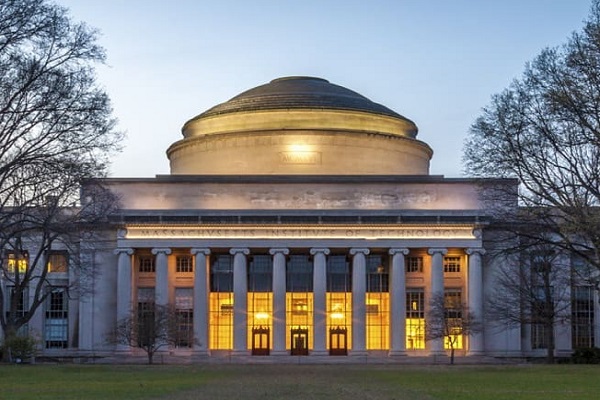

Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Study finds an unexpected upside to workplace impostor thoughts

Even many successful people harbor what is commonly called impostor syndrome, a sense of being secretly unworthy and not as capable as others think. First posited by pyschologists in 1978, it is often assumed to be a debilitating problem.

But research by an MIT scholar suggests this is not universally true. In workplace settings, at least, those harboring impostor thoughts tend to compensate for their perceived shortcomings by being good team players with strong social skills, and are often recognized as such by their employers.

“People who have workplace impostor thoughts become more other-oriented as a result of having these thoughts,” says Basima Tewfik, an assistant professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management and author of a new paper detailing her findings. “As they become more other-oriented, they get evaluated as being higher in interpersonal effectiveness.” Importantly, across her studies, she does not find that this interpersonal upside comes at the expense of performance.

Tewfik’s research as a whole suggests we should rethink some of our assumptions about impostor thoughts and their dynamics. For example, “the idea that having these thoughts at work is always going to be bad for you may not be entirely true,” she observes. At the same time, she emphasizes, the prevalence of these types of thoughts among workers should not be ignored, dismissed, or even encouraged, given that she also finds that impostor thoughts lower self-esteem.

“There are far better ways to make someone interpersonally effective that may not come with well-being downsides,” says Tewfik, who is the Class of 1943 Career Development Professor at Sloan, and whose research often examines workplace and organization issues.

The paper, “The Impostor Phenomenon Revisited: Examining the Relationship between Workplace Impostor Thoughts and Interpersonal Effectiveness at Work,” is available online from the Academy of Management Journal and will appear in the June print edition.

Observations from the field

The concept of the “Impostor Phenomenon” was originally put forth in a 1978 paper by two psychologists, Pauline Rose Clance and Suzanne A. Imes, who initially focused their work on women with high-achieving careers and kept exploring the subject in subsequent work.

Even that original conceptualization observed that people suffering from the impostor phenomenon are often very socially skilled, an overlooked aspect of the issue that Tewfik decided to explore in greater detail. Her research includes fieldwork in firms, as well as experiments, to pinpoint the consequences of what she terms “workplace impostor thoughts,” both in causal and correlational terms.

For instance, Tewfik surveyed employees at an investment management firm, to see which of them harbored workplace impostor thoughts, while collecting employee evaluations from their supervisors. Those employees with more impostor-type thoughts were seen by their employers as working more effectively with their colleagues, with no drawbacks on their productivity overall.

“I did find this positive relationship,” Tewfik says. “For those having impostor thoughts at [the beginning of the time period], two months later their supervisors rated them as more interpersonally effective.”

Tewfik then examined a physician-training program and repeated the process of surveying trainees who were honing their skills through practice interactions with patients. Similarly, those who more frequently reported workplace impostor thoughts were the ones who connected best with patients.

“What I found is again this positive relationship, those physicians in training [with more impostor thoughts] were rated by their patients as more interpersonally effective, they were more empathetic, they listened better, and they elicited information well,” Tewfik notes.

Because the physician-training program featured recorded videos of the physician-patient interactions, Tewfik was able to pinpoint how some physicians connected better with people: “Those physicians in training who reported more impostor thoughts were also the ones who exhibited greater eye gaze, more open hand gestures, and more nodding, and this essentially explains why patients were giving them higher interpersonal effectiveness ratings.”

Tewfik also conducted two additional experiments, using the Prolific platform, with employees across a range of industries, to establish that the effects were causal. Specifically, she randomly assigned participants to two groups, finding that those harboring impostor thoughts were again more other-oriented, in asking more questions during the experiments, which led them to receive higher interpersonal effectiveness ratings from hiring managers.

Rethinking a real problem

These convergent field work and experimental results, Tewfik thinks, establish a clear chain of causality related to impostor thoughts, in which workers deploy compensatory mechanisms to thrive despite them: “Because you’re having impostor thoughts, you’re adopting an other-focused orientation, which is leading you to be more interpersonally effective.”

The data also suggest that workplace impostor thoughts are not a permanent feature of an employee’s mentality; people can shed those kinds of concerns as they become more established in their positions.

In general, Tewfik thinks, such dynamics indicate that workplace impostor thoughts “may not be what we’ve have originally conceptualized,” at least in the popularized form. Indeed, Tewfik prefers not to refer to workplace impostor thoughts as a full-fledged syndrome, with its connotations of negativity and permanence.

Even so, she adds, “What I don’t want people to take away is the idea that because people with impostor thoughts are more interpersonally effective, it’s not a problem.” People working in nongroup settings may struggle with the same thoughts but have no way of compensating for them through interpersonal connections because of their solitary work routines.

“I found a positive net outcome, but there might be scenarios where you don’t find that,” Tewfik says. “If you’re working somewhere where you don’t have interpersonal interaction, it might be pretty bad if you have impostor thoughts.”

Tewfik is continuing her own research on the subject, examining issues like whether workplace impostor thoughts might be tied to other important workplace outcomes like creativity and proactivity. She says she would be glad if more scholars establish additional empirical conclusions about workplace impostor thoughts.

“I hope this paper will spur a broader conversation around this phenomenon,” Tewfik says. “My hope is really that other scholars join this conversation. It’s an area that is ripe for a lot of future research.”