The Sydney Harbour Bridge turns 90

Born on Boxing Day 1867, Sir John Bradfield is arguably one of the University of Sydney’s most famous alumni, having overseen the design and construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge while working at the NSW Department of Public Works.

An early graduate of the University of Sydney, Bradfield studied both a Bachelor and Master of Engineering, receiving the University medal for his work. In 1924 he received the University’s first doctorate of science in engineering, for a thesis entitled ‘The city and suburban electric railways and the Sydney Harbour Bridge’.

Bradfield was later a Fellow of Senate of the University from 1913 to 1943, becoming Deputy Chancellor in 1942. He maintained close links with the University throughout his career, as a trustee of Wesley College in 1917-43, a councillor of the Women’s College from 1931, and a member of the University Club.

University of Sydney academics from a variety of disciplines comment on Bradfield’s legacy and the impact of the Sydney Harbour Bridge 90 years on from its completion.

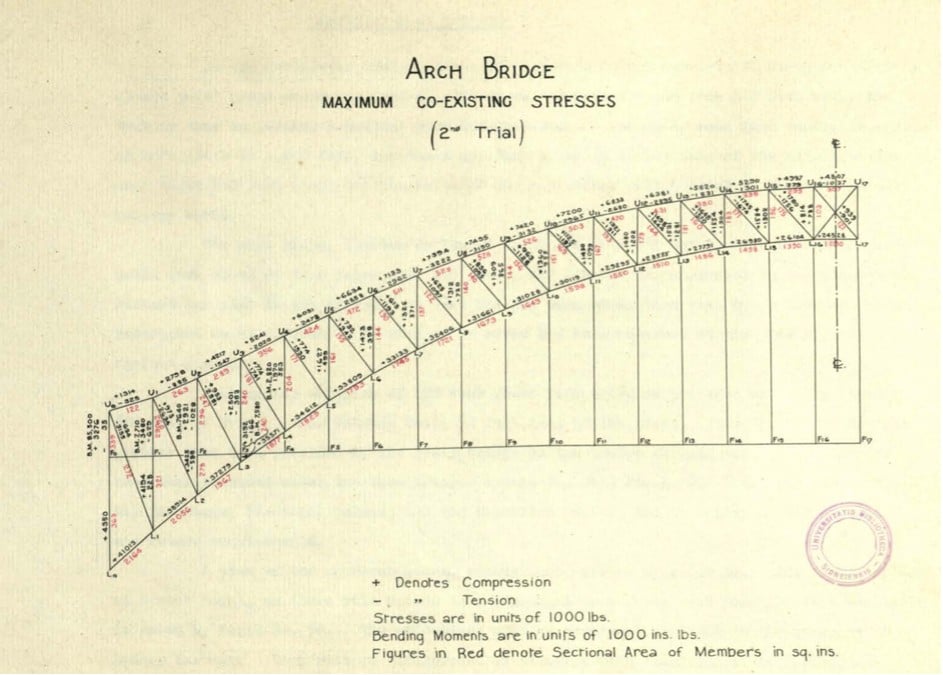

A feat of civil engineering

Professor of Practice Wije ‘Ari’ Ariyaratne is an engineer and bridge expert in the School of Civil Engineering. He was previously the Director of Bridges & Structures at the NSW Roads and Maritime Services, a role for which he received the NSW State Premier’s Award for “Delivering Infrastructure”.

“The Sydney Harbour Bridge was the beginning of today’s Sydney,” said Professor Ariyaratne, who in his previous role was responsible for managing the technical risk of over 59,50 bridges in NSW, including the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

“Everybody has ownership of it: it is us. Sydney wouldn’t be a global city without it. John Bradfield, the Bridge’s lead engineer and a University of Sydney alumnus, was a visionary and a futurist.

“He didn’t design for his day – he designed for the future and for all of us. No one has had a greater impact on this city.”

University is home to the Bradfield Collection

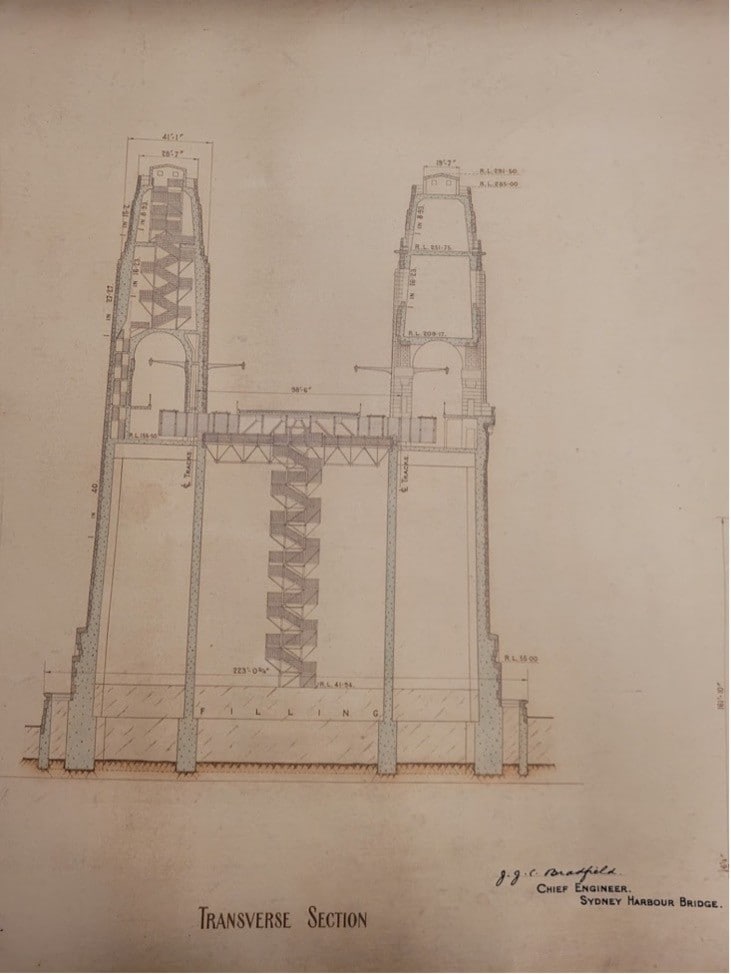

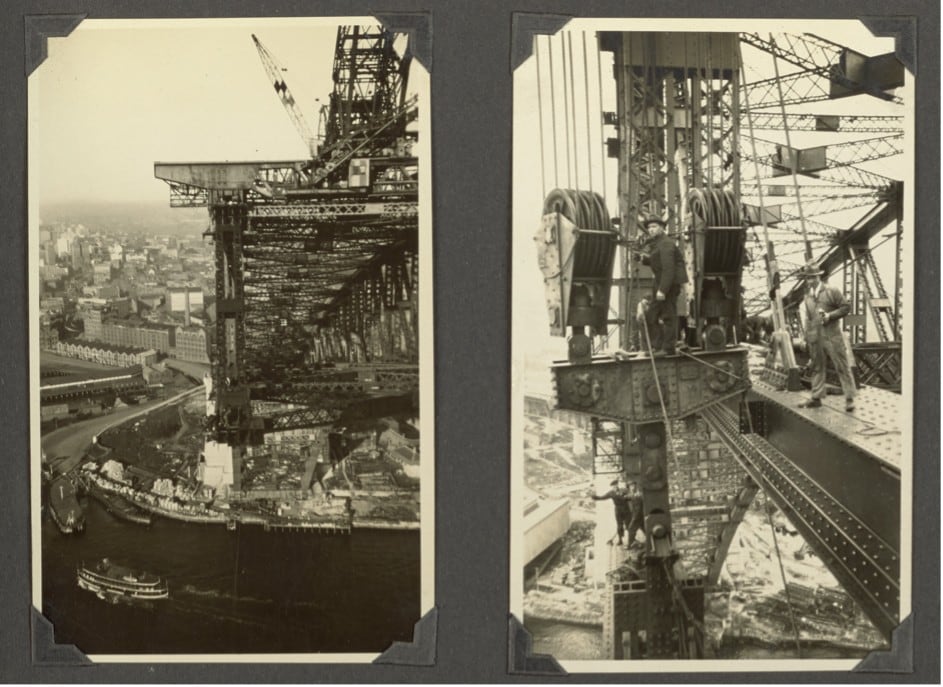

The University of Sydney Library, where Julie Sommerfeldt is the manager of Rare Books and Special Collections, is home to a large Bradfield archive containing detailed drawings and photographs of the Sydney Harbour Bridge’s construction.

“There are hundreds of items in our Bradfield collection, offering rich insights into the design and construction of a Sydney icon. Among the collection’s many intriguing items are a series of alternative designs from other tenders for the bridge. They give a glimpse into what might have been,” said Ms Sommerfeldt.

“Bradfield’s photo albums, complete with his handwritten captions, not only show how the Bridge came to be, but also offer a picture of Sydney as it once was.

“There are extraordinary images of workers standing on the incomplete structure, high above the harbour, with no safety harnesses. Photos from project milestones, such as the setting of the foundation stone, show a sea of men in suits and hats.”

Connecting a separated Sydney

While now a permanent fixture of the harbour city, transport engineer Professor David Levinson from the School of Civil Engineering says the Bridge has played a far more momentous role than what was initially conceived.

“The Harbour Bridge has been far more valuable than imagined, connecting north and south by road, rail, tram, bus, walk, and bike,” said Professor Levinson.

“That it took until 1932 to open, rather than over a century earlier when it was first conceived, indicates many people tried to judge the demand for the bridge by counting the number of people swimming across the harbour, or even taking the ferry, instead of considering the new access it would provide.

“Infrastructure shapes cities in profound ways, and it will be interesting to see how the Harbour Bridge evolves over the next 90 years.”

Infrastructure shapes cities in profound ways, and it will be interesting to see how the Harbour Bridge evolves over the next 90 years.

When the Bridge first opened in 1932, it was tolled in both directions, according to founding director of the Institute of Transport and Logistics Studies (ITLS) in the University of Sydney Business School, Professor David Hensher.

“Opened on 19 March 1932, the 1.15 km Harbour Bridge, operated by Transport for NSW, has been the greatest land use initiative to open accessibility between the northern and southern sides of Sydney, replacing ferries,” said Professor Hensher.

It was not until 1970 that the toll was removed for Northbound commuters, costing $0.20 for the one way journey.

“The toll price rose from $0.20 to $1 in June 1987. In March 1989, the toll for using the bridge increased from $1 to $1.50,” said Professor Hensher.

“It was increased to $2.20 in July 2000, followed by another 80 cents’ increase to $3 in January 2002. The Harbour Bridge changed to cashless tolling on 11 January 2009.

“Since 27 January 2009, a new charging system, namely Time of Day Tolling, has been implemented. Instead of a flat rate, different prices are applied according to the trip time.

“During weekdays, the charge is $4 for peak hours (i.e. 6.30 am to 9.30 am and 4.00 pm to 7.00 pm), $3 for 9.30 am to 4.00 pm or $2.50 from 7.00 pm to 6.30 am. On weekends and public holidays, the toll is $3 from 8.00 am to 8.00 pm or $2.50 from 8.00 pm to 8.00 am.”

The Sydney Harbour Bridge represented a vision of hope

Dr Sophie Loy-Wilson is an expert in Australian history in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences says it is remarkable that the Sydney Harbour Bridge was built during such a bleak period in Australian history.

“Sydney in 1932 was a city marked by extreme poverty. This was the Depression-era. Australia’s unemployment rate had reached 32 percent in 1931, second only to Germany in severity,” said Dr Loy-Wilson.

“Even in such uncertain times, the state government had a big bold plan: the Sydney Harbour Bridge. The Bridge would impact the city in contradictory ways. Families were displaced from north Sydney, but the unemployed found much needed work.

“The Bridge was expensive, but it represented hope and a better life for Sydney people. Sandstone excavations caused dust and debris but also uncovered fossils and other treasures.

“The story of the Habour Bridge is a story of a city on its knees, looking up towards the largest structure the city had ever seen, being pieced together across Sydney Harbour.”

Bridge stands in for the city itself

According to Associate Professor Cameron Logan, an urban and architectural historian in the School of Architecture, Design and Planning, the Sydney Harbour Bridge is representative of the city itself – a global symbol that identifies Sydney and its harbour.

“The Sydney Harbour Bridge stands in for the city itself. It is a powerful connector and symbol; a work of great technical accomplishment but also one of collective endeavour,” said Associate Professor Logan.

It has also acted as a bold, nation-building stamp, facilitating the rapid expansion onto land and forest north of the harbour.

“As we celebrate its anniversary and its symbolic salience, however, we also need to recognise that – as much as anything – it has been a great machine for making real estate. Like other infrastructural works created by the settler society, therefore, it is a mechanism for dominating the landscape and for appropriating land.”