UC Berkeley’s LeConte and Barrows halls lose their names

The names of the University of California, Berkeley’s LeConte Hall and Barrows Hall will be removed, campus officials announced today. The decision, capping a formal review process, was made in response to growing awareness of the controversial legacies of the halls’ namesakes — all of them early, prominent members of the UC faculty — that clash with UC Berkeley’s mission and values.

Brothers John and Joseph LeConte came to Berkeley in 1869 from a Southern slave-holding family, fleeing post-civil war Reconstruction; Joseph LeConte, who, like his brother, served in the Confederacy, used scientific language to promote racist ideas. David Prescott Barrows, UC president from 1919 to 1923, was a colonizer of the Philippines’ education system in the early 1900s and wrote, reflecting the U.S. “humanitarian imperialism” of his time, that “the white, or European, race is, above all others, the great historical race.”

Chancellor Carol Christ, in letters sent to UC President Michael V. Drake, whose consent, along with hers, was required — and given — to undo each honorific naming, said removing the names and acknowledging the university’s past ties to these individuals and their beliefs “will be historically and socially valuable to our campus, … and we hope to strengthen inclusion and belonging” at UC Berkeley.

The decisions reflect a new urgency being felt by U.S. civic and higher education leaders to remove building names and monuments that memorialize individuals who expressed racist and dehumanizing views. They resulted from an assessment of two unnaming proposals — one for LeConte Hall, the other for Barrows Hall — submitted in July by members of the campus community to the chancellor’s Building Name Review Committee. This fall, the 12-member committee of students, staff and faculty unanimously approved dropping the names and sent its recommendations to Christ.

Of the 634 responses solicited by the committee about the proposal for LeConte Hall, home of the physics department, 87% favored unnaming the building. For Barrows Hall, 518 responses were collected; 95% approved of unnaming it. That facility houses a mix of departments, including ethnic studies, political science, sociology, Near Eastern studies and the Energy and Resources Group.

“Our buildings should not be another reminder that we are and have long been despised,” said fourth-year Ph.D. student Caleb E. Dawson, co-president of the Black Graduate Student Association. “They should signal otherwise, and those signals should correspond with institutional norms, policies and practices that make us feel otherwise in our everyday lives.”

Until the two buildings receive new names, either honorific or philanthropic, they will be known, by default, as Physics South (Old LeConte Hall) and Physics North (New LeConte Hall) — the facility has two buildings — and The Social Sciences Building (Barrows Hall). A process for renaming these buildings is being developed, officials said.

The structures will lose the names of men once honored by the campus, but the proposal authors and the Building Name Review Committee also recommended that UC Berkeley makes sure the namesakes’ histories, including what led to the names’ removal, won’t be forgotten, and that it continues to work toward a campus climate that respects and affirms the dignity of all.

“Unnamings are just the tip of the issue. They’re a step in the right direction — a necessary step, but a small step,” said Melissa Charles, UC Berkeley’s assistant director of African American student development. Charles co-authored the proposal to unname Barrows Hall with her colleague, Takiyah Jackson.

Integrative biology professor Paul Fine, chair of the Building Name Review Committee, said today’s announcement “is not about demonizing David Barrows or the LeContes, but about removing offensive symbols we have on campus, so that the people who are here now, and in the future, know that this is their university.”

He added that to be “a truly welcoming institution requires a real investment in making substantive changes to systemic racism, to institutional racism.”

Last January, Boalt Hall at the UC Berkeley School of Law was denamed because of the racist writings of its namesake, John Henry Boalt, a 19th century Oakland attorney. The building currently is called The Law Building.

Christ said the campus unnamings are “but one step among many that we are taking. … I have committed my administration to doing everything in its power to identify and eliminate racism, wherever it may be found on our campus and in our community.”

John and Joseph LeConte

The LeConte name began to disappear in California several years ago. In 2015, for example, the Sierra Club successfully petitioned for Yosemite National Park’s LeConte Memorial Lodge, which honored Joseph LeConte, to be renamed. And the city of Berkeley’s school board voted unanimously in 2017 rename LeConte Elementary School.

The Department of Physics faculty voted overwhelmingly in June to remove the name of LeConte Hall and sent its proposal to the Building Name Review Committee in early July.

The “deciding factor” for the faculty, according to the physics department’s bid to the committee, “was the gross misuse of science by Joseph LeConte to repress and advocate against the rights of African Americans.” The letter said the faculty also had acted in support of calls for action from UC Berkeley student organizations and was catalyzed by the Black Lives Matter movement.

“Both men (John and Joseph LeConte) made important academic contributions, but this does not undo or offset the harm done by their racism,” said UC Berkeley physics professor Frances Hellman, dean of the Division of Mathematical and Physical Sciences.

The LeConte brothers inherited their family’s Georgia plantation, which had an estimated 200 enslaved people, when their father, Louis, died in 1838.

John LeConte was a medical doctor, then a professor of physics and chemistry. He also was a supporter and officer in the Confederacy during the civil war and supervised the military’s Nitre and Mining Bureau operations in upper South Carolina.

LeConte Hall, a two-building facility that has been unnamed, is home to the Department of Physics. Until new names are approved, Old LeConte Hall will be called Physics South and New LeConte Hall will be Physics North. (Xiaoye Yan and The Daily Californian)

His younger brother, Joseph, was a professor of natural science and of natural history and geology; the two brothers taught at South Carolina College. During the war, Joseph LeConte joined the Confederate army, working as a scientist on the manufacture of gunpowder.

Previously, Joseph LeConte had attended Harvard University and studied under biologist and geologist Louis Agassiz, a proponent of polygenism — the view that human races are of different origins and that was used, historically, to advance racial inequality. Although LeConte rejected polygenism, he shared many of Agassiz’s racist beliefs.

The LeContes despaired when, after the war, South Carolina College reopened as the University of South Carolina and welcomed Black students and professors for the first time; by 1876, the school had a predominantly Black student body. Joseph LeConte wrote despondently that it had become “a school for illiterate negroes.”

The siblings left for jobs at the new University of California, where John LeConte became its first faculty member and the initial acting president from 1869 to 1870. He again served as acting president in 1875, then as president for five years.

Joseph LeConte was a noted naturalist and geologist at the university and president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1892 and of the Sierra Club, which he established with John Muir, from 1892 to 1898.

It was also on the Berkeley campus, where Joseph LeConte was considered its most distinguished scientist and scholar, that he wrote works aimed at justifying, through pseudo-scientific language, the inferiority of African Americans and called for their disenfranchisement.

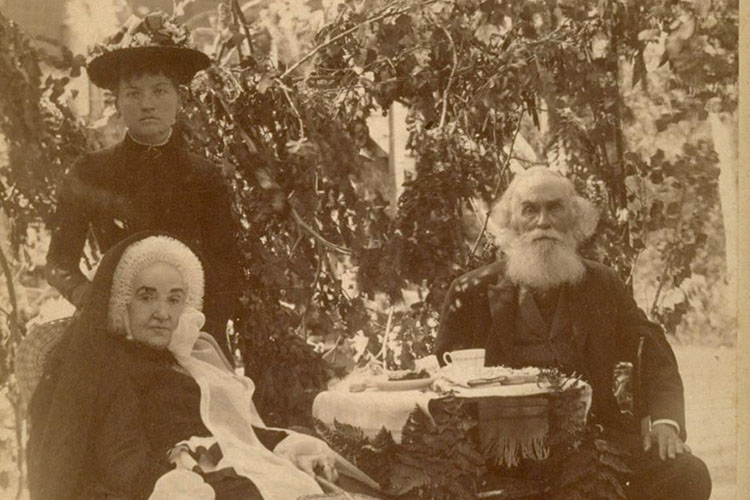

Physicist John LeConte (right) and his wife Eleanor (seated) pose for this photo, taken around 1891, shortly before their deaths. A caregiver stands nearby. John LeConte was UC president from 1869-1870 and from 1875-1881. Both LeConte and his brother, Joseph, were the namesakes for LeConte Hall. (Bancroft Library photo)

In his 1889 article, “The South Revisited,” and in his 1892 book, The Race Problem in the South, he wrote extensively on the “dread race problem” in society and about the superiority of white people over Black people.

In “The South Revisited,” he penned that “race repulsion and race antagonism is … an instinct necessary for the preservation of the purity of the blood of the higher race,” and that when Black people are “largely in excess, so that the control of the superior race is lost, … they are rapidly relapsing into barbarism.”

LeConte also argued that sexual reproduction in plants and animals explains the perils of racial intermixing: “I regard the light-haired blue-eyed Teutonic and the negro as the extreme types, and their mixture as producing the worst effect. … It seems probable then that the mixture of extreme races produces an inferior result.”

His writings, used to justify laws that diminished the rights of African Americans, are in “direct conflict with our university’s campus values and our commitment to diversity and excellence,” Christ wrote to Drake.

Neither brother renounced white supremacy after arriving in California, said Hellman, adding that their story disgraces science. Scientists should “describe the natural world accurately, by following the scientific method rigorously,” she said, “ … and not becoming enmeshed in, influenced by or used to advocate for beliefs or ideologies.

“This illustrates one of the many ways in which diversity of the scientific community is essential to good science and how much the quality of science is diminished without it.”

Metal letters spelling Barrows Hall, removed on Wednesday when the building was unnamed by campus officials, sit in a plastic bucket. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

David Prescott Barrows

Already in 2015, UC Berkeley’s Black Student Union petitioned for David Prescott Barrows’ name to be removed from Barrows Hall. Its work helped pave the way for the unnaming proposal submitted last summer, as did a 2019 request from Filipinx students on campus and editorials by student writers at the Daily Californian.

Barrows, in addition to serving as UC president, was a faculty member on the Berkeley campus from 1910 to 1942. But “Barrows’ words and actions were anti-Black, anti-Filipinx, anti-Indigenous, xenophobic and Anglocentric” and “advanced the interests of white supremacy,” the Barrows unnaming proposal states.

“The idea of having the names (on campus buildings) of men who knowingly and willingly contributed to slavery, Native displacement and theft, colonization and xenomisia angers me,” said Charles. “It’s even more of a slap in the face when the buildings they’re named after — in this case, Barrows Hall — house departments like ethnic studies, African American studies, womxn and gender studies.”

Barrows, who received an M.A. in political science from the UC in 1895 and a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Chicago in 1897, was appointed superintendent of schools in Manila in 1900, after the U.S. occupied the Philippines. From 1903 to 1909, he imposed a new educational system on the people of the Philippines as general superintendent of education.

In UC Berkeley’s Greek Theatre, a row of thrones, or seats, of honor were made in the Greek tradition and typically were dedicated to faculty and administrative staff. Joseph LeConte’s name is on two of the 31 seats that remain — there were 32 — and David Prescott Barrows’ name is on another. (Cal Performances photo by Rob Bean)

In its letter to Christ recommending the unnaming of Barrows Hall, the Building Name Review Committee quoted Barrows’ claim that Filipinos had “an intrinsic inability for self-governance” and were an “illiterate and ignorant class’ to be brought into modernity through the benevolence of American rule.”

His role as a colonizer, said Joi Barrios-LeBlanc, a lecturer in the Department of South and Southeast Asian Studies, “was responsible for the colonial education that privileged English over the Native languages, shaped minds to believe in the superiority of Western culture and reinforced feudal, colonial and pro-imperialist ways of thinking.”

In 1905, Barrows created a textbook for high school students, A History of the Philippines, and it was used in schools in the Philippines until 1924. In it, he “framed a disturbing view of history and race, where people of color are most often considered in relation to whites,” the unnaming proposal states, “and where races can seemingly be ordered in a hierarchy of linear-temporal advancement, relative intelligence, physical attractiveness, and as members of either civil or savage societies.”

He returned to the UC in 1910, this time as a professor of education at Berkeley, and later that year became dean of the graduate school. In 1911, he joined the political science department as a professor and became dean of the faculties in 1913.

Lettering comes down from several exterior locations on the building formerly known as Barrows Hall. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

During World War I, Barrows left campus to become an intelligence officer in the Philippines and also in Siberia. In 1919, he was named UC president, a position he kept until 1923, when he went on sabbatical, visiting Timbuktu and crossing the Sudan. He returned to Berkeley in 1924, became chair of the political science department and taught until his retirement in 1943, while also continuing his military service, retiring as a major general in 1937.

In his writings, Barrows’ characterization of Black people, the unnaming proposal said, was a “thorough dehumanization,” and he wrote that they “are politically incapable, can’t successfully enact self-determination, are vicious, lack free will and can’t recognize their own rights.”

Barrows, in his book, Berbers and Blacks: Impressions of Morocco, Timbuktu, and The Western Sudan, also analyzed British colonization in Africa, saying that, “The tropical coast comprised in British Nigeria probably had as wicked a history as any part of the African shore, before the British took responsibility for it, and gave it a just and humane government.”

UC Berkeley’s Native American Advisory Committee — some of its campus members are from tribes in California and Nevada — also wrote in support of the unnaming. It underscored that Barrows’ adherence to a colonial ideology of “civilizational uplift” was the foundation for “multiple violent policies and atrocities against Native Americans and Indigenous peoples around the globe.”

Blake Simons (right), assistant director of the Fannie Lou Hamer Black Resource Center; third-year student Kyra Abrams (middle), chair of the Black Student Union; and Melissa Charles, assistant director of African American student development, stand outside Barrows Hall, which campus officials unnamed on Nov. 18. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

Removing symbols, pondering next steps

Fine stressed that the unnaming of LeConte and Barrows halls is “important, symbolically, because it sends a clear message that the campus is making changes to be more welcoming.”

The legacy of a building’s namesake, he added, should align with the university’s mission and values, which are part of the Building Name Review Committee Principles. These principles include viewing as UC Berkeley’s “intellectual and ethical responsibility the promotion of an inclusive, global perspective on the peoples and cultures of the world, particularly in light of scholarly traditions that may omit, ignore or silence the perspectives of many groups …” and, whether a building’s name is removed or not, retaining a public record, “perhaps in the form of a plaque,” that notes the history of the building’s naming and the reasons for removing its name.

While some argue that unnaming a building is removing its footprint, Raka Ray, dean of UC Berkeley’s Division of Social Sciences and a professor of sociology and South Asian studies, disagreed. Many departments in her division are housed in what is no longer Barrows Hall.

“Unnaming is not an erasure of history, but a profound acknowledgment of history,” she said, “a reckoning of the present with the past. The unnaming of Barrows represents this acknowledgement and pledges commitment to a future that Berkeley stands for.”

Ray taught in the building for 25 years, she said, “and while I always thought it was ironic that we teach what we teach in a building with Barrows’ name, I never heard a concrete discussion of it. The students I speak with are very pleased about it now, though.”

At the hall formerly known as LeConte, Hellman said the physics department is considering an explanatory page on the department’s website and the installation of a plaque that explains how the building got, and lost, its name.

“A plaque about the LeContes can be used as a place to remember that the world can and should be changed for the better,” she said.

As a new chapter begins for the former Barrows Hall, Barrios-LeBlanc suggested that the campus community “constantly interrogate the intentions of our work as scholars and teachers” and consider how to support the Filipinx community in its long struggle for visibility, equity and justice.

Her students, in learning of David Prescott Barrows’ legacy, she said, experienced surprise, anger and then “a deep desire to forward the struggle for justice.”