Kroeber Hall, honoring anthropologist who symbolizes exclusion, is unnamed

UC Berkeley’s Kroeber Hall today became the fourth building on campus to be stripped of its name in a year’s time. The decision by Berkeley officials capped a formal review process and was made, in large part, because the building’s namesake — Alfred Louis Kroeber, born in 1876 and the founder of the study of anthropology in the American West — is a powerful symbol that continues to evoke exclusion and erasure for Native Americans.

A proposal to unname the hall was received in July 2020 by Chancellor Carol Christ’s Building Name Review Committee. The committee reached a unanimous vote last fall in support of removing the name, following an analysis of the proposal and a solicitation and review of comments from the campus community. Of the 595 responses received, 85% favored unnaming Kroeber Hall, home of the Department of Anthropology, Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum of Anthropology, Department of Art Practice and Worth Ryder Art Gallery.

Christ supported the decision, then sought and received necessary approval from UC President Michael Drake.

In her letter to Drake, Christ added that some of Kroeber’s views and writings “clearly stand in opposition to our university’s values of inclusion and our belief in promoting diversity and excellence.” She added that removing Kroeber’s name would “help Berkeley recognize a challenging part of our history, while better supporting the diversity of today’s academic community.”

Among the key reasons highlighted in the proposal and in the review committee’s recommendation to Christ was that Kroeber collected or authorized the collection of the remains of Native American ancestors and curated a repository of them for study. While the research practice was not illegal then, the review committee wrote, “it was immoral and unethical, even for the time.”

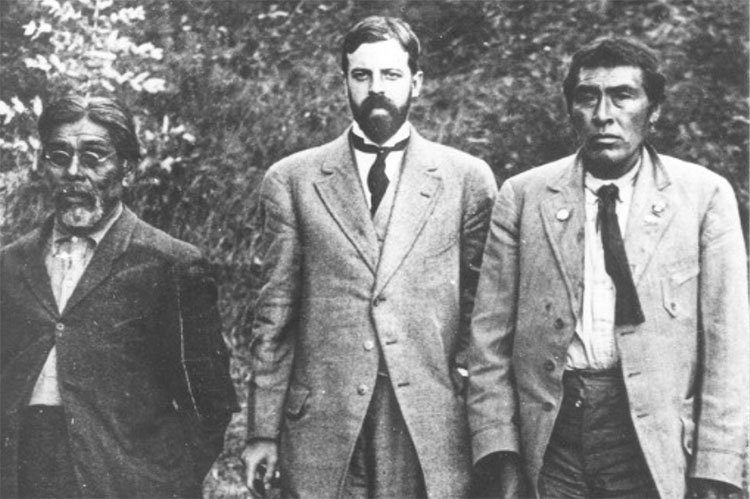

In 1911, Kroeber also took custody of a Native American man, a genocide survivor he named Ishi, and allowed him to live at the UC’s anthropology museum, where the proposal states that he ‘”performed’ as a living exhibit for museum visitors,” making Native crafts, such a stone tools. After dying of tuberculosis in 1916, his body was autopsied, against the wishes he’d expressed to Kroeber for cremation and burial without autopsy.

A campus announcement on Tuesday, Jan. 26, that Kroeber Hall had been unnamed was followed by metal lettering spelling the hall’s name being removed from the exterior walls. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

Additionally, Kroeber’s pronouncement that the Ohlone people were culturally extinct contributed to the federal government not recognizing the Ohlone and “leading to the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe having no land and no political power,” according to the committee.

Phenocia Bauerle, a member of the Apsáalooke tribe of Native Americans who is director of Native American student development at Berkeley and is on the campus’s Native American Advisory Council, said today’s announcement “may seem like just political correctness, just a gesture, but it is a big gesture, because, for so long, names like Kroeber were untouchable. He signified a particular version of history, and if Berkeley is willing to make room for other histories, different experiences, to be brought into the fold, this will allow societal change to happen.”

Ataya Cesspooch, a third-year Ph.D. student in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management, is Northern Ute, Assiniboine and Lakota. She is studying the complex and contradictory relationships between oil and gas development, environmental justice and tribal sovereignty on her reservation in northeastern Utah. Cesspooch also is coordinator of the American Indian Graduate Student Association and a member of the vice chancellor for equity and inclusion’s Native American Advisory Council. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

Removing Kroeber’s name, added Ataya Cesspooch, a Berkeley Ph.D. student who is Northern Ute, Assiniboine and Lakota, is a “first step” that Berkeley must take to acknowledge that “influential scholars, such as Kroeber, participated in the dehumanization of Native Americans.”

Boalt Hall, at Berkeley Law, had its name removed in January 2020, and last November, Barrows and LeConte halls also were unnamed on the same day. Like Kroeber Hall, each had a controversial namesake whose legacy clashes with Berkeley’s mission and values. Kroeber Hall will temporarily be called the Anthropology and Art Practice Building.

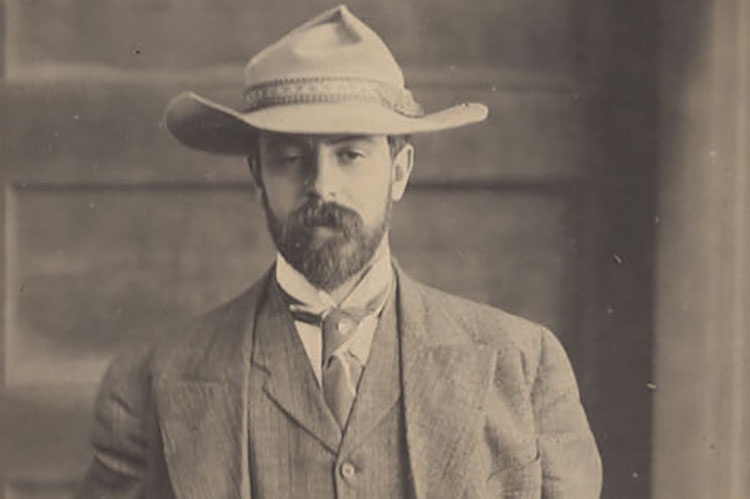

In 1901, Alfred Kroeber, shown here in 1907, began his more than 40-year career at the UC’s Department of Anthropology. The founder of the study of anthropology in the American West, he also was director from 1909-1946 of the university’s anthropology museum. (BANC PIC 1978.128, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

Founder of anthropology in the West

Alfred Louis Kroeber, raised in New York City, attended Columbia University, earning a B.A. in 1896 and an M.A. in 1897, both in English literature. At Columbia, he also met anthropologist Franz Boas, in Boas’ seminar on American Indian languages, and “was so affected by the encounter that he went on to obtain his anthropology doctorate in 1901, the first supervised by Boas at Columbia,” wrote Ira Jacknis, a Berkeley research anthropologist at the Hearst museum and a leading historian on Kroeber’s work, in Theory in Social and Cultural Anthropology: An Encyclopedia.

After getting his Ph.D., Kroeber moved to the San Francisco Bay Area, where the University of California was initiating a department and museum of anthropology. He was hired and began teaching anthropology in 1901, when he was 25, became a full professor in 1919 and retired in 1946. From 1909 to 1947, he also directed the University of California Museum of Anthropology — today the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum of Anthropology. Originally in San Francisco, the museum moved to Berkeley in 1931.

In 1911 in San Francisco, anthropologist Alfred Kroeber (center) is photographed near the UC Museum of Anthropology with Yahi translator Sam Batwai (left) and a Native American man named Ishi (right). (UCSF History Collection, UC San Francisco, Library, University Archives)

Along with Boas, Kroeber was a pioneer of American anthropology and one of the leading anthropologists of his generation. The author of more than 500 publications, he was a co-founder and president of the American Anthropological Association, presided over the American Folklore Society and founded the Linguistic Society of America.

The most important shift that Boas and Kroeber made in the discipline, said Jacknis, “is that they opposed theories of unilinear evolutionism, which were fundamentally racist because they arranged all cultures according to a presumed universal hierarchy, with white Euro-Americans at the top. Instead, they believed in cultural relativity, which was based on fieldwork, in which the anthropologist would travel to Native communities and interview them about their own cultures.”

Anthropologists Alfred and Theodora Kroeber sit on the steps of a cabin around 1927. They traveled together to many of Alfred Kroeber’s field sites. Theodora Kroeber, Kroeber’s second wife and a Berkeley alumna, wrote the book “Ishi in Two Worlds.” (BANC PIC 1978.128, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

Kroeber also was an innovator in the use of the wax cylinder machine to make ethnographic recordings of Native Californian languages and music.

“I think that is among his greatest achievements … no one else had done this up to that time,” said Jacknis, in an interview. “That led to his recordings of Ishi, which have become the only sound recordings of the extinct Yahi language.” These recordings became the foundation for the Breath of Life workshops, jointly held every two years by the Department of Linguistics and Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival and attended by Native scholars wishing to learn their ancestral, and often endangered, languages.

To Kroeber, “artifacts were secondary to linguistic notes and texts (folklore),” wrote Jacknis, adding that an examination of Kroeber’s fieldwork revealed that he spent relatively little time collecting.

Most of Kroeber’s fieldwork was in California, where he and his students began in 1903 a systematic survey of Native Californian cultures; this work was summarized in 1925 in Kroeber’s Handbook of the Indians of California, which founded the scholarly study of Native Californians.

Kroeber mentored at least two generations of anthropology students. With Thomas Waterman, one of his former students who became a Berkeley linguistics instructor, he wrote the first, and for many years the only, textbook in the field: Anthropology, first published in 1923. Kroeber died in 1960.

Unnaming Kroeber Hall “is a step toward recognizing the harm to Native communities that individuals, but also different (academic) disciplines, have had on Native communities,” said Phenocia Bauerle, director of Native American student development at Berkeley and a member of the Apsáalooke tribe. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

A controversial legacy

Kroeber’s legacy in Native California “was immense,” said Jacknis, “but controversial,” as shown in the proposal to unname Kroeber Hall and in the hundreds of comments that supported it.

That proposal proved controversial, too, as several faculty members argued in their comments — whether they ultimately supported or rejected the unnaming — that it was incomplete and unjust to Alfred Kroeber. For example, they said Kroeber engaged in few, if any, archaeological excavations in California and instead focused on ethnological research. They added that the museum was a repository for ancestral remains prior to Kroeber’s arrival, and that Kroeber actually curbed the UC’s major emphasis on California archaeology.

They stressed Kroeber’s pioneering fieldwork — often done through interviews with tribal elders — that helped salvage, after the American genocide, much about the history and culture of Native Californian tribes.

But Berkeley professor Paul Fine, chair of the Building Name Review Committee, said that the committee’s overarching resolve to recommend unnaming Kroeber Hall “was less about passing judgment on Alfred Kroeber and more about the university forging better relationships with Native Americans.”

“The reason many of us voted the way we did was because we really believe that the university is about today and the future,” he said. “And if we’re serious about being a welcoming place, being inclusive, we have to start acknowledging that the history of the UC, and the whole state of California, with its Native California inhabitants, has been awful since Day One, and relationships are still poor.

“What was powerful to me were the letters from Native American student groups and Bay Area tribes saying, ‘Hey, this is what Kroeber means to us.’”

A member of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band, one of the Ohlone tribes, Alexii Sigona is a second-year Ph.D. student in the Department of Environmental Policy, Science and Management and a member of the American Indian Graduate Student Association. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

Charles Hirschkind, chair of the Department of Anthropology, said he and many faculty members “think it is better that the name is not there. The name binds the discipline to a past that it no longer needs, and that doesn’t mean it’s not important to study Kroeber. But at the same time, there is no need to make monuments of those foundational figures whose contributions we recognize, but also whose flaws we can see more clearly now, from the standpoint of the present.”

Cesspooch, a third-year Ph.D. student in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management and, like Bauerle, a member of the campus’s Native American Advisory Council, said she supported the proposal to unname Kroeber Hall because “influential scholars, like Kroeber, participated in the dehumanization of Native Americans, and it’s important not to gloss over that or its impact on us today.”

Added Bauerle, “Kroeber wasn’t the sole actor in the California genocide, but he definitely played a part in the process that alienated California Indians, and he created a hierarchy of who were real Indians and who weren’t. His actions weren’t malicious, but they were flawed. Unnaming acknowledges that there was harm done.”

Cheyenne Two Feathers Tex, a media studies major who is minoring in journalism, is a member of the Northfork Rancheria of Mono Indians of California. She also is founder and co-director of RAW Media Now, a BIQTPOC magazine at Berkeley. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

And unnaming Kroeber Hall isn’t enough, said Fine, adding that the building sits on the unceded land of the Chochenyo-speaking Ohlone.

“It’s a good first step, but there needs to be real action,” he said. “The campus needs to commit resources to righting these wrongs and to think about the legacy of UC’s land and where it came from.”

On campus, “we need to do more than recognize that racism has happened by lifting up communities that were harmed,” added Bauerle, “and by coming to terms with the reality that the history of the university hasn’t always been shiny and bright.”