University of Bristol research finds insight into miscarriages in tsetse flies

Tsetse are biting flies that transmit the parasites causing sleeping sickness in humans and Nagana in animals. Female tsetse flies, which give birth to enormous, adult-sized live young, can experience miscarriages and these are more likely as they get older.

A new study, published in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution carried out by researchers from the Universities of Bristol, Oxford, Notre Dame in the US, and the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, investigated the causes and consequences of these miscarriages (or spontaneous abortions) in tsetse flies. They asked how abortions affected the size and sex of the next offspring produced, and how factors such as the mother’s nutrition affect the frequency of miscarriages.

The scientists found that early-stage abortions are initially prevalent in very young female tsetse flies and then gradually increase as tsetse females reach older ages. They did not find evidence that abortions are adaptive strategies, in other words, tsetse flies that had abortions did not go on to have larger offspring or more females.

Findings from the study could feed into predictive modelling of tsetse population dynamics, which could ultimately help predict the spread of tsetse-borne diseases.

Dr Sinead English from the University of Bristol’s School of Biological Studies said: “There is a lot of interest in how miscarriage risk depends on a mother’s age and pregnancy stage, but this is difficult to study in part because we lack detailed data on miscarriages across animals (including humans). Using the tsetse fly as a model we can get new insights into this pregnancy outcome and can also improve our understanding of this fascinating insect.”

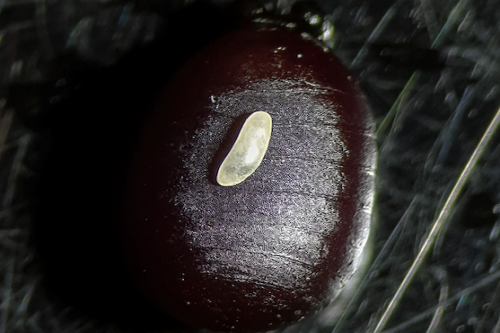

Lee Haines, Honorary Fellow at LSTM and Associate Professor at the University of Notre Dame, added: “This work brought new meaning to looking for a needle in a haystack. Sifting through tsetse poo in search of prematurely expelled eggs may not sound like a rewarding endeavour, but with the help of a microscope, we discovered these eggs could be reliably counted and their frequency could be linked to the age of tsetse mothers. This is something that is impossible to do in natural tsetse habitats.

“Being able to finally visualise and compare the size difference between an egg and a full-sized pupa was astounding when you realise that egg must develop into a full-term baby in just ten days. Think about that – from baby to full adult in ten days! It’s unfathomable!”

This study builds on previous research measuring how tsetse offspring health is influenced by their mothers’ age: July: Tsetse fly study | News and features | University of Bristol, and is also presented in the mini-documentary entitled Burrowing for Knowledge.

The study was funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) and the Royal Society.