University of Tokyo Leading the Way in Transforming Reality Through Virtual Technologies

From attending a meeting to enjoying a live performance or, perhaps, taking a class at the University of Tokyo’s Metaverse School of Engineering, the application of virtual reality is expanding in our daily lives. Earlier this year, virtual reality technologies garnered attention as tech giants, including Meta and Apple, unveiled new VR/AR (virtual reality/augmented reality) headsets. We spoke with VR and AR specialist Takuji Narumi, an associate professor at the Graduate School of Information Science and Technology, to learn about his latest research and what VR’s future has to offer.

At the Avatar Robot Café DAWN ver. β, employees serve customers via a digital screen and engage in conversation using avatars of their choice, such as an alpaca and a man with blue hair.

Using avatars to bring out latent abilities

In the world of virtual reality, you can be anything you want in the form of a digital avatar, your alter ego. You can be taller, younger, a different gender or even a nonhuman creature. What’s more, such digital representations also alter your physical and cognitive abilities.

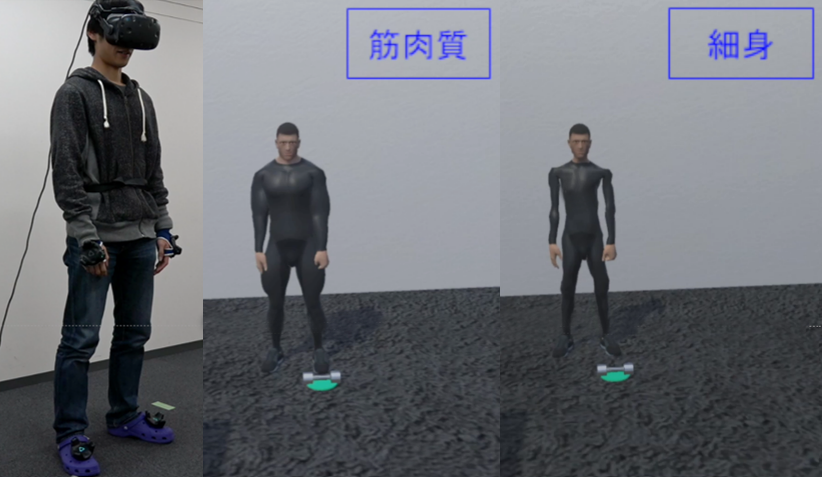

Take, for example, a muscular avatar. When a person dons a head-mounted display and enters the digital realm inhabiting the body of this avatar, their perceived weight of a dumbbell changes and feels lighter, whereas choosing a skinny avatar would make it feel much heavier. Associate Professor Takuji Narumi at the Graduate School of Information Science and Technology, who conducted the study, said this is due to a change in the way the person uses muscle unconsciously, which affects their perception of the weight. Another study of his also showed that people can even acquire nonhuman abilities. When people represent themselves as powerfully built dragon avatars, their spatial abilities are enhanced, enabling them to fly with more precision than when they use human avatars. Their fear of heights also diminishes, sweating less when standing in a high place. There is also a study conducted by researchers outside Japan that suggested improvement in people’s cognitive performance when employing an avatar of Albert Einstein, the renowned physicist.

“We are changing our behavior based on the way we perceive ourselves, unconsciously placing a limit on our abilities,” said Narumi, who is one of the leading virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) researchers in Japan. “But studies have suggested we can take off the shackles and bring out abilities by using virtual bodies that look different from us in the real world.”

Dubbed “ghost engineering,” with “ghost” referring to the function of the human mind that arises from the body, Narumi is on a quest to delve deeper and explore the possibility of creating a society where people can employ different avatars depending on the abilities they wish to boost. What if people use an avatar that can enhance their creativity at a meeting or use one that could help them loosen up and go wild at a party? With the use of avatars, there could be a future where people might be able to change a part of themself they thought could never change. Narumi believes such VR experiences could also help users gain new perspectives or improve relationships with others in the real world.

“My ultimate aim is to ease people’s minds. I want to create a society where people can acknowledge each other’s differences and be able to execute their abilities to the fullest,” he said.

Understanding how humans perceive the world and how they behave

Narumi’s interest in VR stems from his desire to understand the mechanisms of humans. Having grown up with a younger brother who is autistic, Narumi said he often wondered why other people had difficulty communicating with his brother when he never did. Upon realizing it was due to their shared experience of growing up together, he became curious about the way human mechanisms work. “To understand that, I wanted to create something that can be experienced rather than learning from textbooks,” he said. And for that, VR was a great tool.

“Even though the world of VR looks different from the real world, people believe it’s real, unable to distinguish what’s real from what’s not,” Narumi said. “But then, what’s ‘real’? What allows us to perceive our world? How are our senses created? I believe studying VR leads to finding out the answers and understanding human beings.”

After joining a lab led by Michitaka Hirose, then a professor at the Graduate School of Information Science and Technology (now emeritus professor and affiliated with the Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology), who is a pioneer in the field of VR research in Japan, Narumi has worked on various VR and AR projects. Among them was developing a system involving a “meta cookie,” a plain butter cookie whose taste changes into other flavors by altering its looks and smell by using a special head-mounted display. Narumi also developed a fake mirror that tweaks people’s facial expressions to make them look a bit happier or sadder. Named “incendiary reflection,” the study showed that looking at their smiling faces reflected in the mirror lifted the subjects’ spirits while sad faces evoked gloomy feelings.

“Humans have various senses, including sight and touch, and they’re bundled together in our bodies,” Narumi explained. “When you change the way we perceive through our senses, it also changes the way our body feels. And how your body feels is connected to even higher-level functions, such as emotions and cognitive skills.”

The “meta cookie” system consists of a device that emits scents and a head-mounted display that overlays images of cookies. The taste of a plain butter cookie changes to chocolate, strawberry or other flavors, depending on the scent and the image. Called the cross-modal effect, human senses interact in the brain and change the users’ gustatory sense.

Using a monitor that tweaks people’s facial expressions, the study showed that the subjects’ spirits lifted when looking at their smiling faces reflected in the mirror, while their sad face evoked gloomy feelings. Dubbed “incendiary reflection,” the research received Japan’s Good Design Award in 2013.

Changing reality and beyond

As an extension of his previous research on the human senses and emotions, Narumi currently studies ghost engineering. Although studies have suggested that we can modify our abilities to conform to our virtual self, people have expressed doubts about whether they want to carry over this phenomenon to the real world and apply it in their everyday lives to boost performance.

According to reports students submitted after listening to Narumi’s lecture on ghost engineering, many said they were hesitant of using the technology even if it became available in the future. The hesitation had to do with a sense of guilt for “deceiving” others by using avatars to do things well or to be accepted by society. The feelings stemmed from the gap between what they considered as their true self and their digital persona, or their belief that personality or ability is something that should be acquired through one’s efforts, and that’s what makes these attributes significant.

So, how can people come to accept themselves transformed by using avatars? To find out, Narumi has been studying the psychological transformation of people who work at Avatar Robot Café DAWN ver. β. There, the employees who have difficulty going out due to various circumstances wait tables by remotely controlling robots named OriHime. They feel at ease interacting with people by using the robots that all look alike, regardless of the “pilot’s” physical characteristics. Narumi explained that by having the same appearance also helps employees regard each other as equals, regardless of their social status, physical appearance or abilities. Such experiences could also lead to new insights, he explained.

In a related experiment, those who had been freed from their “individuality” are asked to serve customers via a digital screen as avatars of their choice — some choose to present themselves as alpacas while others decide to go as themselves. Narumi plans to follow this group over a long period to trace changes in their feelings or in the way they want to express themselves using avatars. With this research, Narumi hopes to identify the requirements for attaining a better life or for gaining a deeper understanding of oneself by using avatars.

In the long term, Narumi hopes to find out how the experience of temporal transformation in the world of VR could be incorporated into our lives in the physical world. So far, studies have shown people can edit their so-called minimal self, or the way they perceive themselves at a given moment, by using avatars. But can we also edit our narrative self, which is our long-term personal identity, including past memories and self-awareness?

“What’s the relationship between the minimal self and narrative self? Can we also edit the narrative self if we use VR that can influence the minimal self? I’m very much interested in finding out the answers to these questions,” Narumi said. “It would be amazing if we can develop technologies that would enable us, for example, to adopt the identities of our choice or to look back at the end of our lives and say, ‘It was a good life.’”