The Sachs Program announces winners of AAPI grants

The Sachs Program for Arts Innovation announced 14 projects awarded funds in support of Asian American and Pacific Islander artists.

The projects include students, faculty, staff, and alumni. Six grantees are students, three are staff, two are alumni, one is faculty, and two others are recent alumni. Disciplines funded range from opera to children’s literature, film to mural arts.

“We felt that there were all of these issues locally and nationally around violence against Asian-American and Pacific Islanders, and we wanted to create this opportunity to support AAPI artists and practitioners in our community, to acknowledge their critical [contributions] to our creative community, and give them support to do work whether or not it was directly engaging these issues,” says Chloe Reison, associate director of The Sachs Program. “One thing we didn’t want to stipulate with these grant opportunities was that the practitioners had to produce something that was in response to what was happening nationally, or that they even produce work that was about identity, though many did.”

These grants are in addition to the call for proposals issued in summer 2020 for projects led by or primarily serving Black artists at Penn, funding eight projects. Both are in addition to the full grant cycle announced in May that funded 25 new arts projects and totaled $177,000 in funding.

These responsive grants have been new for The Sachs Program, intended to provide resources where needed, when needed, especially in the context of ongoing conversations around social justice, systemic inequality, and targeted violence. They’re also the first grants to be open to alumni applicants.

“We wanted to try and be responsive in the moment while we struggle with the issues we know we have to work on. And I think we received a strong response to these opportunities,” says John McInerney, executive director of The Sachs Program. “That was very great to see and one of the notable things is we heard form a lot of people in communities we had not heard from before. That was very helpful for us to recognize that we have to continue to encourage people to apply for all opportunities we have.”

Jo Tiongson-Perez is the director of marketing and communications at the Penn Museum and one recipient of the grants. She, in collaboration with college friend Denise Orosa, who like Tiongson-Perez is from Manila, will work on a children’s book containing eight lyrical retellings of indigenous Philippine stories. The book’s eight stories represent the eight provinces that rebelled against three centuries of Spanish colonial rule. It will be told in both English and Tagalog, a language spoken in the Philippines.

The project, she says, was inspired by conversations with her 13-year-old daughter, who has asked about her Filipino roots. The answers she was able to provide, she felt, were unsatisfying.

“I realized all the stories I was telling her were very Western,” Tiongson-Perez says. “I know a lot of Hans Christian Anderson, the Brothers Grimm, and I know maybe one or two native Filipino stories.”

The realization prompted her to plan a project to address this, bringing Filipino stories to people like her daughter, who has only been to the Philippines once, and Orosa’s son, who has never been to the Philippines. Tiongson-Perez is currently in the research phase of the project but aims to cover tales that date before Spanish colonization of the Philippines.

“It’s going to be a discovery for me, too,” she says. “There wasn’t much of a focus in my own education in the Philippines [on Filipino stories]. Education is predominantly taught in English, and when we learn about Filipino history, the books we have are Western, in terms of children’s stories. So, this is an exploration and fact finding.”

The plan is to hire artists from the Philippines to illustrate the stories. She and Orosa anticipate these drawings will contain native images, symbols, flowers, and more, and will be educational for both parents and children. The book will contain a glossary with short, digestible facts to note the significance of certain references. She hopes to begin work on the book this summer and have it ready for production by November 2022.

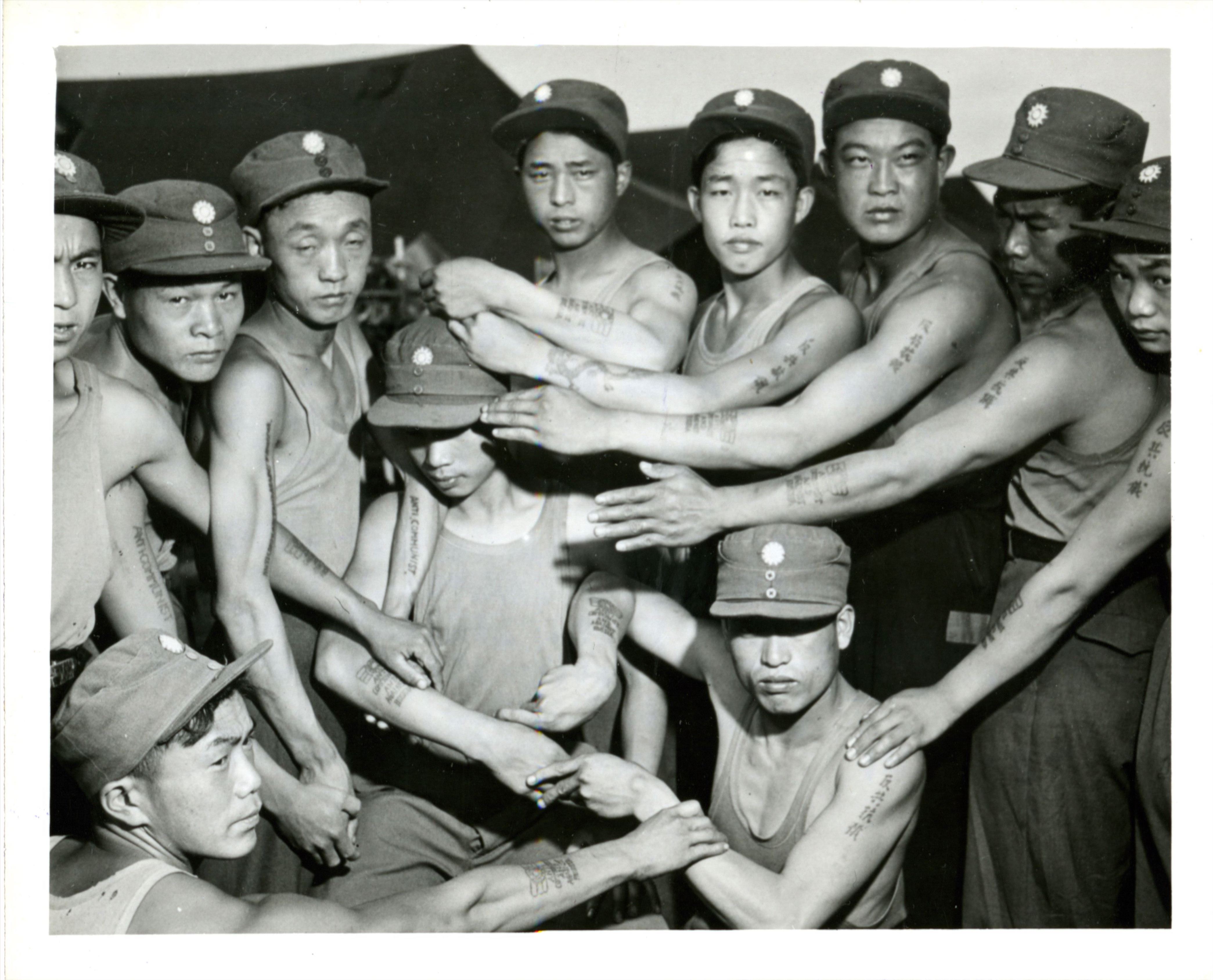

Kyuri Jeon, meanwhile, is a 2020 MFA alumna who received a grant for her short film project, “Thread & Needle,” which explores the use of tattoos in Korea.

“’Thread & Needle’ is a short film that unpacks the questions of how structural violence and oppression linger on our bodies, and my body, and our possession of self and how they have shaped my own experience living in the contemporary society,” Jeon explains.

Her curiosity about tattoos in Korean society stems from a tattoo she received in summer 2019 in South Korea, realizing that tattoos—which are illegal to perform there without a medical license—are social responses. She has since begun a deep dive into the history of tattoos in Korea—through archives there and in the U.S.—and points to examples of how tattoos have been punitive in some cases. For example, during the Korean War, when North Korean and Chinese prisoners of war, held captive by the United Nations, were asked to have anticommunist slogans tattooed on their bodies. It’s notable, she adds, that tattoos and markings are especially taboo in Confucian cultures.

But there are other elements to how tattooing has been entangled in Korean culture, she says, such as their role as a form of remembrance before the Korean War. Those were often DIY tattoos. And, in the 1980s, U.S. Army camps introduced contemporary tattoos to Korea, which have become popular while, somewhat counterintuitively, also retaining a taboo status. Some tattoos of dragons or tigers, for example, can be perceived as association with gangsterism.

Her film project, she says, is “rooted in the continuing legacies of U.S. imperialism,” but also explores the objectification of women (Korean sex workers, Yanggongju, sometimes had heart and arrow tattoos as a demonstration of love to U.S. soldiers, she says), enforced national identity, and a push for Western capitalism.

“It’s in progress with this belief that we all need to bear witness to very ever-present trauma and have the agency to recover and find a sense of belonging,” Jeon says. “On my end, my perspective as an artist, I wanted to find out where my body is coming from.”

She plans to film in the U.S. and Korea by the end of the year to be able to apply for film festivals. Ideally, the film will be complemented with an exhibition.

Other projects include a pop-up exhibit from Department of Music doctoral student Shelley Zhang, highlighting the impact of classical Chinese conductor Li Delun, who played a role as a bridge between a reemerging China and Western orchestras in the 1960s, defying a ban on public performance of Western music. Rupa Pillai, a senior lecturer of Asian American Studies, will create a course for the fall semester that studies altars at nail salons, grocery stores, restaurants, and other Asian-American retailers. And the Penn Vietnamese Student Association will produce its first animated culture show called “Caged Swans,” demonstrating Vietnam’s complex history.

More information about the grants is available at SachsArts.org.