University of Oxford: Nanopore technology achieves breakthrough in protein variant detection

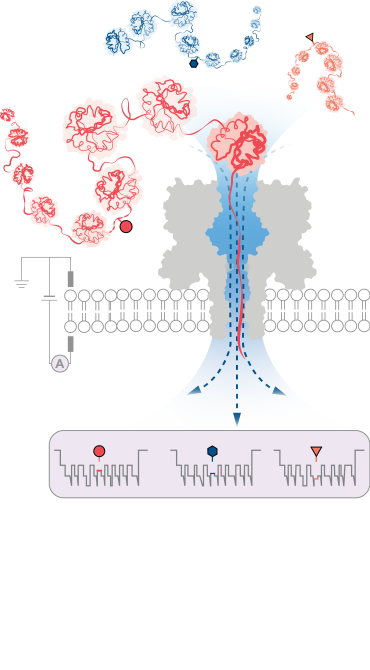

A team of scientists led by the University of Oxford have achieved a significant breakthrough in detecting modifications on protein structures. The method, published in Nature Nanotechnology, employs innovative nanopore technology to identify structural variations at the single-molecule level, even deep within long protein chains.

Human cells contain approximately 20,000 protein-encoding genes. However, the actual number of proteins observed in cells is far greater, with over 1,000,000 different structures known. These variants are generated through a process known as post-translational modification (PTM), which occurs after a protein has been transcribed from DNA. PTM introduces structural changes such as the addition of chemical groups or carbohydrate chains to the individual amino acids that make up proteins. This results in hundreds of possible variations for the same protein chain.

These variants play pivotal roles in biology, by enabling precise regulation of complex biological processes within individual cells. Mapping this variation would uncover a wealth of valuable information that could revolutionise our understanding of cellular functions. But to date, the ability to produce comprehensive protein inventories has remained an elusive goal.

The team successfully demonstrated the method’s effectiveness in detecting three different PTM modifications (phosphorylation, glutathionylation, and glycosylation) at the single-molecule level for protein chains over 1,200 residues long. These included modifications deep within the protein’s sequence. Importantly, the method does not require the use of labels, enzymes or additional reagents.

According to the research team, the new protein characterisation method could be readily integrated into existing portable nanopore sequencing devices to enable researchers to rapidly build protein inventories of single cells and tissues. This could facilitate point-of-care diagnostics, enabling the personalized detection of specific protein variants associated with diseases including cancer and neurodegenerative disorders.

Professor Yujia Qing (Department of Chemistry, University of Oxford), contributing author for the study, said: ‘This simple yet powerful method opens up numerous possibilities. Initially, it allows for the examination of individual proteins, such as those involved in specific diseases. In the longer term, the method holds the potential to create extended inventories of protein variants within cells, unlocking deeper insights into cellular processes and disease mechanisms.’

Professor Hagan Bayley (Department of Chemistry, University of Oxford), contributing author added: ‘The ability to pinpoint and identify post-translational modifications and other protein variations at the single-molecule level holds immense promise for advancing our understanding of cellular functions and molecular interactions. It may also open new avenues for personalised medicine, diagnostics, and therapeutic interventions.’

The study ‘Enzyme-less nanopore detection of post-translational modifications within long polypeptides’ has been published in Nature Nanotechnology.

This work was carried out in collaboration with the research group of mechanobiologist Sergi Garcia-Maynes at King’s College London and the Francis Crick Institute.

Video to illustrate how nanopore sensing works, based on Oxford Nanopore Technologies products for DNA/RNA sequencing. A double stranded DNA molecule is unwound and fed through a nanopore that is only wide enough for one base to pass through. The different bases are identified by measuring changes in an electrical current applied across the nanopore. This new research development opens the possibility that in the future a similar sensing platform could potentially be adapted for protein analysis. Credit: Oxford Nanopore Technologies, August 2023.