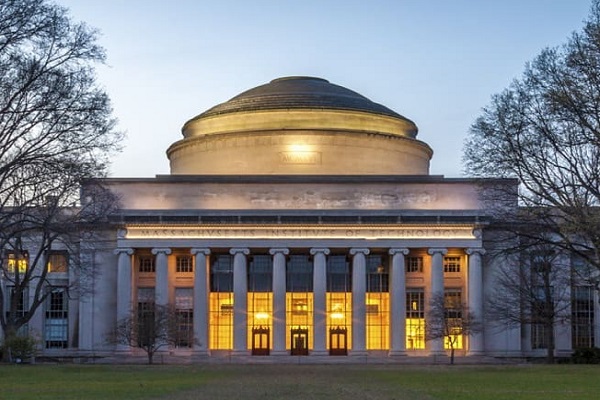

Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Making the case for “fake lawyering”

Most people wouldn’t put the words “MIT” and “lawyer” in the same sentence. In fact, only 1,393 alumni — about 1 percent — are lawyers, according to the MIT Alumni Association. But a contingent of MIT undergraduates is steadily earning a reputation for its prowess in “fake lawyering.” That’s how head coach Brian Pilchik describes the premise of the MIT Mock Trial program, which consists of a group of about 30 students that competes against other colleges around the United States in simulated courtroom trials. Each season culminates in the spring with a national competition run by the American Mock Trial Association (AMTA) — a sort of mock trial “March Madness” where roughly 600 teams vie for the coveted championship title.

This year, for the first time since the program’s inception, the MIT A team went undefeated in the AMTA regional tournament. MIT A was also the only team all year that beat Harvard University, which went on to win the national title. In addition, MIT advanced two teams, MIT A and B, to the second round of the competition, the national championship qualifier in New York — another first for the program. And the students won 12 awards for their individual performances as attorneys and witnesses — the most MIT has ever snagged at the AMTA competition.

“I was completely blown away,” says Pilchik, a co-founder of the team who is a trial attorney at the Public Defender Division of the Committee for Public Counsel Services. “I don’t think I could have anticipated that starting a brand new program in 2015 — and going through an entire pandemic with them and not being able to practice in a way we wanted to — that coming out of that we would be stronger than ever.”

Learning to litigate

In the fall, AMTA releases a fictional criminal or civil case that college mock trial teams work on throughout the year, always set in a mythical 51st U.S. state called Midlands. The cases are lengthy and detailed, with made-up witness affidavits, text messages, photos, and other relevant materials. “It’s really fun,” says Diego Colín, a senior and physics major who is co-president of MIT Mock Trial. “It’s like a big logic puzzle that’s 200 pages long that you have to dissect with your teammates, and you get into really heated arguments about these people that don’t exist.”

This year, AMTA crafted a criminal case: Chuggie’s Bar in Midlands burns down and the defendant — who owns the bar — is charged with aggravated arson. The prosecution’s theory is that the financially strapped owner torched Chuggie’s to collect the insurance money. The defense has some flexibility in how to proceed; they can argue, for example, that it was an electrical fire or that someone else set it.

The students practiced for at least two hours at each twice-weekly practice — and invested many more hours on their own — to prepare for roles as attorneys or witnesses. Pilchik and two MIT Mock Trial alumni coaches, Lia Hsu-Rodriguez ’21 and Zachary Bogorad ’19, helped them analyze the case and work on everything from objections, crosses, and redirects to vocal intonation, body language, and where to stand in the courtroom.

Throughout the fall, the program fielded teams at about a dozen college mock trial competitions around the country. These tournaments are intense; typically, each team competes in four trials, which last about three hours each. Real-life attorneys and judges preside over the trials, awarding votes (called ballots) to the winning teams.

Acting the part

“Mock trial is time-consuming, but it’s a journey that’s absolutely worth it,” says Colín. “It allows you skill-wise to become a standout, in the way you engage in public speaking and in arguments in general. It teaches you how to argue, not only to get your points out there, but to do it persuasively.”

Claire Southard, a first-year student who plans to major in computation and cognition, agrees. And joining the mock trial community has paid off in another way: It helped her adjust to MIT last fall, when she felt utterly uprooted from her home in Missouri. “It is so tight-knit, but in a way that’s so very welcoming to outside people to come join that community. I instantly felt like I belonged. I always left our practices in a better mood, even if something stressful was going on with school,” Southard says.

For those with an interest in theater, Mock Trial provides an opportunity to act in multiple roles; a typical case has a dozen or so witnesses. The AMTA affidavits provide some inkling of their characters, but there’s room for creative license. “The backstory is normally very much up to the student, so that can be kind of fun to come up with a persona for yourself that fits in with the facts of the case,” explains junior Emily Tess, a business management major and MIT Mock Trial co-president. For one of the witnesses she portrayed this year, she took inspiration from the character Mona Lisa Vito in the movie “My Cousin Vinny,” speaking with a thick Brooklyn accent, chomping on gum, and gesticulating liberally.

“The thing that is so special about mock trial is that, although it involves law and people always think about the attorney side, it’s also 50 percent witnessing — acting,” says Pilchik. Mock Trial offers students who are already actors, or want to try acting, an alternative to joining a student drama group or the Theater Arts program.

Fake lawyering, MIT style

The Mock Trial program’s trajectory from a fledgling program seven years ago to a serious competitor among schools that perform at the highest level — such as Tufts, Harvard, and Stanford universities, and the University of California at Los Angeles — has caught people’s attention, Tess says. “We’re really building a name for ourselves in this national community, and people are starting to recognize us for being successful.” She’s noticed that MIT is no longer being cast as an underdog in the mock trial podcasts she listens to.

Part of that success may lie in the particular strengths MIT students bring to the table — or the fake courtroom, as it were. Over the years, Pilchik has observed two areas in which they excel. One is their grasp of the rules of evidence, which restrict evidence that attorneys can bring forward. The rules are numbered, and students have to memorize all of them and cite them to object in the trial. “I’ve taught objections at lots of schools, and MIT students are very good at understanding how these restrictions and pieces of logic fit together,” he says.

Another is absorbing complex vocabulary, and technical or scientific concepts, which students playing expert witnesses need to be able to explain during a trial. “If we’re in a round against another school, and an MIT student has an opportunity to get up in front of a whiteboard and show that the other student is missing something or wrong about the math, that’s always fun!” Pilchik says.

Given their recent, unprecedented success in the AMTA tournament, Pilchik and the students are bullish about the future of MIT’s Mock Trial program. In addition to the teams’ stellar performances and taking home a slew of individual awards, beating Harvard this year was a sort of public bellwether, as well as the “internal validation our program needs,” says Colín.

“We have a lot of accumulated knowledge across all of our members, and that’s never going to leave as long as we keep getting new people and they are mentored by our leaders. Our knowledge base is only going to keep growing, and our baseline for how new members start is going to keep getting higher and higher. So I can’t picture us going down from where we are. We can only go up.”