities,” Tessier-Lavigne said. “As we emerge from the pandemic it may be normal for some people. For others, they will have been held back. We will make sure we attend to those long-term impacts, not just in the coming weeks and months, but also in the coming years. Some people will be affected in very serious ways for a very long time, and we will not forget that.”

Spring quarter

The Faculty Senate meeting came on the heels of the announcement that the university would invite back to campus juniors and seniors for the spring quarter. Tessier-Lavigne, in his report to the senate, said the decision was guided by the same philosophy that has informed the university’s COVID-19 responses to date.

“Throughout the pandemic, our approach has been simple,” he said. “It has been to do our utmost to support members of our community in resuming activities and pursuing their aspirations, to the extent that it can be done safely and within public health guidelines.”

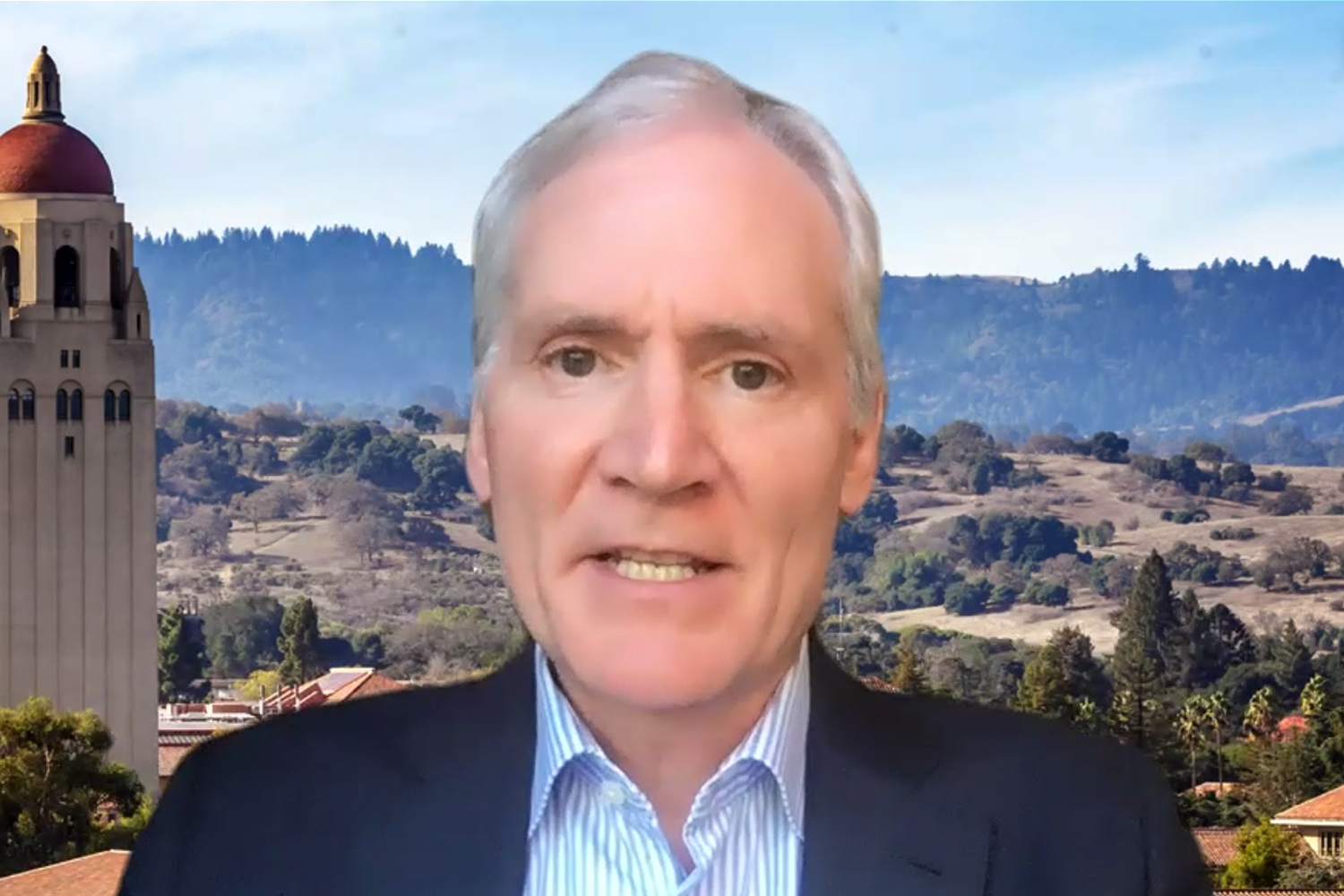

President Marc Tessier-Lavigne spoke to the senate about the university’s decision to invite juniors and seniors back to campus for spring quarter. (Image credit: Andrew Brodhead)

He added, “That’s why, for example, we worked very hard in the spring to enable lab-based and archival-based research to resume as rapidly as possible. It’s also the reason we pushed hard to enable our graduate and professional students to return to campus. This same philosophy has also guided our decision-making about bringing undergraduates back to campus for the spring quarter.”

Tessier-Lavigne noted the accelerating pace of vaccinations and the falling infection rate in the region, saying, “There is light at the end of the tunnel.”

Among the decision criteria used to invite students back were the public health situation in Santa Clara County and any limitations on hospital capacity, the university’s ability to ensure the systems and staffing necessary to bring students back safely and support them on campus, and the nature of the in-person student experience the university could deliver.

But the decision to return or not, he said, is ultimately that of students, especially since most courses will remain virtual. But, he said, “While many restrictions will remain in place, we have greater hope of offering a meaningful on-campus experience in the spring than we did during winter quarter.”

Drell, in her report, reiterated the president’s optimism about the downward trend in positive COVID-19 cases on campus. In the week ending Feb. 19, there were two student positive tests, five employee positive tests and five other positive cases reported among staff and faculty. She compared those numbers with the week of Jan. 4, when there were 97 cases among the Stanford community.

Drell also reported that San Mateo County, where Stanford Redwood City is located, has moved out of the purple tier to the less restrictive red tier in the state’s color-coded risk dashboard. Santa Clara County, where the main campus is located, is expected to follow shortly.

Drell said that vaccination availability and procedures have been a vexing challenge. But supplies are increasing in both counties, and appointments are beginning to be scheduled for people who are in food and agriculture, emergency services and education.

“We are sorting through what we know and what we don’t know,” she said. “We will have a communication tomorrow [Friday] with the details.”

Academic continuity

In a presentation that vacillated between sobering and optimistic, Sarah Church, vice provost for undergraduate education, reviewed the academic pivots the university made in response to the pandemic and outlined the challenges students faced as they sought to continue their studies remotely.

Calling the past year “a wild journey,” Church made the presentation on behalf of the Academic Continuity Team, which she chairs with Mary Beth Mudgett, senior associate dean for undergraduate educational initiatives and professor of biology.

Sarah Church, vice provost for undergraduate education, made a presentation on academic continuity during the pandemic. (Image credit: Andrew Brodhead)

The committee was charged with ensuring the continuity of the Stanford educational mission during the pandemic, while keeping the community as safe as possible. Among the committee’s accomplishments were rebuilding the university’s educational delivery and support system, the registrar systems, academic calendar and classroom meeting patterns.

“We really had to redo and rewrite everything about the way we support educational activities at Stanford,” Church said.

In addition, among its many other activities, the group worked with the Office of Community Standards to interpret the Honor Code for an online experience, reimagined summer session 2020, planned the Frosh Fall Start, provided additional support for faculty and curriculum development and developed two key websites: Teach Anywhere and Teaching Commons. Among its ongoing work are supporting remote teaching needs, planning for in-person courses and collecting data about the online experience.

After reviewing the ways in which academic programs pivoted to meet the challenges of the pandemic, Church outlined how those efforts paid off. For instance, she called autumn 2020 undergraduate enrollment “robust,” reporting that 5,125 students were enrolled full time off campus and 646 on campus, while 737 students opted for a flex term that allowed them to take up to 5 units tuition free. Only 733 students, or 10 percent of the undergraduate body, chose to take a leave.

Church said enrollments during winter quarter have been similar, but with a slightly higher percentage of undergraduates on leave. She anticipates spring quarter enrollments to be robust, but summer quarter enrollments to be low.

Church also presented sobering data from a student survey conducted in spring 2019-20 that showed 83 percent of undergraduates reported difficulty focusing or paying attention to online instruction. Some 66 percent also reported that course lessons and activities didn’t necessarily translate well to an online environment. In addition, 40 percent reported challenges in negotiating time zone differences.

Most students found that their internet access was sufficient to participate fully in online Zoom courses, meetings and other high-bandwidth activities. But Church reported troubling variations in the experiences of first-generation, low-income (FLI) students. While 86 percent of non-FLI students reported that their internet was sufficient most or all the time, the number dropped to 71 percent for FLI students.

Similarly, 40 percent of FLI students reported having a productive, quiet, private or safe place to study. In contrast, 62 percent of non-FLI students reported access to all four.

Mitigation efforts continue, Church said, citing the current on-campus accommodation of some 1,500 undergraduate students with special circumstances, including those with unsuitable living circumstances, international students with visa challenges, students doing honors research and student athletes. Learning Tech and Spaces continues to do equipment loans to students, and the TEACH symposium is offering sessions describing how to navigate different time zones.

Moving forward, Church suggested that the university’s Honor Code needs to be reconsidered. Calling it “already frayed around the edges,” she said the pandemic experience reflected the fact that the Honor Code was not written for an online environment.

That was among the many lessons learned by the Academic Continuity Team members. Others included how much preparation remote classes require of instructors and the challenges created by decentralization in such areas as classroom control and communication. But she singled out faculty members for praise for their embracing online education and their efforts in doing everything from rebuilding lesson plans to sending out specialized kits to students at home.

Church said the experience of the past several months has resulted in increased collaboration among key campus groups. Still, she said, the Academic Continuity Team believes there remains widespread confusion about where responsibility lies for academic decisions.

Graduate support

The Faculty Senate also heard from Stacey Bent, vice provost for graduate education and postdoctoral affairs, who outlined steps the university is taking to help doctoral students whose research has been disrupted due to COVID-19. The provost, she said, has committed additional central funds for 2021-22 that will complement funds schools and departments are also using to support students.

Bent said the specific strategies being implemented include increasing the number of late-stage fellowships, creating additional teaching assistantships to meet increased teaching needs similar to the summer 2020 Provost’s Teaching Fellowships, developing a model of need-based dissertation fellowships that allow students to focus on research and writing, and considering postdoctoral opportunities to help address disruption to the job market for PhD graduates.

Bent also reaffirmed the commitment to support for 12 months for up to five years for doctoral students at earlier stages and for new students.

“The aim is to ensure that all doctoral students who have experienced significant COVID-related delays will be supported,” she said.

ASSU resolution

In other action, the Faculty Senate Steering Committee shared a resolution from the Associated Students of Stanford University (ASSU) that advocates permanently unhousing fraternities and sororities on campus. Stanford currently has 10 Interfraternity Council (IFC) and seven Intersorority Council (ISC) organizations.

The Faculty Senate took no action on the resolution because it has no jurisdiction over residential housing. However, it heard a report from Vice Provost for Student Affairs Susie Brubaker-Cole, who outlined residential governance, jurisdiction and decision making.

In the resolution, sponsors Kari Barclay, Graduate Student Council co-chair; Danny Nguyen, Undergraduate Senate deputy chair; and Vianna Vo, ASSU president, assert that the IFC and ISC organization members of are “predominantly wealthy, white, able-bodied and otherwise privileged individuals who have greater access to Row housing due to their membership in these organizations.”

In their resolution, they draw a distinction between the IFC and ISC organizations and the Multicultural Greek Council and African American Fraternal and Sororal Association organizations, which provide more inclusive spaces for marginalized communities.