Ultraviolet ‘television’ for animals helps us better understand them

University of Queensland scientists have developed an ultraviolet ‘television’ display designed to help researchers better understand how animals see the world.

Until now, standard monitors on devices like televisions or computer screens have been used to display visual stimuli in animal vision studies, but none have been able to test ultraviolet vision – the ability to see wavelengths of light shorter than 400 nanometres.

Dr Samuel Powell from the Queensland Brain Institute‘s Marshall lab said this new technology will help unveil the secrets of sight in all sorts of animals, such as fish, birds and insects.

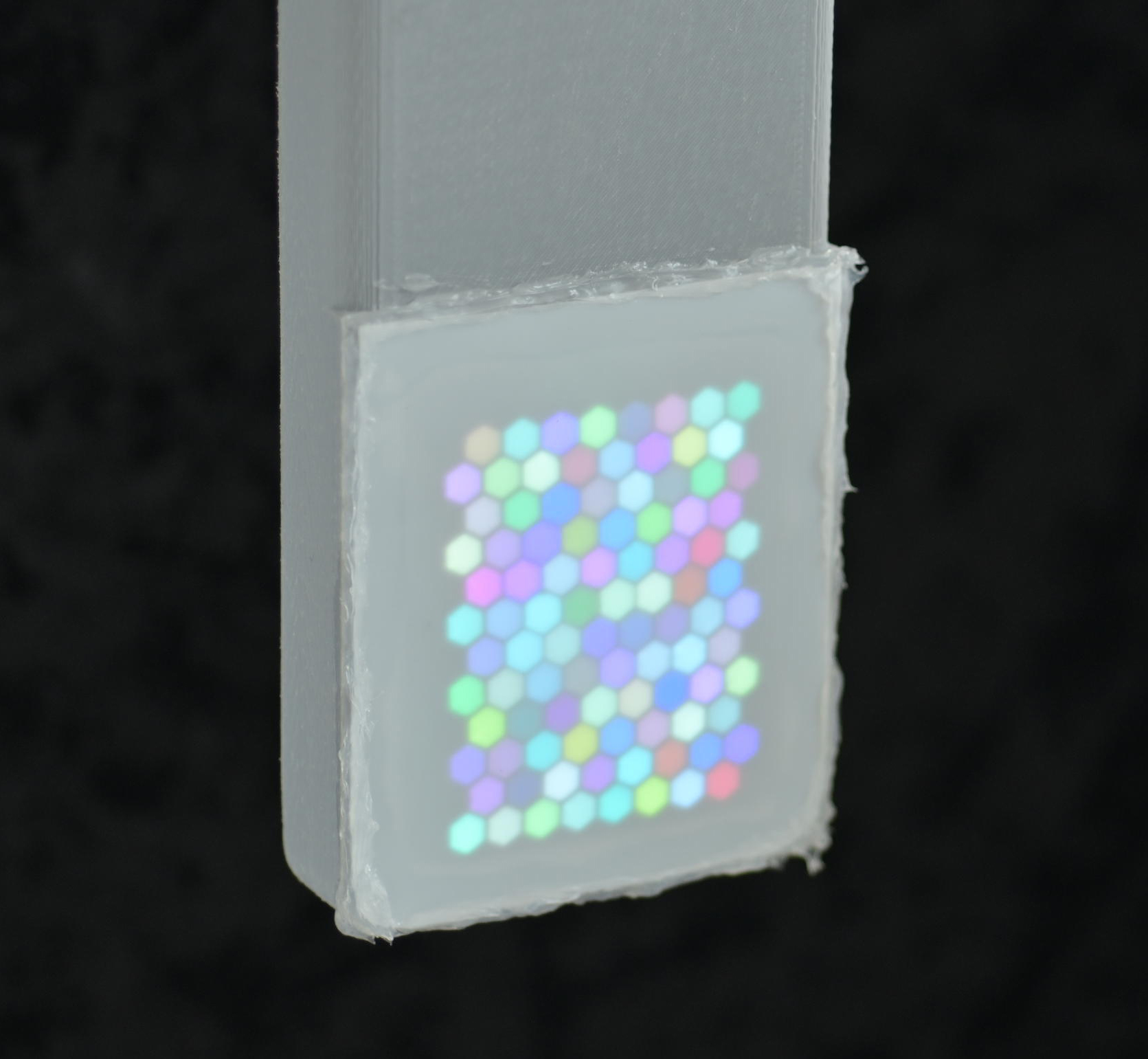

“Human TVs generally use three colours – red, green and blue – to create images, but our newly-developed displays have five, including violet and ultraviolet,” Dr Powell said.

“Using this display, it’s now possible to show animals simple shapes, to test their ability to tell colours apart, or their perception of motion by moving dot patterns.

“We affectionately call it the ‘UV-TV’, but I doubt that anyone would want one in their home!

“You’d have to wear sunglasses and sunscreen while watching it, and the resolution is quite low – 8 by 12 pixels in a 4 by 5 centimetre area – so don’t expect to be watching Netflix in ultraviolet anytime soon.

“You’d have to wear sunglasses and sunscreen while watching it, and the resolution is quite low – 8 by 12 pixels in a 4 by 5 centimetre area – so don’t expect to be watching Netflix in ultraviolet anytime soon.

“This very low resolution is enough to show dot patterns to test fish perception, in what’s known as an Ishihara test, which would be familiar to anyone who’s been tested for colour blindness.

“In this test, humans read a number hidden in a bunch of coloured dots, but as animals can’t read numbers back to us, they’re trained to peck the ‘odd dot’ out of a field of differently coloured dots.”

Dr Karen Cheney from UQ’s School of Biological Sciences said this technology will allow researchers to expand our understanding of animal biology.

“There are many colour patterns in nature that are invisible to us because we cannot detect UV,” Dr Cheney said.

“Bees use UV patterns on flowers to locate nectar, for example, and fish can recognise individuals using UV facial patterns.

“We’ve recently started studying the vision of anemonefish or clownfish – aka, Nemo – which, unlike humans, have UV-sensitive vision.

“Our research is already showing that the white stripes on anemonefish also reflect UV, so we think UV colour signals may be used to recognise each other and may be involved in signalling dominance within their social group.

“Who knows what other discoveries we can now make about how certain animals behave, interact and think.

“This technology is allowing us to understand how animals see the world, helping answer significant questions about animal behaviour.”

The research has been published in Methods in Ecology and Evolution (DOI: 10.1111/2041-210X.13555).

Image above left: The UQ-developed ultraviolet ‘television’ display is only 8 by 12 pixels in a 4 by 5 centimetre area – so don’t expect to be watching Netflix in ultraviolet anytime soon.

Video credit: Valerio Tettamanti