Massachusetts Institute of Technology research shows effects of admissions lottery on children

Attending preschool at age 4 makes children significantly more likely to go to college, according to an empirical study led by an MIT economist.

The study examines children who attended public preschools in Boston from 1997 to 2003. It finds that among students of similar backgrounds, attendance at a public preschool raised “on-time” college enrollment — starting right after high school — by 8.3 percentage points, an 18 percent increase. There was also a 5.4 percentage point increase in college attendance at any time.

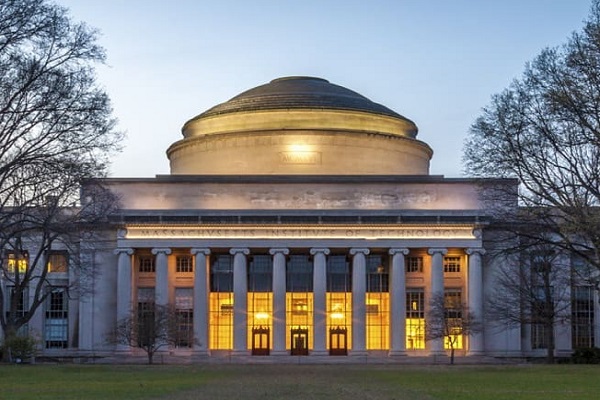

“We find that 4-year-olds who were randomly allocated a seat in a public Boston preschool during this time period, 1997 to 2003, are more likely to attend college, and that it’s a pretty large effect,” says Parag Pathak, a professor in MIT’s Department of Economics and co-author of a newly published paper detailing the study’s results. “They’re also more likely to graduate from high school, and they’re more likely to take the SAT.”

The study does not find a connection between preschool attendance and higher scores for students on Massachusetts’ standardized tests. But it does find that children who attended preschool had fewer behavioral issues later on, including fewer suspensions, less absenteeism, and fewer legal-system problems.

“There are many things that influence whether you go to college, and these behavioral outcomes are relevant to that,” says Pathak, who is also a director of Blueprint Labs, an MIT research center that uses advanced empirical methods to examine issues in education, health care, and the workforce.

The paper, “The Long-Term Effects of Universal Preschool in Boston,” is published in the February issue of the Quarterly Journal of Economics. The authors are Guthrie Gray-Lobe, a research associate at the Becker-Friedman Institute for Economics at the University of Chicago and a research affiliate at MIT’s Blueprint Labs; Pathak, who is the Class of 1922 Professor of Economics at MIT; and Christopher Walters PhD ’13, an associate professor of economics at the University of California at Berkeley.

Lottery numbers

Publicly funded preschool programs have become increasingly popular and prevalent in recent decades. Across the U.S., 44 states operated publicly funded preschool programs as of 2019, along with 24 of the 40 biggest U.S. cities. The portion of 4-year-olds in the U.S. in a public preschool program has grown from 14 percent in 2002 to 34 percent in 2019.

To conduct the study, the researchers followed the academic trajectories of over 4,000 students, in seven cohorts from 1997 to 2003, who took part in a lottery the Boston public school system conducted to place students into a limited number of available preschool slots.

The use of the lottery makes the study rigorous: It creates a natural experiment, allowing the researchers to track the educational outcomes of two groups of students from otherwise similar backgrounds in the same school system. In this case, one group attended preschool, while the other did not. That approach has rarely been applied to studies of preschool programs.

“The [method] of this work is to take advantage of the elaborate rationing that happens in big-city school districts in their choice processes. We’ve developed techniques to find the right treatment and control comparisons in data produced by these systems,” Pathak says.

The study also found a 5.9 percentage point jump in attendance at four-year colleges for students who had attended preschool. Preschool-educated students also were 8.5 percentage points more likely to take the SAT.

“It’s fairly rare to find school-based interventions that have effects of this magnitude,” says Pathak, who won the 2018 John Bates Clark medal, awarded annually by the American Economic Association to the best economist under age 40 in the U.S.

But while the study does find that preschool increases SAT scores, there was no discernible change on the MCAS, the standardized tests Massachusetts students take in multiple fields in elementary school, middle school, and high school. That stands in contrast to the larger link in education between higher test scores and college attendance.

“It’s not the case that we have an increase in test scores and it corresponds with an increase in college-going,” Pathak says. “That’s very intriguing.” At the same time, he adds, “I don’t think the takeaway here is we shouldn’t have people take tests.”

On their best behavior?

Indeed, the study’s findings suggest that preschool may have a long-term beneficial effect that is not strictly or even primarily academic, but has an important behavioral component. Children attending preschool may be gaining important behavioral habits that keep them out of trouble. For instance: Attending preschool lowers juvenile incarceration by 1 percentage point.

“If I had to speculate what’s behind these long-term effects for college, this is our leading hypothesis,” Pathak says of the reduction in behavioral problems. “There’s a lot more that needs to be done on this. It’s an intriguing finding. Others have highlighted these sorts of so-called noncognitive sleeper effects of education, and I’ve been quite skeptical about it. But now our own findings suggest there may be something to that story.”

Experts in the field say the study is an important addition to the literature on the subject.

“I am really excited by this work,” says Christina Weiland, an associate professor in the School of Education and the Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan, who has spent 16 years studying the Boston public preschool system. “We’re seeing the really positive long-term effects of attending preschool.”

Weiland’s own long-term research begins with students who entered the preschool system a few years after the current study ends, beginning in 2007 — when the Boston Public Schools made substantial improvements to their preschool curriculum and pedagogy — and have themselves now entered college and the work force. One aim of her work is to evaluate how different types of preschool experiences influence students.

“A really important question is not only whether preschool works, yes or no, but how, and what kind of preschool,” Weiland adds. “Preschool programs can range quite a bit in terms of what skills they are emphasizing and the type of curriculum they’re using, and we’ve gotten some signal that some of those approaches in the shorter term produce better results than others. But we need to follow them, as Parag’s team did, to figure out what the longer-term effects are for different models.”

While academic research about preschool programs dates at least to the 1960s, the current study has a distinctive set of attributes and findings, including the use of the Boston lottery to create a natural experiment; the long-range nature of the effects being found; and the combination of minimal impact on test scores coupled with indications that preschool has lasting behavioral benefits.

“There are probably two broader lessons,” Pathak says. “We cannot judge the effectiveness of early childhood interventions by just looking at short-run outcomes, stopping by third grade. You’d get a totally misleading picture of Boston’s program if you did that. The second is that I think it’s really critical to measure outcomes beyond test scores, such as these behavioral outcomes, to have a more complete picture of what’s happening to the child.”

Shedding more light on the subject is possible, Pathak thinks, by further analyzing preschool programs with policies that create natural experiments.

“We’re really excited because there’s a lot of potential to apply our approach to other settings,” Pathak says.

The study was supported, in part, by the W.T. Grant Early Career Scholars Program, while the Boston Public Schools and Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education helped facilitate the research.