European Commission fines Teva and Cephalon €60.5 million for delaying entry of cheaper generic medicine

The European Commission has fined the pharmaceutical companies Teva and Cephalon €60.5 million for agreeing to delay for several years the market entry of a cheaper generic version of Cephalon’s drug for sleep disorders, modafinil, after Cephalon’s main patents had expired. The agreement was concluded well before Cephalon became a subsidiary of Teva. The agreement violated EU antitrust rules and caused substantial harm to EU patients and healthcare systems by keeping prices high for modafinil.

Executive Vice-President Margrethe Vestager, in charge of competition policy, said: “It is illegal if pharmaceutical companies agree to buy-off competition and keep cheaper medicines out of the market. Even when their agreements are in the form of patent settlements or other seemingly normal commercial transactions. Teva’s and Cephalon’s pay-for-delay agreement harmed patients and national health systems, depriving them of more affordable medicines.”

Modafinil is a medicine used for the treatment of excessive daytime sleepiness associated in particular with narcolepsy. It was Cephalon’s best-selling product under the brand name “Provigil” and for years accounted for more than 40% of Cephalon’s worldwide turnover. While the main patents protecting modafinil had expired in Europe by 2005, Cephalon still held some secondary patents related to the pharmaceutical composition of modafinil, which aimed at securing additional patent protection.

Today’s decision concerns a patent settlement agreement whereby Cephalon induced Teva not to enter the market with a cheaper version of modafinil, in exchange for a package of commercial side-deals that were beneficial to Teva and some cash payments. Teva held its own patents relating to modafinil’s production process, was ready to enter the modafinil market with its own generic version, and it had even started selling its generic in the UK. Then, it agreed with Cephalon to stop its market entry and not to challenge Cephalon’s patents.

The Commission investigation has found that for several years, this “pay-for-delay” agreement eliminated Teva as a competitor and allowed Cephalon to continue charging high prices even if the main modafinil patent had long expired.

While generally patent settlements can be legitimate, we believe that the settlement agreement between Teva and Cephalon was not. Teva committed to stay out of the modafinil markets, not because it was convinced of the strength of Cephalon’s patents, but because of the substantial value transferred to it by Cephalon. The value transfer was mainly embedded in a number of commercial side-deals, which Teva would not have achieved without committing to staying out of the market.

Harm caused by pay-for-delay agreements

The delay in Teva’s entry, the most advanced generic competitor at the time of the settlement agreement, meant that Cephalon did not face competition from cheaper medicines. Without the “pay-for-delay” settlement agreement, Teva could have entered the market earlier and could have, in turn, pushed down prices for modafinil.

Generic entry brings price competition to markets that can lead to price drops of up to 90%. When Teva entered the UK market for a short period in 2005, it indeed offered a 50% lower price than the price of Cephalon’s Provigil.

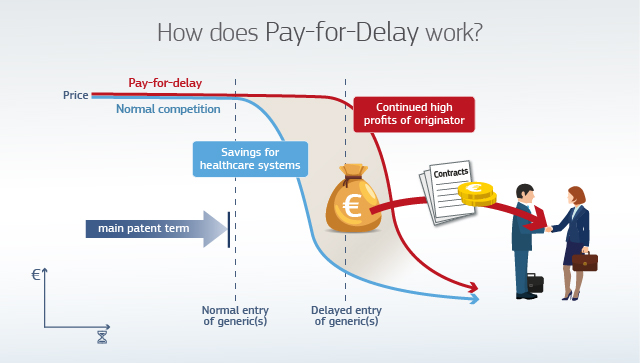

The graphic below illustrates the negative impact of pay-for-delay settlement agreements for patients and healthcare systems. Delayed generic entry prevents consumers and health systems from benefitting from significantly lower prices earlier. With pay-for-delay settlement agreements, companies share the extra profits generated by the lack of competition.

Pay-for-delay agreements can also have a detrimental effect on innovation. Competition from generics stimulates pharmaceutical companies to focus their efforts on developing new drugs rather than on maximising income streams from their old drugs by artificially preserving market exclusivity.

Fines

The fines were set on the basis of the Commission’s 2006 Guidelines on fines (see press release and MEMO). Regarding the level of the fines, the Commission took into account, in particular, the duration of the infringement and its gravity.

As in other “pay-for-delay” cases, the general fines methodology does not work for generic companies, as they, by virtue of the restrictive agreement, do not realise any sales with the affected product. The Commission, therefore, imposed a fixed amount fine to Teva that is slightly below the fine for Cephalon.

The fines imposed by the Commission on Teva and Cephalon are €30 million and €30.5 million, respectively, amounting in total to €60.5 million.

The infringement lasted, for almost all EU Member States and EEA countries, from December 2005 to October 2011, when Teva acquired Cephalon and they became part of the same group.

Fines imposed on companies found in breach of EU antitrust rules are paid into the general EU budget. This money is not earmarked for particular expenses, but Member States’ contributions to the EU budget for the following year are reduced accordingly. The fines therefore help to finance the EU and reduce the burden for taxpayers.