Unveiling Earth’s Biodiversity Evolution: Landscape Dynamics Hold Key Insights

Movement of rivers, mountains, oceans and sediment nutrients at the geological timescale are the central drivers of Earth’s biodiversity, new research published today in Nature has revealed.

The research also shows that biodiversity evolves at similar rates to the pace of plate tectonics, the slow geological processes that drive the shape of continents, mountains and oceans.

“That is a rate incomparably slower than the current rates of extinction caused by human activity,” said lead author Dr Tristan Salles from the School of Geosciences.

The research looks back over 500 million years of Earth’s history to the period just after the Cambrian explosion of life, which established the main species types of modern life.

Dr Salles said: “Earth’s surface is the living skin of our planet. Over geological time, this surface evolves with rivers fragmenting the landscape into an environmentally diverse range of habitats.

“However, these rivers not only carve canyons and form valleys, but play the role of Earth’s circulatory system as the main conduits for nutrient and sediment transfer from sources (mountains) to sinks (oceans).

“While modern science has a growing understanding of global biodiversity, we tend to view this through the prism of narrow expertise,” Dr Salles said. “This is like looking inside a house from just one window and thinking we understand its architecture.

“Our model connects physical, chemical and biological systems over half a billion years in five-million-year chunks at a resolution of five kilometres. This gives an unprecedented understanding of what has driven the shape and timing of species diversity,” he said.

The discovery in 1994 of the ancient Wollemi pine species in a secluded valley in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney gives us a glimpse into the holistic role that time, geology, hydrology, climate and genetics play in biodiversity and species survival.

The idea that landscapes play a role in the trajectory of life on Earth can be traced back to German naturalist and polymath Alexander von Humboldt. His work inspired Charles Darwin and Alfred Wallace, who were the first to note that animal species boundaries correspond to landscape discontinuities and gradients.

Water and sediment flux

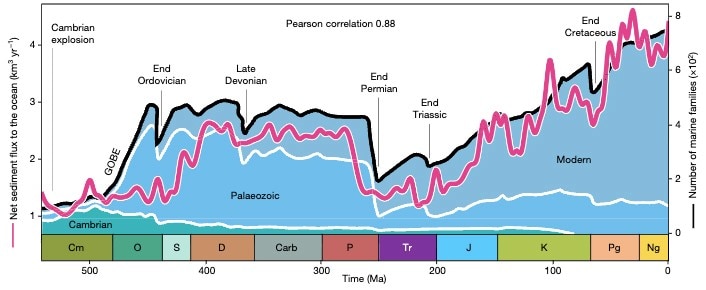

Researchers mapped how rivers drove sediment into the oceans over a 540 million year period.

“Fast forwarding nearly 200 years, our understanding of how the diversity of marine and terrestrial life was assembled over the past 540 million years is still emerging,” University of Sydney PhD student Beatriz Hadler Boggiani said.

“Biodiversity patterns are well identified from the fossil record and genetic studies. Yet, many aspects of this evolution remain enigmatic, such as the 100 million years delay between the expansion of plants on continents and the rapid diversification of marine life.”

In groundbreaking research a team of scientists – from the University of Sydney, ISTerre at the French state research organisation CNRS and the University of Grenoble Alpes in France – has proposed a unified theory that connects the evolution of life in the marine and terrestrial realms to sediment pulses controlled by past landscapes.

“Because the evolution of the Earth’s surface is set by the interplay between the geosphere and the atmosphere, it records their cumulative interactions and should, therefore, provide the context for biodiversity to evolve,” said Dr Laurent Husson from University of Grenoble Alpes.

Instead of considering isolated pieces of the environmental puzzle independently, the team developed a model that combines them and simulates at high resolution the compounding effect of these forces.

“It is through calibration of this physical memory etched in the Earth’s skin with genetics, fossils, climate, hydrology and tectonics by which we have investigated our hypothesis,” Dr Salles said.

Using open-source scientific code published by the team in Science in March, the detailed simulation was calibrated using modern information about landscape elevations, erosion rates, major river waters and the geological transport of sediment (known as sediment flux).

This allowed the team to evaluate their predictions over 500 million years using a combination of geochemical proxies and testing different tectonic and climatic reconstructions. The geoscientists then compared the predicted sediment pulses to the evolution of life in both the marine and terrestrial realms obtained from a compilation of paleontological data.

“In a nutshell, we reconstructed Earth landforms over the Phanerozoic era, which started 540 million years ago, and looked at the correlations between the evolving river networks, sediment transfers and known distribution of marine and plant families,” University of Grenoble PhD student Manon Lorcery said.

When comparing predicted sediment flux into the oceans with marine biodiversity, the analysis shows a strong, positive correlation.

On land, the authors designed a model integrating sediment cover and landscape variability to describe the capacity of the landscape to host diverse species. Here again, they found a striking correlation between their proxy and plant diversification for the past 450 million years.

In his 1864 novel A Journey to the Centre of the Earth, Jules Verne attributes this to his fictitious hero, Professor Otto Lidenbrock:

“Animal life existed upon the Earth only in the secondary period, when a sediment of soil had been deposited by the rivers and taken the place of the incandescent rocks of the primitive period.”

Dr Salles said: “This observation by Professor Lidenbrock to his nephew Axel fits strikingly well with our hypothesis. So, it should be no surprise that Jules Verne was greatly inspired by Humboldt’s work.”